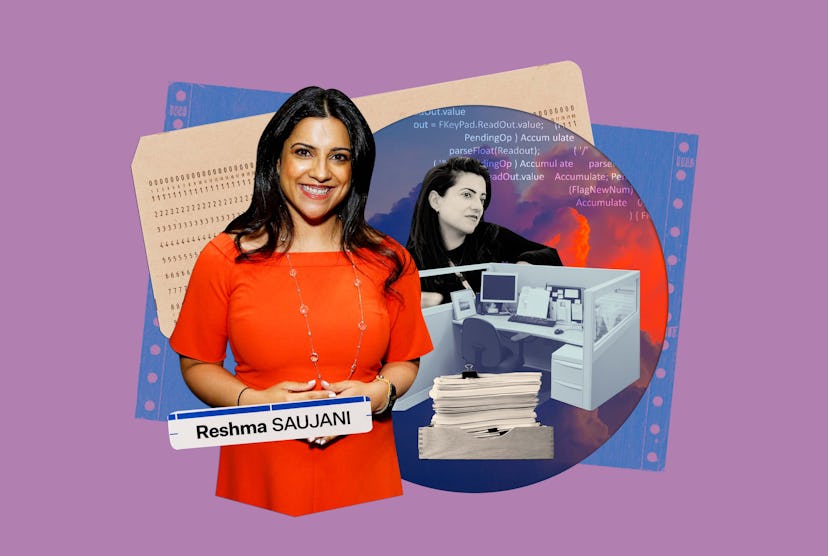

Burnout Confessionals

How The “Pressure To Be Perfect” Held Reshma Saujani Back

Before founding Girls Who Code, its founder hit rock bottom in an entirely different career.

In 2009, Reshma Saujani was a 33-year-old Wall Street lawyer with a dreamy salary, two Ivy League degrees, and a trendy East Village apartment. She was making more money than she’d ever imagined, in a role that was the culmination of over a decade of hard work. But the Illinois native was miserable. She was crying every day, sleeping too much, and drinking more than she wanted. “I felt like every night I was coming home and just falling asleep on the couch,” says Saujani, who’d been practicing law for seven years. “I had so much anxiety, I was burned out, and I was feeling it.”

Saujani wanted to quit but had shackled herself to $300,000 in student loans, courtesy of a master’s degree from Harvard University and a law degree from Yale. She’d hoped to work a couple years in the corporate world to pay off her loans — and her parents’ mortgage — before pivoting into public service, but she’d already worked herself to the bone. (Getting into Yale took three tries.)

“I found myself in that job I hated, in the life I didn’t want,” Saujani, who’s now 46, tells Bustle. She felt trapped. One day, her best friend called and said, “Just quit.” So she did.

Saujani is one of countless Americans who’ve gone deep into debt for their education and then taken a job they didn’t want for financial reasons. According to a 2020 report from the American Bar Association, more than half of law school grads have over $150,000 in debt at graduation, and over 40% of young lawyers in corporate jobs chose them simply because of the salary. Without the burden of her student loans, Saujani says she never would have entered the corporate world at all.

“We never actually build the muscle to figure out what we love.”

Like many parents, Saujani’s wanted the best for their daughter, which they conceptualized as a stable, high-paying job. They’d immigrated to the United States as Indian refugees fleeing Uganda in the ’70s, and were so proud of Saujani that they framed her first big paycheck in 2001. But knowing her parents’ journey made her decision more daunting, she says. “That pressure to be perfect, that pressure to be a good girl, was always with me.”

There’s no one way to quit a job, and Saujani didn’t have a strategy. She didn’t make a three-month plan or craft a detailed budget. Instead, she bore into the savings account she’d been building and bet on herself. When she told her parents she was quitting, her dad’s response was immediate: “Finally.”

A few months later, Saujani started a run for Congress, for a seat representing New York in the House of Representatives. “I got my ass handed to me. I got crushed,” says Saujani, who had no previous electoral experience. “But it was the best experience of my life.” She felt like she was doing what she was meant to be doing — engaging in public service and advocating for others.

Since then, she’s founded the education nonprofit Girls Who Code, run for office again, written four books, and started a movement for equality for working mothers. Saujani still hasn’t paid off her student loans, but she doesn’t regret the path she chose. “As women, we’ve been taught to do the things that we’re good at,” she says. “We never actually build the muscle to figure out what we love.”

While Saujani still experiences occasional burnout, she finds it less debilitating now. The mother of two might have trouble sleeping or get inexplicably emotional while watching a movie, but she’s not crying herself to sleep every night. She’s better at identifying when “I’m spent, I need to take a break,” she says. (It’s a feeling many working mothers are experiencing these days, she says, and the topic of her new book, Pay Up: The Future of Women and Work.)

Her advice to those considering a career switch? Figure out what you feel called to do. “So many of my career choices were based on what I thought I should do: another notch on my belt, another degree, another thing to make the Indian aunties proud of me,” Saujani says. “You have to ask yourself, Why do you see this as an investment in you?”

This article was originally published on