Books

In Elizabeth Strout’s Novels, The World Changes But People Stay The Same

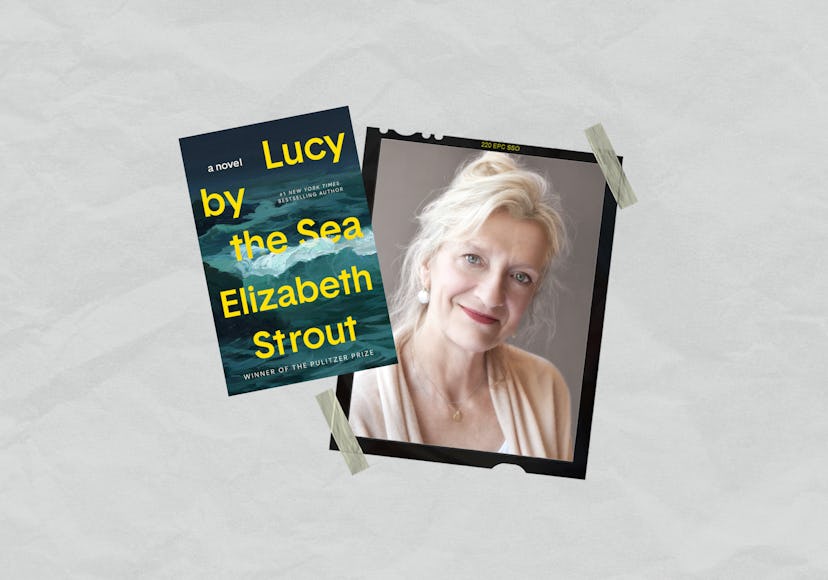

Strout’s latest book revisits Lucy Barton, a character the author has followed across four titles.

Readers first met Lucy Barton, the febrile, warm-hearted writer, in 2016’s My Name Is Lucy Barton. Back then, author Elizabeth Strout introduced us to a woman reflecting on her physically and emotionally impoverished childhood in Amgash, Illinois, while recovering from an operation in a hospital bed in New York. In the years since, Lucy has been the subject of occupied four of Strout’s last five books, including the newly released Lucy by the Sea, which traps Lucy again, this time on the coast of Maine during the first year of the pandemic, alongside her ex-husband and friend, William.

But while the world has changed, Lucy herself is has stayed the same: anxious, empathetic, and above all, observant. “I actually do think we're born with a certain nature, that we're not born a blank slate,” Strout tells Bustle. She adds, sounding almost sanguine, “We're just rolling on. We are who we are. Our faces change, our bodies change, our lives change, but we somehow don't.”

Unlike the nervous Lucy, who avoids difficult subjects, Strout is drawn to knotty, complicated topics and characters. Her first book, Amy and Isabelle, was published in 1998, when she was 42, but she gained more mainstream literary acclaim in 2008, when she won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for Olive Kitteridge. That book, a novel-in-stories about a difficult woman Strout describes as “like everybody on steroids,” was adapted into an HBO miniseries starring Frances McDormand in 2014. Now 66, Strout is one of the most prolific and lauded fiction writers working in America. To top it all off, her 2021 novel Oh William!, another book about Lucy, is currently shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

After she finished writing Oh William!, Strout turned her attention to the only story in the world: the COVID-19 pandemic. Though few novels have approached the subject so far, Strout felt that she couldn’t ignore such a momentous event, and set about documenting it. “I wasn’t sure that [the publishers] were going to put it out as fast as they did,” she confesses. “Because I thought, ‘Wait a minute, I’m not even sure people are reading books. I’m not sure they’re going to be ready.’” But the book is out, and Strout hopes that it will serve as a record of how the early months of pandemic made people feel: dislocated, anxious, and yearning for connection. “Hopefully someday,” she says, “maybe 10 years from now when somebody new hasn't gone [through it]; their memory of it isn't quite as…” She trails off. “[It’s] an act of faith.”

Below, Strout discusses writing about COVID-19, finding Lucy Barton’s voice, and searching for moments of connection.

I'm fascinated by the fact that you keep going back to these characters. How do you approach that? Do you have a plan, or if something like COVID-19 happens, do you think, "I wonder what they would be doing?”

So, I do seem to keep going back to my characters. I never plan to. But I think they become so real to me, as I'm working on them, that they just stay in my head. I had just finished Oh William! and then this started and I thought, “Oh, man. They’re there. Let’s have them go get stuck up on the coast of Maine together in this house on a cliff and see what happens.” So, it was really a combination of having them already very much still in my head.

