Eating Disorders

The Wild West Of Health Care

“Fingers crossed!” could be the official motto of the eating disorder clinical profession.

Content warning: This story discusses eating disorders and body image.

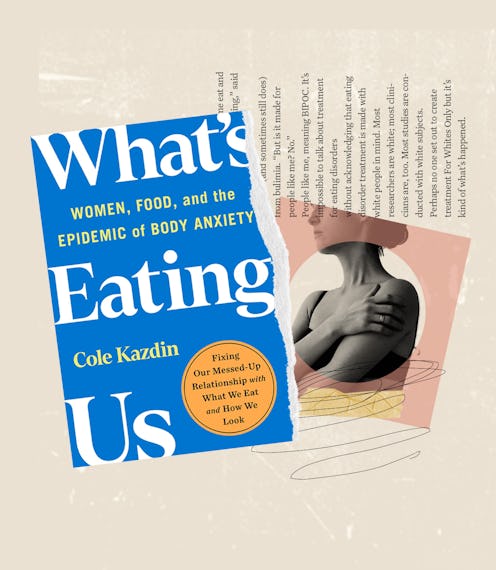

In 2008, when journalist Cole Kazdin sought treatment for bulimia, she had a few advantages on her side. She’s white (the majority of research around eating disorders has centered on white women). She could afford to seek professional help. And perhaps most interestingly, her father was the president of the American Psychological Association. Surely, if anyone were able to access high-quality care, it would’ve been her. And yet, her road toward becoming “recovered ish,” as she writes in her new book, took over a decade and was hardly straightforward. That experience led her to investigate the flawed systems — from the diet industry to the research community and beyond — that make it nearly impossible to heal (and stay healed) from eating disorders. The result is her new book, What’s Eating Us: Women, Food, and the Epidemic of Body Anxiety, out March 7.

Nearly 30 million Americans will have an eating disorder in their lifetime; it’s one of the most deadly mental illnesses, on par with the opioid crisis. “The relapse rate is anywhere from 40 to 70 percent to ‘who knows?’” Kazdin writes (citing a 2020 study published in Current Opinion in Psychiatry). It’s a serious epidemic, but it’s not often treated that way. As she illustrates, there’s a dearth of research on the subject, leaving the medical community with few guidelines.

If you break your leg, a doctor knows to put you in a cast and give you crutches. But if you have anorexia, bulimia, binge-eating disorder, or another form of disordered eating, the path forward is less clear. As Kazdin writes, “Recovery doesn’t just feel elusive; it is. According to the National Eating Disorder Association, ‘Eating disorder researchers have yet to develop a set of criteria to accurately define what factors are necessary’ to maintain recovery.”

What’s Eating Us? is a fascinating and frustrating read. It painfully highlights how difficult it can be to find adequate care, even though issues with food and body image serve as an ever-present backdrop to life for the vast majority of women. In this excerpt, Kazdin explores the obstacles facing those who attempt to seek treatment.

There are many, many treatments for eating disorders and only a few of them maybe kind of sort of work for some people, some of the time, best case scenario. “Fingers crossed!” could be the official motto of the eating disorder clinical profession. There’s a lot of great research and researchers out there. But eating disorders are less understood than many other mental illnesses. Which is not to say there can’t be positive results with particular therapies. There absolutely can be. But it takes an unruly amount of research to sort through the noise and learn what has the greatest chance for success. And once you do, you may not be able to find a qualified practitioner.

“There’s a lot of mediocre treatment for eating disorders,” said NEDA co-founder Ilene Fishman. Anyone can say they specialize in treating eating disorders. “Even people who have their certification about eating disorders specifically, even then, some of these people are newly out of school, they haven’t had clinical experience. It’s very hard to find.”

Back in 2008, when I sought care, treatment wasn’t regulated in any way and it still isn’t. There are a lot of therapies: CBT, and an updated version (that didn’t exist yet when I was in therapy) called CBT-E, E for enhanced. Dialectical behavioral therapy, which employs many aspects of CBT, while additionally teaching mindfulness and regulation of difficult or painful emotions. Family therapy, for children suffering from eating disorders and their families. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, focusing on sitting with unpleasant thoughts and emotions. Then there’s psychotherapy, where you talk to a therapist, equine therapy, where you talk to a horse, art therapy, dance therapy, and many, many others. CBT and DBT are considered “evidence-based” for treating adults with eating disorders, meaning there’s a solid backing of research behind them, and positive outcomes. FBT is the only evidence-based treatment for children and teens. Often, therapists combine modalities for a multidisciplinary approach, for example: DBT and art therapy. The very best ones kind of work. Hopefully. Fingers crossed.

It is very, very easy for a person with a life-threatening eating disorder to wind up at a treatment center with a fabulous reputation and end up painting watercolors. Cutting out paper dolls. Riding horses.

But hospitals and residential facilities employ all kinds of methods that have never been researched thoroughly with eating disorders. A lot of therapists are winging it. It is very, very easy for a person with a life-threatening eating disorder to wind up at a treatment center with a fabulous reputation and end up painting watercolors. Cutting out paper dolls. Riding horses. Which are all lovely and probably soothing activities, but may not make any positive impact on healing an eating disorder.

