I Don’t Want To “Say” Anymore Names

We’ve gotten too good at memorializing victims of police violence.

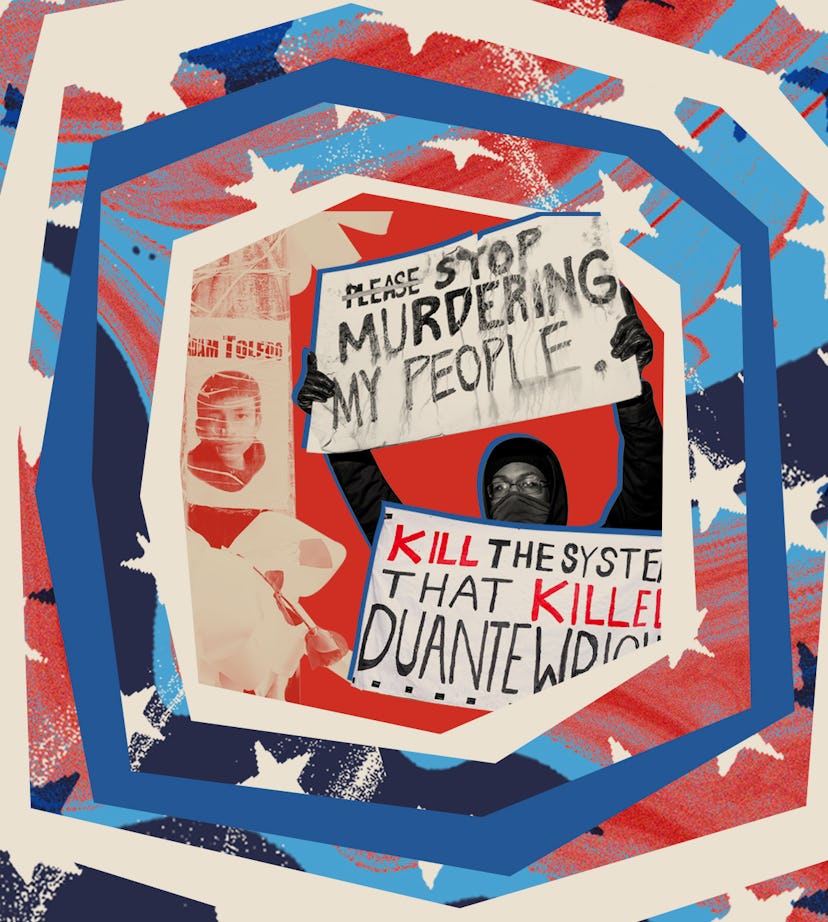

Adam Toledo. Iremamber Sykap. Daunte Wright. Anthony Thompson Jr. Ma’Khia Bryant. I don’t want to “say” any more names. I don’t want to commit to memory the death of one more child, father, mother, cousin, or sibling at the hand of United States law enforcement. And I don’t want to describe the names of those I can’t recall in the moment as “countless others.” At the core of me, I just can’t. And every approaching day is another in which I have to.

Spring rounded the corner, carrying with it the familiar scent of Black Summer. Black Summer is what I’ve come to call the collection of spring and summer murders which, last year, spurred international outcry: #blackouts, Black Lives Matter protests, “We here at [corporation]” statements of allyship, and anti-racism book lists. I expected the return of the sun to bring back these memories, but not the murders. I think back to the difficulty of this time last year — a time filled with fearfulness but also the possibility of hope, the chance that a global community speaking up and speaking out might alter the tide of systemic abuse against BIPOC people. I wasn’t naive. I didn’t expect the world to change overnight. But I did expect it to progress, incrementally, such that the spring of 2021 would not have already seen so many deaths at the hands of law enforcement — this time, mostly teenagers, including the youngest of those people, Adam, only 13.

Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Nina Pop, Tony McDade, Elijah McClain, George Floyd. It has been less than a year since I took to saying those names regularly and the return of summer also fills my nose with the scent of their blood. Black and dried. Evaporated into sidewalks and the distant sound of ambulances. Buried beneath the ground. Bleached clean in the sanitized memory of painted memorials — selfies and snapshots lifted from victims’ social media feeds and made iconic so that people can count them as part of a cause, instead of remembering that they lived.

This time around, the social media memorials trouble me more, because they arrive before I can even grasp the gravity of another lost life — often, before I have seen reports of the police killing in the news. I find an onslaught of Instagram illustrations of the latest victims before I know what they looked like as people. Living this way is unnatural and uncanny. The call for justice and remembrance both so persistent and so feeble. It tries to breathe life into a system of justice we cannot resuscitate.

All of us are feeling it. Murder fatigue. From people in Black, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous, and broader communities of color all the way down to the people who America’s history with BIPOC death was designed to protect. Everyone I’m close to is sick with it. And I am too.

