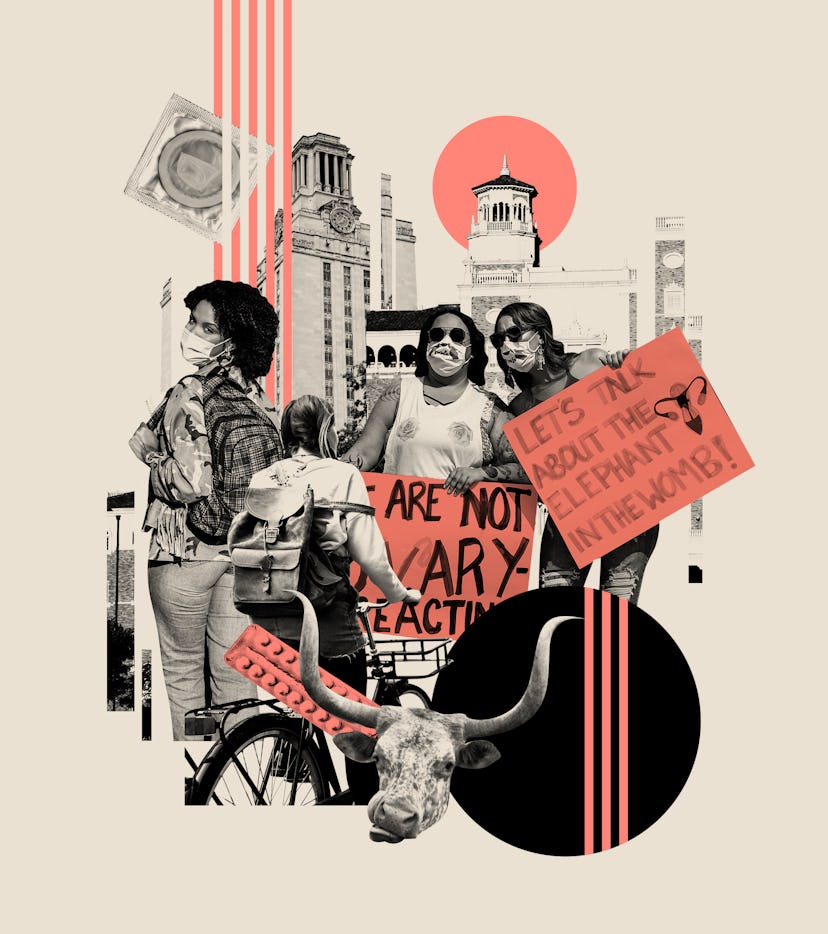

Reproductive Health

In Texas, The Return Of Whisper Networks

It’s “just terrifying,” says a sorority president of the new abortion law.

Carmen, a college student at Texas Tech University, was walking near her campus’ Student Union Building when she spotted a woman handing out gum in a space designated as a “free speech area.” Curious what the catch was, Carmen accepted the gum, which came with a modern, jewel-toned comic of two women talking. On the backside was a QR code linking to information about how to buy abortion pills on the down-low.

Carmen, 19, was in awe. This was Lubbock, Texas, a city that had just banned abortion and declared itself a so-called Sanctuary City for the Unborn. And it was days before the state would make abortions illegal after six weeks, which is before most people know they’re pregnant. “This isn’t the safest place to be doing something like this,” Carmen remembers thinking.

On Sept. 1., Texas’ new law took effect, outlawing abortions once a “fetal heartbeat” is detected, and turning citizens into bounty hunters who snitch on anyone who helps people get abortions after that timeframe. Their reward: potentially $10,000.

I've spent the past six weeks in Texas talking to students like Carmen, who asks that we omit her last name to protect her identity. It’s a self-selecting group of those willing to talk about abortions with a reporter. By and large, they are indignant: The new law is another thing they have to worry about, beyond combating rape culture, leading a sorority, or applying to grad school. Some say SB 8 makes it harder for them to control their futures, while others focus their frustration on the politics that turn them into “pawns.” While all the students I spoke with cite a dedication to birth control, most say they’d find a way to quietly flee the state if they needed an abortion.

Since accepting the gum, Carmen has become an ambassador for Plan C, an organization that shares information about how to buy pills online to discreetly end a pregnancy, which the FDA has approved up to the 10th week. She expects residents of Lubbock, where 62% of voters opted to ban all abortions there in May, will be “headhunting” for anyone wanting to end a pregnancy in their city, where 40,000 college students make up 15% of the population. She feels now is the time to be brave and is posting stickers with that QR code around town. (The Sanctuary City decision hasn’t been well tested in court.)

One of Carmen’s friends thought she was pregnant in the spring. “You think, ‘That’s never going to happen to them.’ But the reality is, it’s never going to happen to them until it does,” says Carmen, who was shaken by her friend’s experience. “To add more guilt to it, if [they] ask for help, [they’re] putting that [other] person in danger.”

In mid-September, she made an appointment to get a birth control implant in her arm in order to avoid the “user error” of missing birth control pills. Although her family is upper-middle class, she says she doesn’t have the money to leave the state if she got pregnant and probably wouldn’t tell her parents. She says she would probably buy medication online to have an abortion at home.