“It’s true,” said Walter Kaye, psychiatrist and founder of the treatment center at the University of California, San Diego. “There is no standard of care.” It’s depressing to hear it from him. Kaye is a leading researcher in the field and has worked for decades to improve this state of affairs. His UCSD facility is widely recognized as one of the best treatment and research centers in the country. “Many untested but superficially appealing treatments are marketed direct to consumer and direct to clinician. Outcome data are rarely published,” he co-wrote recently in the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

“Almost anyone can hang out a shingle,” said Cynthia Bulik, one of the world’s leading eating disorder researchers, and Principal Investigator of the global Eating Disorders Genetics Initiative funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. “Anybody can add eating disorders to their list of things that they treat and you have no idea how that person was trained, if they’ve been trained in evidence-based care, if they just checked that box saying yeah, I do that too, whatever. It’s horrible.” When I ask her views on equine therapy? “Don’t get me started,” she glared. “Really good when your bones are brittle to be bouncing around on a horse — just saying.”

And when treatment doesn’t work? “People are going to be chronically ill and they need to keep coming back for treatment, wow — it’s a good business model,” said Kaye. “You’re always going to have people who need treatment.” The more I learn about the for-profit eating disorder treatment landscape, the more it seems to have in common with the diet industry. Sell a product that doesn’t work, keep people coming back for more.

The absence of a true standard of care increases health costs for everyone—consumers, the health system, and insurers because patients have to keep returning to treatment over and over and over again.

That’s not to say things aren’t moving in a positive direction, albeit at a glacial pace. It actually used to be a lot worse.

“If you look at the big picture, things are getting better,” Kaye told me. “When I went into this field, nobody had any clues about anorexia. The treatments were kind of barbaric, they put people in a bed and a gown and you kept them there and wouldn’t let them get out unless they ate. There were all kinds of crazy ideas about cause and it’s really gotten better than that.” Since then, there have been significant improvements in understanding the illnesses and developing treatments. “It doesn’t happen in months or years,” he said. “It sometimes takes decades and unfortunately, that’s the pace of science.”

If there’s no standard of care for white girls, there’s even less of one for everyone else.

Deanna went into treatment for the first time almost 20 years ago, after her father, a cop, found fruit loops she’d thrown up floating in the toilet. She was 15, and entered a residential hospital where she stayed for three months.

“One of my counselors was like, ‘You’re going to die if you keep doing this,’ and I was like — Great!” she laughed. In the hospital, she roomed with another bulimic. Bathroom doors were kept locked, but Deanna and her roommate both managed to sneak in at various points to start throwing up again. “I was a rebel,” she said. “I was like, F*ck you, I’m going to do what I want. I think bulimia was a lot to do with rebellion because so many girls I met throughout this whole process were like, I’m going to do it my way. Very headstrong.”

It led her counselor to employ an unconventional therapy, holding her over the toilet, flushing it over and over, telling her each flush represented another year of her life gone if she continued her bulimia. “It was terrifying,” she shuddered in the retelling. “Was it the right thing to do? Probably not. But it did wake me up.” After that, she stopped throwing up. In the hospital, at least. She started again once she was home.

“It didn’t cure me,” she said of her time in the hospital. About a year or so after she was out, she was back in the same hospital. Since, she’s spent much of her adult life in and out of various therapies and support groups seeking any degree of peace and healing. “I had a hard time finding help,” she said. “The right help.” She’s still looking.

It’s relevant here to point out that Deanna is white and I am too. If there’s no standard of care for white girls, there’s even less of one for everyone else.

“I think treatment helped me eat and helped me stabilize my eating,” said Gloria, who’s suffered (and sometimes still does) from bulimia. “But is it made for people like me? No.” People like me, meaning BIPOC. It’s impossible to talk about treatment for eating disorders without acknowledging that eating disorder treatment is made with white people in mind. Most researchers are white; most clinicians are, too. Most studies are conducted with white subjects. Perhaps no one set out to create treatment For Whites Only but it’s kind of what’s happened. Gloria’s parents are Mexican, and she grew up all around Southern California. Around age 10 she started binge eating, which developed into bulimia in her late teens.

In her twenties, she went in and out of various programs that she often couldn’t fully commit to because of her work schedule. (“Who the f*ck can afford treatment?” she asks.) And even though she wanted help, the finite course of treatment only added more pressure. “There’s no room given for people who aren’t ready to give up their eating disorder,” she told me. “I want to be met where I’m at. It’s unfair to put this expectation on people, wanting them to seek recovery. You don’t know my life, you don’t know how my eating disorder has helped me survive till now. And now you’re telling me I have to stop?”

It led her to take a DIY approach, which isn’t uncommon considering the dearth of affordable, evidence-based treatment options. Even today, she scours academic journals to stay up on the latest research, educates herself as much as possible, and continues to dip in and out of her disorder as she needs it to cope with other stressors in her life.

“When I finally said, OK I’m ready, I want to recover, there was nobody waiting for me at the gates of eating disorder recovery, so I had to do it on my own.”

If you or someone you know has an eating disorder and needs help, call the National Eating Disorders Association helpline at 1-800-931-2237, text 741741, or chat online with a Helpline volunteer here.

This article was originally published on