News

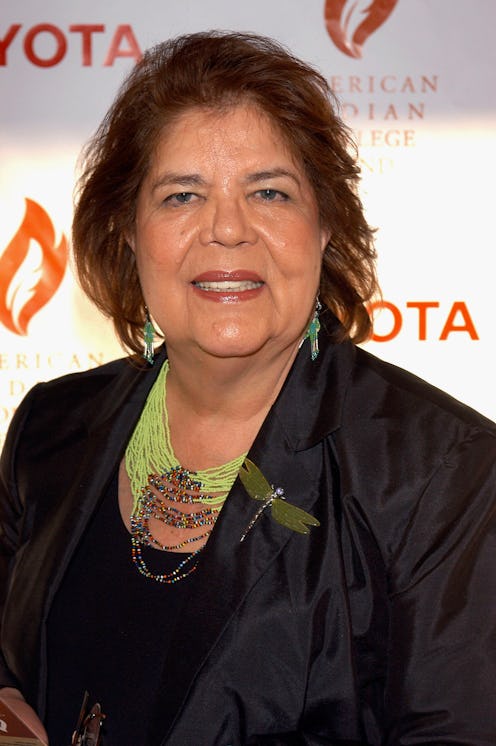

Who Was Wilma Mankiller?

The campaign to put a woman on the U.S. $20 bill has named its finalists: a group of women whose faces might grace an American banknote for the first time in history. When the nonprofit group “Women on 20s” tallied the 256,000 votes made through its website, four finalists emerged: former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, abolitionist Harriet Tubman, civil rights activist Rosa Parks, and Wilma Mankiller. Familiar with the first three, I stumbled over the last on the list. Who is Wilma Mankiller?

The first three women received 100,000 votes each, according to the organizers, but Mankiller reportedly made it onto the final ballot “by popular demand” and “strong public sentiment that people should have the choice of a Native American to replace Andrew Jackson.” Voting on the finalists is now open; once a winner is chosen, Women on 20s will approach the White House and the Treasury about putting her on the $20 bill. The group hopes to for approval by 2020, the centennial of U.S. women receiving the right to vote. If the initiative gets the go-ahead, it will be the first change to the all-male currency since 1929.

Wilma Mankiller, the first woman to be elected chief of a large native American tribe, died in 2010. Mankiller's New York Times obituary characterized her as tenacious, both in her personal and public life. She was chief of the Cherokee tribe from 1985 to 1995 and achieved significant success during her tenure. In her ten years in office, Mankiller reportedly rejuvenated the tribal government, improving education, health and housing in the process. She also focused on alternative energy and small business development. The Cherokee Nation’s membership nearly doubled during her term: from 68,000 to 170,000. It is currently the second largest tribe in the country, after the Navajo.

Mankiller was born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, in 1945, the sixth in a family of eleven children. Her father was full-blooded Cherokee, and her mother was Dutch-Irish by descent. When her family was moved to San Francisco as part of a relocation policy, she described the uprooting as “my own little Trail of Tears.” (The original Trail of Tears was the result of Andrew Jackson’s removal policy, which transplanted the Cherokee from east of the Mississippi to Oklahoma in 1838-9. Mankiller herself pointed out in a 1993 speech that it was actually President Jefferson who conceptualized the removal, but still, it would be a deliciously symbolic act were Mankiller to “remove” Jackson’s smug mug from the $20.)

She married in 1963 and had two daughters. After her marriage ended in 1977, she returned to Oklahoma. Once there, she began volunteering and found work as economic stimulus coordinator for the Cherokee Nation. She was awarded her social science bachelor’s from Flaming Rainbow University and began to do graduate coursework in community planning. She became director of the Cherokee community development department in 1981 and deputy chief of the Nation in 1983. She succeeded the former chief in 1985 and then won elections in 1987 and 1991.

Of this period of her life, she said:

I certainly didn't start to work there with an agenda to become Chief; there was no precedent for that. There'd never been a second Chief or a principal Chief who was female, but I came to the position with absolute faith and confidence in our own people and our own ability to solve our own problems, and I began developing programs that reflected that philosophy.

The role of chief requires one to be both cultural custodian and financial decision-maker. Mankiller invested much of the Cherokee Nation’s extensive budget ($150 million by the end of her period in office) in health care and job training, as well as education. During her tenure, she also managed to fit in some writing, penning the autobiography Mankiller: A Chief and Her People with Michael Wallis.

She eventually gave up the chieftainship in 1995 because of her declining health. Sickness was not a new experience for her: she had suffered from both lymphoma and myasthenia gravis (a neuromuscular disorder), as well as recovering from kidney failure. After leaving office she remained a major force in Cherokee politics and lectured as a guest professor at Dartmouth. In 1998, she was awarded the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, by President Bill Clinton.

Mankiller died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 64. At her death, the Cherokees’ principal chief said:

We are better people and a stronger tribal nation because of her example of Cherokee leadership, statesmanship, humility, grace, determination and decisiveness. … When we become disheartened, we will be inspired by remembering how Wilma proceeded undaunted through so many trials and tribulations.

The Women on 20s campaign is not the first major recognition Mankiller has received since her death. This year, Gale Anne Hurd, executive producer of The Walking Dead announced that she hoped to make a documentary, entitled Mankiller, about the life of the first female chief of the Cherokee. Hurd told Huffington Post blogger Michael Vasquez:

You might think the first woman to become principal chief of the Cherokee Nation is unrelated to my Sci-fi productions, but the late Wilma Mankiller was a real-life Ellen Ripley or Sarah Connor, and like the women of "The Walking Dead" she was a survivor-warrior who stepped up to lead her people.

Hurd highlighted Mankiller’s leadership skills, her success in uniting the Cherokee Nation, and the appalling removal of the narratives of “original Americans” from U.S. history books. Mankiller herself goes unmentioned in most history books, Hurd pointed out. “Honoring Wilma on the 100th anniversary of women's suffrage in 2020, could not be more perfect,” she said, in reference to the Women on 20s project.

Novelist Louise Erdrich clearly agrees. Writing in support of Mankiller in the New York Times opinion pages, she says:

In America, the most widely recognized Native American women are the ones who contribute to the national mythos (in story) by assisting white men in the business of taking Indian land — Pocahontas and Sacagawea. Wilma Mankiller was another kind of woman entirely, and she was a hero. It would be poetically just for her to replace Jackson and I love the thought of her soft and majestic face on money. Not to mention the satisfying contrast of her ferocious name.

Would Mankiller want to be on a banknote? She once said, “One of the things my parents taught me, and I'll always be grateful is a gift, is to not ever let anybody else define me.” She was a woman who stayed true to herself and her tribe — not given, it seems, to self-aggrandizement. But if her face appearing on American $20 bills sent the message that the voices and histories of her people — the people whose lives she worked so hard to improve — are increasingly in the public consciousness, then surely she would not complain. Lets only hope that that is indeed the case.

Images: Getty Images (1)