And then the pandemic began, and all that uncertainty that we didn’t know what would happen. I mean, I didn’t know how I could be writing about anything else. If I had been working on a different book, I would probably have continued on that book. But the coincidence of ending Oh William! and then the pandemic occurring, I just had to go into it with them.

Were you concerned about writing about the pandemic?

I was, because like I said, I probably would've just continued on with a different book had I been writing one, but because this happened and because it was so important, I thought, “I have to try and get this down.” And one of the most difficult things for me about writing this book was the sense of time. Because time just... It imploded. There was no time anymore, especially that first year. Everything just globbed into one day or night or whatever, and that was so strange. And I really wanted to be able to get that down.

But at the same time, it's a novel, it needs to have some narrative thrust. So, I could find it because life has people, and when there's people, there's going to be things that happen no matter what. So, I managed to do that, but I was hoping to be able to capture that sense of weird time.

You also used a very conversational first-person style in this book, along with other books about Lucy, unlike in Olive Kitteridge, which is written in the third person. Why did that style feel right for Lucy?

When I first wrote My Name is Lucy Barton, that was the beginning of [this style]. And it came to me because I heard her voice. Usually, I just feel the presence of a character. And I realized, “I'm going to have to write this in her voice because that’s who she is.” And it was almost like a fine gold thread coming down in front of me. And as long as I could hold onto that thread, then I could have Lucy, because it’s her distinctive way of talking. And I was very nervous about writing from the first person because it’s a very different way to write a book. But I felt, because I had just finished Oh William!, that I could still probably access that thin gold thread and get her through this pandemic.

Part of what I find so gripping about your work is that sense of people seeing each other really deeply, or recognizing that someone else is seeing them. Often, these very subtle moments pass by quickly in real life. When did you become interested in writing about those moments?

I’m not really sure, but I do know that I have been interested in people my entire life. I mean, I don’t think there's anything more interesting than people and all the different permutations that we seem to manage to bring to ourselves and the world. And then, as I began to work on my adult work, I began to realize that there was a theme of attempts to connect. I’ve become more interested in that, even in my conscious, not-writing life. Trying. Failing, but trying, succeeding, failing again.

Usually, I intend to write about a person as honestly as I can. I learned this back with Olive Kitteridge, the original Olive Kitteridge. I remember I was writing that book, parts of it, in Provincetown, in a little cottage right on a beach. Just one little room on this beach, and I just wrote all day because I was younger and I had more energy and I had to get it done. And I remember standing at the end of the day and looking out at the beach and thinking, “She’s just too much to take.” And then, I remember thinking, “Let her be Olive.” And that was an enormous moment for me as a writer, not just for Olive, but because I realized, “No, no. Let them be who they are for better or worse. I’m not judging them. The readers can judge them, but let them be who they are.”

That was a really pivotal moment for me, to understand forever that I would allow whoever I was writing about to be who they are. And they are what we all are, which is complicated.

Another thing you do so well is write about shame. You had a fairly repressed, Puritanical upbringing. Did that affect your writing about shame?

Well, it probably [did], now that you mention it. That’s very interesting, I had never made that connection. But yes, probably that sense of growing up in a household culturally that never spoke of things, feelings or anything. And yet, I had nothing but feelings. My first husband was Jewish and that was an entirely different culture. It was so refreshing, because everybody talked about anything, and I was just amazed. So, that was eye-opening and wonderful. But only recently again have I recognized that I do have an ongoing theme of shame.

I’ve been thinking about it a little bit and I think that there’s, in my mind, a connection between remorse and shame, but they're not the same thing. They're actually quite different, but they touch each other. I don’t think that remorse is a bad thing. For example, Olive feels it. She feels it about her son. She recognizes at moments — “Look what I did.” And she feels remorse. And I don’t think that's a bad thing for people to feel because it’s real and it makes us human. But that's different from shame, which is just a continual blush that seems to come off Lucy's face. Every time she opens the door, she's blushing. I feel like, “The poor thing.”

Does writing about those feelings just happen naturally now?

I think at this point it just happens naturally. I think at this point I just keep going for the sentence that sounds the best for me. It's a very ear-oriented process of writing, because the sentence needs to land on the reader’s ear in the right way. And it needs to be a truthful sentence in every sense of the word. It took me years to learn what that meant.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.