Activism

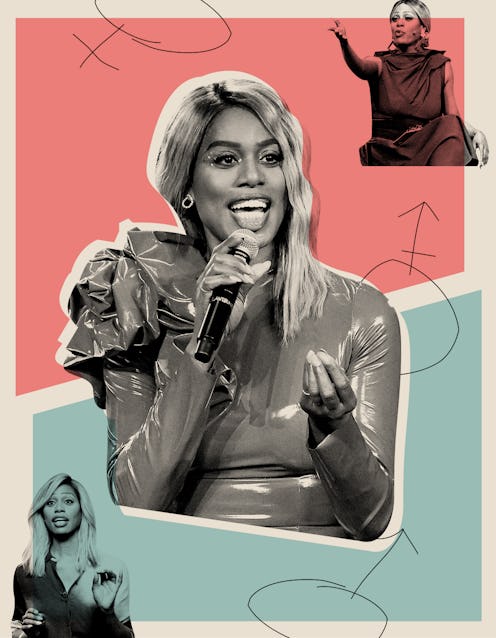

Laverne Cox On COVID-19 & The Lingering Trauma Of The AIDS Crisis

The Emmy winner joins a chorus of voices demanding diversity in medical research.

Growing up in Mobile, Alabama, Laverne Cox didn’t think there was a difference between boys and girls. “Well, if everyone's telling me I'm a boy, but I know I'm a girl, there must not be any difference,” the actor tells Bustle. Her third-grade teacher insisted she go to therapy, telling her mom she wasn’t acting the way someone assigned male at birth was “supposed to act.”

It was around 1980. The country was on the cusp of both a new decade and president. The newly elected Ronald Reagan was unprepared for the looming AIDS crisis about to rock the country. His press secretary, Larry Speakes, called AIDS “the gay plague.”

Having come of age during the AIDS crisis, Cox, now 48, is still working to unlearn things she was taught about gender and sexuality in elementary school. In the ’80s and ’90s, she says, resources for the trans and nonbinary communities weren’t easy to come by. Even now, when several organizations such as the Trans Youth Equality Foundation and the Trevor Project offer resources, trans people still face elevated risks of depression, anxiety, and HIV. They also face high levels of discrimination and stigma in the medical world, which can make getting care more difficult than for their cisgender counterparts.

The COVID-19 pandemic has renewed calls for inclusivity in medical research, given how the virus has disproportionately hit Black and Latino communities. Cox is currently working with Johnson & Johnson as the first spokesperson for the company’s (BAND-AID®)RED campaign, which aims to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS and the need for medical inclusivity.

Medical research often excludes trans or gender nonconforming people altogether, Cox says, and doesn't prioritize communities of color. She talks to Bustle about how growing up in the ’80s inevitably affected her understanding of identity, and how society can move forward.

You've talked publicly about growing up and trying to distinguish gender from sexuality. Do you remember the first time you questioned traditional gender roles?

I think it was in third grade. My third-grade teacher called my mother on the phone and said, “Your son is going to end up in New Orleans wearing a dress if we don’t get him into therapy right away.” So I was taken to a therapist, basically to fix that I was very feminine. I did not act the way someone assigned male at birth was supposed to act, according to my teacher, to my mother, to all the others. When I was in the therapist's office, that was the first time I remember questioning gender expectations. I was just myself up until then. Everyone was telling me I was wrong, and I shouldn't hold my hand this way, or I shouldn't walk this way or talk this way. But when the therapist asked me if I knew the difference between a boy and a girl, I said, “There is no difference.” Everyone was telling me I was a boy, but I knew in my heart, soul, and spirit that I was a girl. I knew I was a girl. So I assumed that there must not be any difference between boys and girls.

Did you have any resources to help you parse out gender for yourself?

I was, like, 10 years old in 1982, at the very beginning of the HIV/AIDS crisis. In terms of gender, there were no resources for me in the ’80s. All [I had] was television. I knew about trans people on television, but it wasn't something I identified with. The closest [person] that I identified with on television was Boy George, who was called gay, but he identified as bisexual at the time. There was nothing else. I was called gay because I was a very feminine kid. When I would go to the library, I wouldn't research gender; I would research sexuality. [Researching gender] just didn't occur to me, because of the way in which gendered behavior was conflated with sexual orientation.

What can parents do to help their children discover gender in a more inclusive and positive way?

When I look back on my childhood, the biggest thing would have been if my mother had said, “The way you walk is beautiful, the way you talk is beautiful, the way you hold your hands is amazing. Don't change anything about that.” I got into this [head]space where everything needed to be monitored, all of my gender expression. I had to monitor it so I wouldn't draw attention to myself. That was really hard for me. I think if I had someone had said, “The way you are is beautiful,” it would have changed everything for me.

You’re doing a lot of work to shed light on discrimination in medical studies. What are some real-world effects of non-inclusive studies?

Trans folks are almost always left out of research. We don't know exactly how many trans people exist in the United States. Everything we know is a guesstimation. So it’s major that trans folks are included in [HIV/AIDS] trials, because we are unfortunately still at a really high risk of transmitting HIV/AIDS. A lot of my work is about trying to lift stigma and draw attention to inclusivity around studies and data collection.

How do you envision a world where we can step forward from those errors, and heal from them?

There are so many things we have to unlearn. All those stigmas and misconceptions really just [stem from] miseducation. The re-education process is something we all have to be engaged with — as individuals, in government, and in our corporations. Every aspect of society has to be on board.

We’re in a moment of a global pandemic, right? There’s so much uncertainty, there's so much fear, and there's so much trauma. There are lessons we can learn from the beginning of the HIV/AIDS crisis [in] the early ’80s. The trauma piece cannot be underestimated. We are collectively traumatized around this COVID situation. There's PTSD around that. I know for me — coming of age in the ’80s, going through puberty and realizing my attraction to boys during the middle of an AIDS crisis, when people were dying in my community — there was so much trauma around sex and sexuality. That hasn’t gone away. It just hasn’t. So I think we have to be willing to have conversations [about trauma], and we have to be willing to engage everyone.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.