Rule Breakers

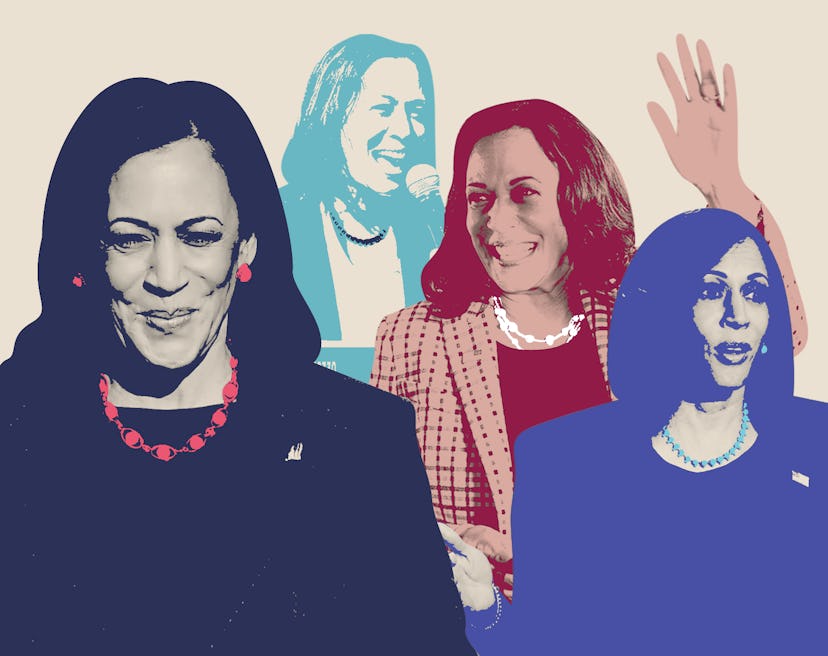

The Special Connection Between Kamala Harris’ Pearls & Her Indian Ethnicity

Why is her South Asian identity always mentioned as an afterthought?

Nearly all Hindu deities are adorned with pearls. Gleaming white or dark, like those Vice President Kamala Harris wore to kick off her presidential campaign in 2019. Hindu legend credits the pearl to the god Krishna, who conjured them from the ocean. Another tells of him growing multicolored, fragrant pearls to flirt with women cow-herders. Seeing the pearls around Harris’ neck during her inauguration as “the first African American and first Asian American” to hold the office, I felt a mixture of pride and sadness.

Sadness that “Asian American” seems to always come second in phrasing. Sadness at the continued invisibility of Asian American as a political category, a voting bloc with rights and demands, a group with deep history in this country, as far back as the 17th century, when South Asians were first brought as indentured servants and slaves to the United States.

But pride that Harris had a progressive enough mother, Tamil American Shyamala Harris, née Gopalan. She nurtured her daughters as both brown and Black women. Kamala, she named her eldest, a Sanskritic and Tamil word for “born of a lotus,” a name of the Hindu goddess Lakshmi. Devi, her daughter's middle name, for “goddess.”

Against my pride and sadness, a shame also persists. A spate of recent anti-Black violence in India, along with India’s racist history, prevents me from shouting about how we should claim Harris louder, should make her Indian-ness equal to her Blackness — even though her vice presidency marks a watershed moment for Asian Americans.

After Harris’ vice presidential debate last October, her maternal uncle, Balachandran Gopalan, congratulated her via video. Listening to his amused, loving comments about his niece, it became abundantly clear how different the Gopalans are from some Iyer (Tamil Hindu Brahmin) families also living in Chennai, a southeastern Indian city. My extended family is from Chennai. I marvel at how different her family’s beliefs are from the narrow, provincial, outright racist and casteist perspectives of some members of my extended family.

When my brother and I were in elementary school, we would spend summers “back” in India. It was the ’80s and early ’90s. I would get asked by my father’s relatives, in cautious, horrified voices, if Black Americans swam in the same pool as us at the YMCA in Queens, New York. Vicious comments came from older, male relatives, who perpetuated the racist stereotype of the "welfare queen."

My paternal relatives talked of violence against Indian immigrants by Black Americans, as if negatively portraying other people of color would win them acceptance from whites, as if it might make the actual violence enacted upon us, mainly by our white neighbors, more bearable. As children in Flushing, Queens, white neighbors threw bricks at us while we walked home from school, vandalized our driveway and mailbox, called out slurs, ordered my Korean American friend and me to take off our pants, and then pursued us when we ran away. One time a gang of white children tried to beat up my brother when he was in grade school. An Indian neighbor intervened.

My father’s side of the family was more overtly religious than my mother’s and thus less inclined to question the unjust social order created by caste. There was constant, resentful muttering about shudras, the Sanskritic and derogatory Tamil term for Dalits, which is outlined in the manava dharma shastra (The Laws of Manu) as the lowest caste. For some members of my paternal family, shudra was also their conceptual understanding of Black, of any member of the African diaspora, and of India’s ancient Dravidian peoples.

"Kamala, she named her eldest, a Sanskritic and Tamil word for 'born of a lotus,' a name of the Hindu goddess Lakshmi. Devi, her daughter's middle name, for 'goddess.'"

Vice President Harris visited India in the 1970s, based on photos of her trips to Chennai. As a biracial little Black girl with American-accented English, limited Tamil, and nice clothes, Harris’ hair and features would have been immediately perceived as “different” while walking on the roads of South India, and therefore a threat to the pukka — the “pure,” as defined by the Hindutva regime. A Black woman in India, of any age, risked being denigrated, stalked, or even attacked in choosing to wander alone.

In Sanskrit literature, “the pure” can also be translated to mukta, a word for pearls.

For Harris, her maternal family’s socioeconomic status likely protected her from danger, her grandfather a well-respected government employee. Her family home in Chennai likely would’ve had watchful servants, who would have guarded the little Harris girls on their visits, as would the chitthis Harris referred to in her acceptance speech.

But just because she and her sister were protected doesn’t mean other Black people were treated fairly. In India, Black residents have repeatedly faced mob violence, sexual harassment, and discrimination in public spaces, like the 2010 beheading of a Tanzanian national, the 2017 beating of a Kenyan woman who was pulled from a taxi, or the 2019 mob attack of a Nigerian national in New Delhi after an alleged scuffle with traffic police.

In 2019, Dr. Isa Danjuma, a Nigerian scholar who’d just completed a Ph.D. in New Delhi, spoke to Indian officials about the country’s new “Study in India” initiative. “India is a racist country,” he said. “Indians are not ready to accept foreigners, especially those from Africa.”

Does the virulent anti-Blackness expressed by Indian and Indian diaspora communities mean that we will never have the right to claim the vice president the way that Black communities can and should?

In the past few months alone, white and Black Americans have enacted brutal violence against Asian Americans, which, tragically, has longstanding historical precedent. I hope Harris' election prompts us to ask ourselves and each other questions about solidarity, so that her strand of pearls can be recognized as a signifier of both her Black sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, and her South Asian heritage, a heritage defined not just in terms of its images or jewels, but as a commitment to the struggle against casteism, racism, and inequality.

This article was originally published on