Last week, there was a moment that embodied for me an important (but often overlooked) part of our President's legacy. In the midst of delivering his farewell address, President Obama paused to thank his wife, Michelle, for her kind and courageous leadership during his presidency. “Michelle LaVaughn Robinson, girl of the south side, for the past twenty-five years you have not only been my wife and mother of my children, you have been my best friend,” he began, tears glistening in his eyes. “You took on a role you didn’t ask for," he continued, "and you made it your own with grace and with grit and with style.” Obama wept, and he wasn’t alone. I watched with tears streaming down my face — and it was in that moment that I realized just how much it has meant to me, as a man, to watch my president cry.

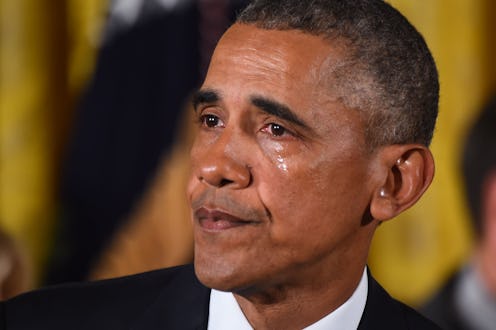

Meaningful as it was, this was far from the first time that Obama has wept during a public address. He teared up when thanking his campaign staff after winning in 2012. His eyes were moist when he spoke in the aftermath of Sandy Hook. And perhaps most memorably, Obama broke down last year while advocating for gun control. When he said, “Our inalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, those rights were stripped…from first graders in Newtown,” his soaring oratory was matched only by his emotional honesty. In that speech, Obama demonstrated exactly why crying should never be associated with being weak.

When the President of the United States weeps openly, it sends an unmistakable signal about what true power looks like. And it’s a signal that meant so very much to me as I grew into adulthood over the course of his presidency.

In childhood, I — like most men I’ve spoken with in my life — received the clear signal that repressing your emotions, particularly the painful ones, was part of what it meant to be a man. I actually had it better than many; I can remember seeing my father cry on several occasions, and holding back tears was never an expectation in my home. My minister frequently cried in the pulpit, to the point that it became a congregational inside joke.

I never lacked for positive male role models who had a healthy relationship with their emotions, and yet I still internalized the damaging cultural script that defines weeping as weakness, and bottling one’s emotions as strength. Iconic male characters, from John Wayne cowboys to Indiana Jones, were heroes in large part because they could suppress their feelings while everyone else went to pieces. On the playground, tears would prompt shame and ridicule. Vulnerability was associated with the feminine; expressing one's emotions could invite jeers of "sissy," "wuss," or just the classic reminder to "be a man."

I received the clear signal that repressing your emotions, particularly the painful ones, was part of what it meant to be a man.

Avoiding tears wasn’t the only tenet of this rigid masculinity. Growing up, I was a bookish kid who often got picked on — so when I got to college, I spent borderline-obsessive amounts of time in the gym attempting to bolster a more masculine image. I learned, as many men do, to climb male social hierarchies, finding ways to inflate my own social standing by exerting dominance over my peers. Sometimes this took the form of relatively innocuous behaviors, like intellectual posturing in the classroom; other times, it was more overt — like when I used to spray a bookish kid in my fraternity with a fire extinguisher.

Then, one day, I woke up and realized I was living in an emotional prison of my own making. I saw how my narrow masculine identity was damaging my relationships — with romantic partners surely, but also with my friends. It's hard to underestimate the alienation that comes with constantly suppressing one's true feelings. Perhaps more than anything, I realized how blunting my emotions damaged my ability to enjoy the best aspects of life: I was no longer able to feel deeply, and my aversion to being vulnerable diminished my capacity to love.

Slowly, I began to unlearn my own toxic masculinity. I reacquainted myself to my emotions, and tried to become more comfortable with expressing them. Starting out, this meant simply allowing myself to cry in private. I used to seek out YouTube videos that I hoped might stir and surface my neglected feelings.

Eventually, I graduated to being vulnerable around other people. However, it wasn’t, and isn’t, an easy process — unbinding years of acculturation rarely is. I still find myself, at times, repressing my own emotionality, shutting down instead of opening up; I’d be lying if I said I’ve entirely divorced myself from John Wayne-style masculinity.

However, with every step I take further away, I find I like the man I’m becoming a little bit more. And throughout this, it’s meant so much to have a president I can look to as a role model. The only childhood memories I have regarding President Clinton's masculinity largely feature blue dresses and cigars, and George W. Bush's good-ol'-boy charm — while less overtly predatory — didn't do much to redefine traditional masculinity.

Against this backdrop, it thrilled me to watch Obama dare to feel so openly. When discussing children who have been brutally and senselessly slain, tears are an appropriate response. In that context, stoicism is not a sign of strength, but an indicator of emotional damage. Crying is not inappropriate when thanking people who have volunteered countless hours to support your reelection. And the tears Obama shed in thanking Michelle mark a man who’s unafraid to be vulnerable in front of his partner. Obama’s emotional honesty holds the potential to transform masculinity from a social construct that prizes aggression and dominance to one that finds strength in emotional expression.

In light of this, it’s beyond painful for me to see Obama juxtaposed against the regressive masculinity of President-elect Trump. Whereas Obama demonstrates a healthier masculine ideal, Trump embodies masculinity at its toxic extreme, in his actions as well as his policies. His candidacy was marked by routine displays of dominance, acts of aggression, and a tendency to belittle those less powerful than himself. A man who's emotional range runs the gamut from "Sad!" to "Winning!", he denigrates women, victimizes the marginalized, and seems to take great pleasure in his own cruelty. In short, the Clinton campaign was on point in when comparing him to all the worst cinematic bullies.

I shudder to think what boys across the country may learn from him about what it means to be a man. On the heels of a leader who boldly stepped beyond traditional masculinity, we have elected a man who revels in the worst masculine impulses. I have no recourse but to weep.