Books

Why It Took 'The Glass Eye' Author 10 Years To Write About Her Family Secret

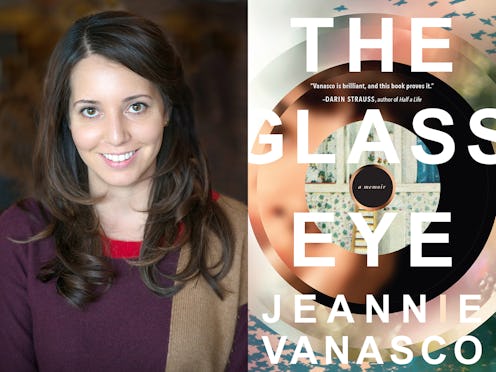

Jeannie Vanasco spent over ten years writing her debut memoir, The Glass Eye, published by Tin House Books earlier this fall; but readers wouldn’t guess it. Not because the memoir isn’t skillfully written and thoughtfully structured — it is — but rather because Vanasco’s deeply intimate story of loss, grief, and mental illness reads as though it happened just last week, yesterday, today. There’s a particular “nowness” to The Glass Eye: an in-the-moment immediacy that plants readers directly into Vanasco’s experience. That experience is the loss of Vanasco’s father when she was just 18-years-old, and the subsequent mania that threatened to take over her life.

But The Glass Eye navigates far more than the staggering loss of a parent. Readers discover that Jeannie’s father — her lifelong hero — named her after his daughter from a previous marriage — a daughter who died in a car accident at just 16-years-old. Discovering the truth about that other Jeanne (Vanasco’s half-sibling, without the ‘i’) becomes central to the writer’s own journey of self-discovery and healing.

Author Jeannie Vanasco connected with Bustle after The Glass Eye was published, to discuss her writing process, what it was like to research her own personal history, what insight her experiences with mental illness have given her on the current healthcare crisis in the United States, and so much more.

“As a reader, I’m not interested in a memoir’s synopsis. I’m interested in its author’s exploration of thoughts and feelings, thoughts about feelings, and feelings about thoughts. To me, that’s what makes a memoir feel alive,” says Vanasco, when asked what it was like to spend so many years in the throes of one manuscript. “For several years, my memoir was a tonally cold collection of scenes: this happened, then this happened. I didn’t reflect much on my thoughts and feelings. They were mentioned but not explored. After I started adding passages from my journals, that’s when the book’s meaning took hold. There’s a vulnerability to trying hard, and to making it known that you tried hard. I wanted the reader to feel that vulnerability.”

The night before her father passed away, the then-teenaged Vanasco promised him she would write a book for him. As readers will quickly discover, The Glass Eye is as much about Vanasco’s story as it is about Vanasco trying — and struggling — to write that story. It was a creative decision supported by Vanasco’s editor, Masie Cochran, who told her: “I think the book is about the struggle to write the book.” With that vision and insight, The Glass Eye really took off.

The Glass Eye by Jeannie Vanasco, $11, Amazon

“My best writing happens when I trust my instincts, when I go by ear or gut,” Vanasco says. “After the rough draft exists, I can let my brain unpack the meaning. The mistake I made with The Glass Eye: my brain moved in before the manuscript was ready for it. I drafted excessive outlines, imposed insignificant image patterns, almost as soon as I started the memoir. I tried to control the writing process, but that’s likely because I felt no control in my life, emotionally or mentally.”

It was important for Vanaco to include these details of her writing process in the book. “In memoir, I think it’s important to remind readers that they’re reading just one person’s interpretation of the story,” she says. “Reminding readers of the artifice reminds them that they’re reading a true story, or as true as the writer can make it. The most authentic thing I could do would be to show the lack of control — without sacrificing my authority as a narrator. My book’s structure asks the reader to do a little work.”

Vanasco’s research into her own life is compelling — which she conducts as though she were a biographer writing about someone else, not a memoirist outlining the rises and falls of her own life. She writes about being unable to trust her own medical records because she often lied to her doctors. She includes present-tense conversations with her mother, clarifying Vanasco’s own memories of her father. The details of her half-sibling Jeanne’s death shift depending on the source — and Vanasco often learns that her own recollections aren’t necessarily supported by fact.

“I feel so estranged from the research experience,” Vanasco says. “The best I remember, it aggravated my symptoms, landing me in the hospital a lot. The research that probably pushed me over: learning that shortly after I was born, my dad was holding me and pacing around the back yard, crying. He wouldn’t put me down. When my mom asked him what he was doing, he said: “It’s a hard day.” It must have been late May, my half-sister Jeanne’s birthday. She died in 1961. I was born in 1984. Hearing that story, that’s when I registered the extent of my dad’s ongoing grief.”

Many memoirists don’t go quite the distance Vanasco did — it’s clear from The Glass Eye that she often researched relentlessly. I asked her why getting the facts right, even when they directly conflicted with her own memories and experiences, was so important.

