Self

The Real Reason Gifted Kid Burnout TikToks Are Going Viral

“I can’t talk right now, I’m doing sad gifted kid burnout sh*t.”

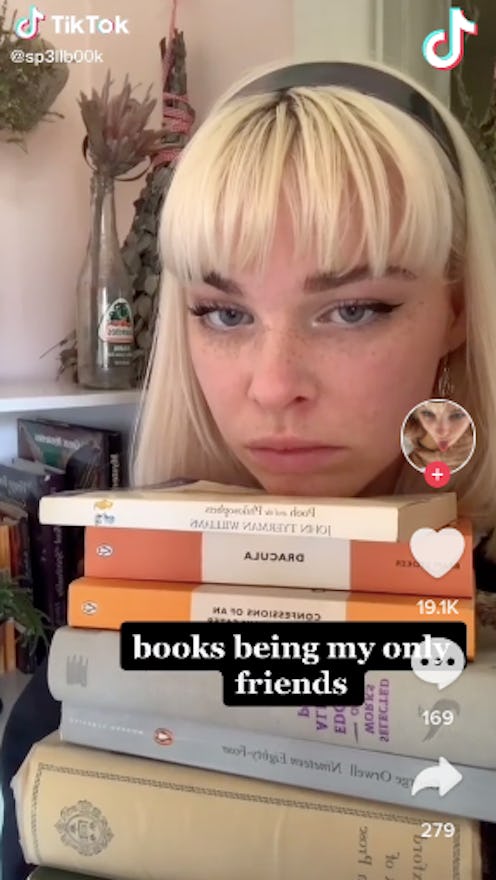

Sometimes a trend comes up on TikTok that can hit you right in the feels: a breakup lip sync, a particularly emotional sea shanty, maybe a really relevant audio about depression. But one theme that’s been going around centers on being labeled a “gifted kid” — or, more specifically, what happens when smart kids grow up. The idea of “gifted kid burnout” has been a meme for a while, and it’s found new life with TikTokers — the audio “can’t talk right now, doing sad gifted kid burnout sh*t” is everywhere right now. Experts tell Bustle it’s not just fun and games. People who excelled academically as kids, and got attention and rewards as a result, can face genuine challenges in adulthood.

One of the major difficulties facing former top-of-the-class kids, therapist Heidi McBain LMFT tells Bustle, is perfectionism. This might look like finding it hard to pick up new hobbies or skills if you’re not immediately good at them, or feeling sidelined at work if you’re not immediately promoted to CEO. “The perfectionism cycle can leave people feeling burnt out because it is never-ending,” McBain says. The more you try to be perfect, the more you’ll inevitably fall short. If you keep pushing, you’ll risk flaming out.

People who were told they were brilliant as a kid “may feel as if they have an obligation to perform at a particular level at all times,” counselor Lawrence Lovell, LMHC, tells Bustle. A study published in Journal For The Education For The Gifted in 2019 found that highly intelligent teens tend to be really perfectionist compared to their peers. If you feel that you’re only worthwhile if you get everything right, you’re more likely to be depressed or overworked as an adult. These heightened expectations, Lovell says, mean heightened stress — and, he adds, people who hold themselves to such high standards are also less likely to leave room for rest and recovery.

For people who base their self-worth purely on achievements, it can be hard to take rejection or failure, or to truly appreciate successes. “Life will never be perfect enough,” McBain says, which can make you less satisfied with life in general. The Terman study followed 1,528 high-IQ children from their childhood in 1921 for the next 80 years. An analysis of their lives published in Gifted Child Quarterly in 2020 found that those who were more aware of their “gifted” status when they were young were less likely to rate their life accomplishments positively as adults.

On the flip side, you may simply not want to do, well, anything. Another study in Gifted Child Quarterly in 2020 found that many talented kids don’t adjust well to college life, and start underperforming. Some take on too much, while others find the new challenges and learning situations difficult.

Some scientists think this shift comes down to how you view your own intelligence. The 2019 study in Journal For The Education of The Gifted also found that very smart teens tend to think that intelligence levels are fixed: that is, that they don’t change over time, and can’t be increased. Professor Carol Dweck has found that when kids are labeled as talented, they grow up seeing challenges as their enemy.

“Such children hold an implicit belief that intelligence is innate and fixed, making striving to learn seem far less important than being (or looking) smart,” she wrote in Scientific American in 2015. “This belief also makes them see challenges, mistakes and even the need to exert effort as threats to their ego rather than as opportunities to improve. And it causes them to lose confidence and motivation when the work is no longer easy for them.” Sound familiar?

If this feels relatable, McBain says, you might benefit from speaking to a therapist who understands the perfectionism cycle, and can help you stop looking at your life through the lens of your “lost potential.” Lovell suggests looking at the stories you tell yourself around work and performance. “Is the narrative positive or negative, helpful or harmful?” he says. Therapy, and the support of friends or professional mentors, can help you un-learn these narratives and adopt some healthier ones over time.

McBain also suggests focusing on what you enjoy and what brings meaning into your life. ‘Make time for daily self-care such as meditation, exercise, journaling, mindfulness, and so on.” Life isn’t about achieving gold stars in everything, even though it can take a long time to unlearn that.

Experts:

Heidi McBain LMFT

Lawrence Lovell LMHC

Studies cited:

Almukhambetova, A., & Hernández-Torrano, D. (2020). Gifted Students’ Adjustment and Underachievement in University: An Exploration From the Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Gifted Child Quarterly, 64(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986220905525

Frey, B. (2018). The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Vols. 1-4). Thousand Oaks,, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781506326139

Holahan, C. K. (2020). Achievement Across the Life Span: Perspectives From the Terman Study of the Gifted. Gifted Child Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016986220934401

Mofield, E., & Parker Peters, M. (2019). Understanding Underachievement: Mindset, Perfectionism, and Achievement Attitudes Among Gifted Students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42(2), 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353219836737

This article was originally published on