It’s hard to describe, like being in two states of time at once. I’m still reverberating with the toll last summer took on my body — my protesting, my activism, and the emotional labor asked of me in the education of allies. That summer left me destroyed. I got so tired that, by August, I was contemplating making it my last one. I mention it here because I’m not the only Black person in my circles who has confessed the same sentiment to loved ones: What’s the point in doing this work if no one wants me to be here? And I mention it because I am lucky. I have great friends and a fantastic clinical psychologist who continue to support me in my healing. But I was diagnosed with a disease my friends in predominantly Black countries often refer to as “Post Traumatic Slave Disorder”: complex PTSD. “Complex” is fitting. Because it reminds me the best medicine for PTSD is to remove the stressor but, I live here, in this world, in this body, in this America. This is my home.

On the brink of another season of violence, our attempts to keep the fight alive through social media visibility risks turning the accumulation of our loss into an abstraction of our pain. The memorials are becoming rote. Images of our victims are lifted so quickly from their Facebook accounts and TikTok feeds, we barely have the time to process the specificity of the life lost. We argue in the comments over whether or not the death had some validity — because we are tired of believing that grieving is all we’ve got. And I get that. But it puts a distance between ourselves and these deaths that’s better suited for an anti-racism PowerPoint.

I don’t have complex PTSD because I recognize I could be the next victim on the news. I am here because I grew up one hour and one college basketball rivalry away from where Breonna Taylor was shot dead in her bed while she was sleeping. Because on April 20, the day George Floyd’s murderer was convicted, I am stopped cold in my tracks by a DM from a friend who tells me Ma’Khia Bryant, shot down by the police that day, was his best friend’s 16-year-old cousin.

Images of our victims are lifted so quickly from their Facebook accounts and TikTok feeds, we barely have the time to process the specificity of the life lost.

That afternoon, I Zoom with my writing partner Tracey Waples, a groundbreaking music executive that Method Man & Redman shoutout profusely during their 4/20 Verzuz. Tracey and I briefly celebrate the Chauvin conviction that her mother, who marched on Washington in the ‘60s, callsa win for civil rights. But we can’t help but talk about Daunte Wright, and how George Floyd’s girlfriend worked at his high school. She talks about the number of baby-faced boys she knew, growing up in New Jersey, gunned down 20 and 30 years ago, who will never see their day in court. And how often when white people see Black artists use historical references linking slave patrols to the United State police force, they think we are speaking in metaphor when we’re actually reporting the pervasiveness of America’s racial violence precisely and truthfully.

Four years ago, my sister was detained by the police in the same manner George Floyd was. Arms behind her back. Knee at her neck. I think about this every day. I think about this every time I sit down to write for this website, with the picture of my Black face — composed and poised — at the bottom of each article. I try to shake this off so I can write for you. I call my best girl, francine j. harris, who won a National Book Critics Circle Award last month for her third book.

She and I try to unwind over FaceTime but end up comparing notes from the trial now that it’s over — each of us holding our breath the entire time, irrespective of the outcome. What has become so terrifyingly clear to me now, I tell her, is that none of the actions of the police in these circumstances are illegal. They are, in fact, ordained by the government to use the same lethal force on us that bounty hunters and border patrollers used on Black people, Mexicans, and Native Americans to take these lands, inhabited by people of color, and turn them into a nation of all-white states. I can’t write. I go to bed early.

I text a buddy of mine early the next morning to see if I can go to his house and finally finish this article. His couch is soft, his company pleasant, and his brownstone block apartment gets that good coffee shop light. I tell him I’m writing about murder fatigue, and he pulls up on his phone an article on a friend of his who was also shot down by the police, days after the Chauvin trial. Three times, the news report says. Why don’t we know his name? I ask him. I scroll through the article; its last update says the young man is still in the ICU, in critical condition. Oh, I realize, it’s because he’s not dead.

This is an article of exasperation. Because that is all I have. And I think it’s important to say so, knowing how many BIPOC people with platforms right now are being demanded to continue to be vocal in the fight against racial violence, as if the fight itself is enough to ease our pain. I mention the credentials of my girlfriends to point out that this struggle doesn’t recognize any accolade or privilege. As gifted as I’ve been with a pen, I don’t know how to fit the word tired into my mouth in a way that you can hear it.

On the day this article is due, just as I think I’ve mustered up the energy to write a closing paragraph, I wake up to a group chat message from my pod buddies sharing the latest NBC News report about Isaiah Brown. The person I’m loving right now is lying next to me. We lay in bed reading and rereading the article: Brown, Virginian man shot by the same police officer who had just driven him home. That doesn’t make any sense, my person says. We can’t say anymore. I ask him if I can hold him, because it’s the closest thing I can do to hold all the people — those countless names — that I cannot.