Nearly 400 miles southeast of Lubbock, Alyssa Le sits in her apartment in Austin, Texas. The 19-year-old, whose father is a gynecologist, operates Locket from her off-campus bedroom, in a home she shares with three roommates. Locket is a hotline for Texans to privately ask questions about birth control and how to legally access it without parental consent. Since Sept. 1, at least three clients have asked her about SB 8 or how to order abortion pills online. Alyssa answers questions about the law, but is afraid of getting sued if she provides information about medication abortions. So she holds back, and doesn't give any formal recommendations about ending a pregnancy.

She and her friends talk about their anxiety to not get pregnant and how they need to better track their menstrual cycles. Other students at the University of Texas at Austin sometimes carry signs protesting the new law, Le says, but she and her friends haven’t yet.

Mostly, she’s frustrated. The majority of Texas’ public schools teach “abstinence-only” sex education, and the state has one of the highest teen birth rates in the nation. A 2019 study found Texas teens were slightly less likely to have sex than other American teens, but those who did were more likely to forgo condoms or birth control. “The people who already have access to birth control will continue to be aware of safe-sex practices,” says Le, whose East Asian parents are both physicians. But she worries about the teens and young adults who are on their parents’ health insurance and afraid to broach the topic of birth control.

Le grew up middle class. If she needed an abortion, she says traveling to another state “might be a realistic option,” although she hasn’t talked to her parents about whether she’d have their financial support. Abortions in the first trimester typically cost $500 and up in Texas, and driving distance to the nearest clinic jumped from 17 miles to 247 miles for the average Texan after the law went into effect.

For now, she’s focused on ensuring people have reliable birth control so they never have that problem. “Sometimes people [would] say, ‘I’m not super sexually active,’ or, ‘it’s not a big deal right now,’” she says. “[But] the law puts this on the forefront of a lot of people’s minds. ... They’re slowly changing their priorit[ies] when it comes to birth control.”

“If you are assaulted and the pregnancy test comes back positive, no matter how pro-life you are, you’re going to consider your options, and you need to have those options available.”

A few hundred miles away, Laura* hops on a Zoom call from her apartment. She’s the president of a sorority at a major Texas university and says it’s “just terrifying [the legislature] even passed this.”

The 20-year-old uses an IUD for birth control and wants to go to medical school. She’s confident she won’t need an abortion but is nervous for her friends, some of whom don’t use birth control. They don’t talk about SB 8 as a sorority because her sisters have varying political and religious views and “don’t want to make others feel uncomfortable,” although some talk about it individually. She doesn’t know that any of her sorority sisters have had an abortion, although she knows one student from another who has. Some of her friends can probably pull together the money to travel out of state, she says, but not all can. “I don’t think it’s going to stop people from having sex with their boyfriend or husband, but it will make them constantly fearful,” she says. “I don’t know anyone who’s been in that position yet, but it definitely causes fear.”

Laura is an activist. In addition to her Greek life responsibilities, she’s also the chapter president for an organization promoting women’s social and economic opportunity, which includes access to reproductive health care. Opponents of SB 8 say it will primarily affect young and disabled people, and low-income women of color. What upsets Laura most about the law is that anybody can file a lawsuit to enforce it. “Someone who is the rapist can’t sue, but their family can sue, their frat brothers can sue. Not only are [rapists] not held accountable so often, but this is almost like rewarding them,” she says.

She could have found herself in that position her freshman year. She says said she was a victim of sexual assault on campus by another student but never filed charges or a complaint with the university. Two weeks later, her period was late. “I was getting worried, and I think it was late because I had a lot of PTSD and wasn’t eating,” Laura says. She took a pregnancy test. “Thank God it was negative, but it so easily could have been positive,” she says. “That was definitely one of the scariest moments of [my] life. If you are assaulted and the pregnancy test comes back positive, no matter how pro-life you are, you’re going to consider your options, and you need to have those options available.”

Paulina also requested we omit her name to protect her privacy. “I think everyone’s had a pregnancy scare before,” the 20-year-old says from her Washington, D.C. apartment, recalling conversations with friends. She left Texas in August, just before SB 8 went into effect, and will be away from the UT Dallas campus for a year. (She has an internship to work on geographic information system mapping and then plans to study abroad.) Over the summer, she saw how the law had created a “weird, really emotional and scary political conversation.” It’s reassuring to be away, she says now, but her friends on campus are scared, uneasy, and angry. She is due back on campus in fall 2022 for her senior year.

She’s on birth control pills, but if she got pregnant, getting an abortion “would absolutely be something I [would] consider when contemplating the rest of my life and my career,” Paulina says. Her biggest concern is making sure she can safely end a pregnancy without getting herself or others in legal trouble. She feels it’s ironic that the new law went into effect with the new school year, bringing with it a new sense of monthly anxiety.

“It’s not just exam weeks [now],” she says. “It’s, ‘Is my period going to come?’ week.”

*Name has been changed to protect the interviewee’s privacy.

If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, you can call the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit hotline.rainn.org.

This article was originally published on