Books

This New Essay Collection Is An Examination Of Body Image Like You've Never Read Before

“When Amye and I decided to solicit essays for My Body, My Words, we wanted it to be body inclusive, and reveal what it’s like to live with illness, as an overweight person, as an amputee, as a man, as a woman, as neither, as an addict, as a mom and dad,” says Loren Kleinman of the just-published collection she and fellow writer, Amye Barrese Archer, co-edited. “My Body, My Words is a survey of the body, showing insight into what it’s like to be.”

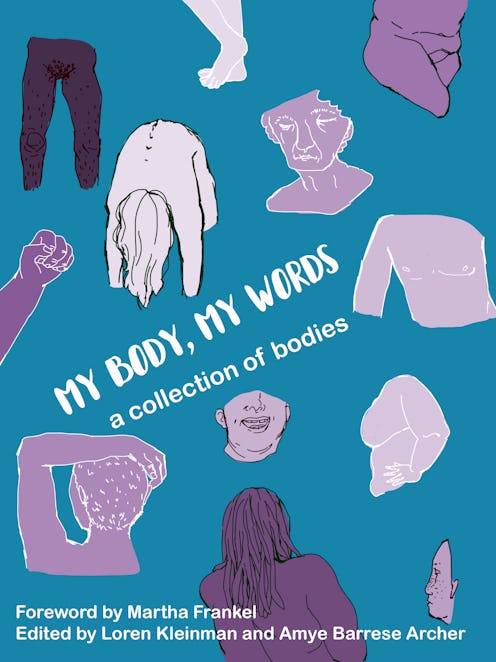

My Body, My Words: A Collection of Bodies Edited by Loren Leinman and Amye Barrese Archer, $17, Amazon

Out now from Big Table Publishing, My Body, My Words: A Collection of Bodies is an essay collection that features writers of every age and gender identity, every body size and shape and ability, who have grappled with everything from sexual assault and eating disorders to miscarriage and infertility, and so many other things a body can go through in a life — recognizing and honoring the weight, physical and metaphorical, that our bodies carry.

“I have been writing about my body for the last five years, but I’ve been struggling with it, thinking about it, warring with it for the last 30,” says Archer, sharing how her own experiences with body image informed her desire to put together the collection. “My memoir, Fat Girl, Skinny, dealt specifically with weight loss and body image, and when I was promoting that book and speaking to different groups, I began to realize how universal this issue was. When you are a fat person, you tend to think that only fat people fight this war, but I discovered the opposite. Women and men of all shapes and sizes related to my story and my struggle. I knew there were stories out there — we just had to find them.”

"When you are a fat person, you tend to think that only fat people fight this war, but I discovered the opposite. Women and men of all shapes and sizes related to my story and my struggle."

Archer says she was also inspired by her 11-year-old twin daughters. “I’m already seeing signs of body image struggles within them. I wanted them to see that not only is it okay to struggle with loving your body, but more importantly, that they are not alone in that struggle," she says. "And I wanted them to feel not-alone.”

Kleinman says her own childhood experience with illness informed how she’s understood her body throughout her life. She describes how her mother discovered a string of small lumps trailing down her neck when the writer was about eight-years-old, which resulted in months of tests, biopsies, and ultimately surgery in Sloan Kettering Memorial Hospital.

“At Sloan Kettering, I met many boys and girls who were struggling with various cancers,” the writer says. “My roommate, another 8-year-old, died while I was recovering from my surgery. I remember being so sad and in pain from the procedure. At 8-years-old, I became aware of the fragility. After I healed, the doctor’s incision left me with a thick, bumpy scar, about two inches in length across the side of my neck. I see this mark always, a reminder of the body’s mortal promise.”

"I remember being so sad and in pain from the procedure. At 8-years-old, I became aware of the fragility."

Readers will recognize a number of authors featured in My Body, My Words, including Beverly Donofrio — author of the New York Times bestselling memoir, Riding in Cars with Boys, and Ashely Nell Tipton — an advocate of full figured fashion for women and winner of Project Runway Season 14. Archer and Kleinman highlight others as well:

Riding in Cars with Boys by Beverly Donofrio, $12, Amazon

“We feel incredibly honored to be allowed entry into so many writers’ lives. Among the many vulnerable and authentic pieces, we loved Kathleen McKitty Harris’ piece, 'A Timeline of Human Female Development.' We fell in love with her essay on first read. We also loved Wynn Chapman’s 'The Fat Filly' and Jennifer Morgan’s 'Fifty to Eight Pounds of Shame.' Both stories deal with the shame, whether self-inflicted or embedded from those around them. These writers, like the other writers in the collection, are sharing the raw parts of themselves with readers.”

My Body, My Words: A Collection of Bodies Edited by Loren Leinman and Amye Barrese Archer, $17, Amazon

They’re also mindful to note that struggles with body image and the trauma and pain experienced by the body — as well as the strength and joy — are not experiences exclusive to women, or reserved for any gender in particular. Writers of all gender identities share their stories in the collection, including a number of cisgender men.