“As a memoirist, I felt it necessary to get the facts right, she says. “I’m not saying that I always did. That’d be impossible. But I tried. And I wanted to show myself trying. I really worry that nonfiction writers are exploiting the idea of Truth, embellishing facts because it makes the writing process easier. I prefer to treat facts as constraints. They push me into a deeper place, forcing me into corners I don’t want to be in. And finding ways out of those corners, that often makes for more interesting reflection.”

Vanasco writes about her episodes of mental illness in a way that makes them so accessible, almost seeming rational at times. During periods of mania, she connects sounds, images, events, and coincidences in ways that make sense — at least, right up until that moment they don’t. Often, her musings simply read like the mind of an overly-enthusiastic writer, rather than the compulsions of someone struggling with mental illness.

“I definitely do not want to pathologize the creative process,” she says. “Writing a book can be messy and difficult for even the most mentally stable individual. The process, as disorganized as it is, can look rational from the outside. For example, I sometimes used a tape recorder. It’s not absurd, as a writer, to use a tape recorder. But the reason I turned to a tape recorder: my thoughts moved faster than my typing; I’d been writing on my arms and legs and ran out of room. My process went too far. I stopped sleeping. I stopped eating. [But] it’s not weird to connect sounds, images, events, and coincidences; they make sense — ‘right up until the moment they don’t.’”

Throughout the memoir, Vanasco describes receiving care from a variety of free clinics and mental health facilities, at times with and without insurance. I ask if her experiences — both with access and lack thereof to different levels of care — have given her any perspective on the debate over the right to healthcare that is happening in the United States right now, and that has been ongoing for years.

“I think it’s essential that we not romanticize mental illness, and that we also remove the stigma surrounding public programs,” she says. “The Affordable Care Act lifted the stigma surrounding public health insurance. I no longer felt guilty using public benefits like Medicaid, Social Security Disability, and Medicare. Those programs provided me access to good treatment, and now I have a full-time job with benefits. If we don’t help one another, if we don’t acknowledge the country’s structural problems — a major reason why we need public benefits — we are not going to move forward in this country.”

She has a wealth of personal experience to back up her beliefs. “Off and on, in my early twenties, I accidentally took methadone,” Vanasco shares. “I feel pretty dumb admitting it. But I didn’t always have health insurance. I couldn’t afford my medications — and because I felt guilty being on Medicaid, which I needed because I couldn’t hold a full-time job that offered benefits — I turned to an online Canadian pharmacy, ordering what I thought was my prescribed medication. A few years later, when I ended up in the hospital for an overdose, the doctors found methadone in my system. I was so confused and embarrassed. But how was I supposed to know that I was taking methadone? In my teens and twenties, I hadn’t experienced consistent emotional or mental stability. I had no standard of comparison. I hadn’t had good treatment — because I didn’t have consistent health coverage.”

It’s because of this experience, and others, that Vanasco is so passionate about healthcare, and so concerned about the current administration’s steps towards dismantling the Affordable Care Act.

“A major conservative policy belief that infuriates me: deregulation of the pharmaceutical industry. Trump has been pushing to speed up, if not dismantle, the approval process for prescription drugs. Shortly after his inauguration, he told pharmaceutical executives [the administration will] ‘be cutting regulations at a level that nobody’s ever seen before, and we’re going to have tremendous protection for the people.’ At least ninety-seven percent of all drugs fail clinical trials. The approval process should not be treated as a nuisance. Drug companies should be required to prove their drugs work before the FDA legalizes them. However, provided the drugs pass the “safe” test, as in “won’t kill you,” they could be approved. But safe isn’t the same as effective. That’s why deregulation is a bad idea, and why public health insurance is a good idea.”

But, she says, she believes that reading and writing memoirs could actually help the country.

“At their core, they reveal what’s human about us. They allow us to inhabit a consciousness that’s not our own,” Vanasco says. “The good memoirs, at least — memoirs that are self-aware, not self-absorbed. The problem is, how do you get Americans to read good memoirs when we’re inundated with easy, mass-appeal entertainment? It requires a certain level of education and self-discipline to choose Speak, Memory over Game of Thrones, and it terrifies me, because mass entertainment is what got Trump elected.”

I ask Vanasco if she thinks writing was healing or enabling to her experiences of mania — and whether or not it can be both, if the risks outweigh the rewards.

“I didn’t know how to write about my dad’s death without reliving it, which in turn aggravated the mania and depression. Same thing with my psychotic episodes,” she says. “I won’t lie: I miss mania. I could write for several days straight without sleeping. I could go several days without eating. I felt passionate about topics ranging from nineteenth-century copyright law to the portrayal of black cats in Medieval literature. Once a reserved, insecure perfectionist, I lost track of how many men I’d slept with — and, for the first time, I enjoyed sex — however, one could argue that this was a numbers game; the more men I slept with, the more likely I would find one who was good at it. My mania felt phenomenal — to me, at least. But, in retrospect, my writing from those manic episodes was bad. I know it was bad. And I lost so many friendships, which only furthered my depression.”

But the overall message, again, turns to compassionate, comprehensive healthcare. “The goal is, I think, to find medication that doesn’t blunt one’s thoughts and feelings, but rather helps the individual feel more alive, more human. Thoughts and feelings don’t simply make good memoirs; they make us human.”