"These writers, like the other writers in the collection, are sharing the raw parts of themselves with readers.”

“We’ve had a cultural awakening regarding the fluidity of gender in this country,” the writers say. “And while we still may not be where many think we need to be in terms of equal civil liberties for all humans, we are at least having that conversation. In light of this, we felt it very important to include human stories, rather than strictly women’s stories.”

Kleinman says, “As a survivor of rape, I think we make a mistake when we claim trauma or pain as an experience only associated with gender. Pain is universal. Rape is universal. Violence is universal. Unfortunately, that silence is also the language of that pain, of that trauma. Telling our stories and listening is the start of that breaking off from silence, and entry into healing. If we don’t listen to one another then we say: 'what has happened to you did not happen.' If no one cares to listen, then we can never retaliate against the boundary our suffering has imposed on us.”

It's an idea she’s explored outside of My Body, My Words as well. In a recent essay, published in Ploughshares, Virginia Woolf and the Language of Trauma, Kleinman wrote of Woolf:

"She got me to listen to the larger story within myself, to recognize my pain. And today, we see the manifestation of that absence, that silence in movements such as #MeToo. As women and men tell their stories and audiences acknowledge their suffering. Through that acknowledgement, we empathize with them in the confusion, humiliation, wounds, terror, and struggles that have been lived through."

Both writers have their own ideas about what living in a more body positive culture looks like.

“I struggle with positivity, and I think the movement struggles with positivity, but that’s its beauty, its authenticity,” says Kleinman. “I will never be 100% positive about my body. That’s my humanity. I’ve grown to accept that uncertainty, that often-painful delicateness that comes with balancing perfection and reality. In an ideal world, everyone would love their body with overwhelming positivity, but then that wouldn’t be the truth. And I’d rather know the truth, whether overweight or thin, happy or sad, sick or healthy. My Body, My Words provides a glimpse into both the individual, private struggle with positivity and a more national conversation. If those individual stories aren’t told, then we have no evidence to show for a larger dialogue.”

"That’s my humanity. I’ve grown to accept that uncertainty, that often-painful delicateness that comes with balancing perfection and reality."

Included in My Body, My Words are a number of essays about where and whom we learn our ideal body image from, the displacement of not recognizing the body you see in the mirror with your image of yourself, misunderstandings and insensitivities from the medical establishment, and the myriad ways writers have learned to navigate the difference between inner-self and body.

“I want the fat jokes to not always be the easiest,” says Archer. “We have come so far in terms of microaggressions and cultural sensitivity, yet if you turn on the late night shows, the hosts often go for the fat joke when talking about public figures (who should be shamed on their merits — the policies they create and the words they say, not their weight). We have a President who fat shames women to the cheers of thousands of supporters. This is not okay. The reason I wrote Fat Girl, Skinny was because I believed and still believe that fat shaming is one of the last acceptable forms of ridicule and harassment in our culture. In that book, I detailed incidents where I was ridiculed by adult co-workers, boyfriends, and even strangers for being overweight. I wanted the world to know what a fat person lives like and lives through on a daily basis. I think that work has continued, yet expanded, in My Body, My Words. Many of the essays in the book deal with the social pressures of being “normal,” yet none of us seem to know what normal is. I think we need to approach body image much in the same way we approach gender and sexuality — as a private space.”

I ask the writers how My Body, My Words speaks to the recent surge in the #MeToo Movement and the founding of the Time’s Up legal defense fund. “While #MeToo has only recently come into the public discourse, it has been building silently and patiently inside the lives of women and men for generations,” says Archer. “We have been socially programmed to think we should fit into a certain box, but for many of us-that box never fit. This collection aims to give those box-less readers a home, a point of recognition.”

“We have been socially programmed to think we should fit into a certain box, but for many of us-that box never fit."

My Body, My Words adds even more critical stories and voices to the national conversation — offering readers the opportunity to explore the experiences of others struggling to feel safe in their bodies, challenged with body image and body positivity, and simply learning to navigate the world from inside their own, physical being.

“I think how men and women accept their bodies’ starts from the top,” Kleinman says. “Our models, including the American media, politicians, and businessmen and women promote excessive lifestyles filled with violence, power, and over the top sexuality. This extreme living has affected our bodies in ways that we are aware of and ways we are not. I realize that sexual abuse has been evident for years, but I think now more than ever, the narrative, as a result of social media use, is that any person can be reduced to ‘like.’ People are disposable and they’re for our viewing pleasure. Rather than be treated as human beings with thoughts, feelings, goals, bodies, we are either clickable or not, either f*ckable or not. I think the #MeToo narrative is challenging this notion, and bringing back personhood, personal stories. The consequence is that we return to a more stable, balanced place of remembrance, which is a return to our humanity. My Body, My Words is that return to humanity, to the body we call home, and its beautiful fragility.”