Rule Breakers

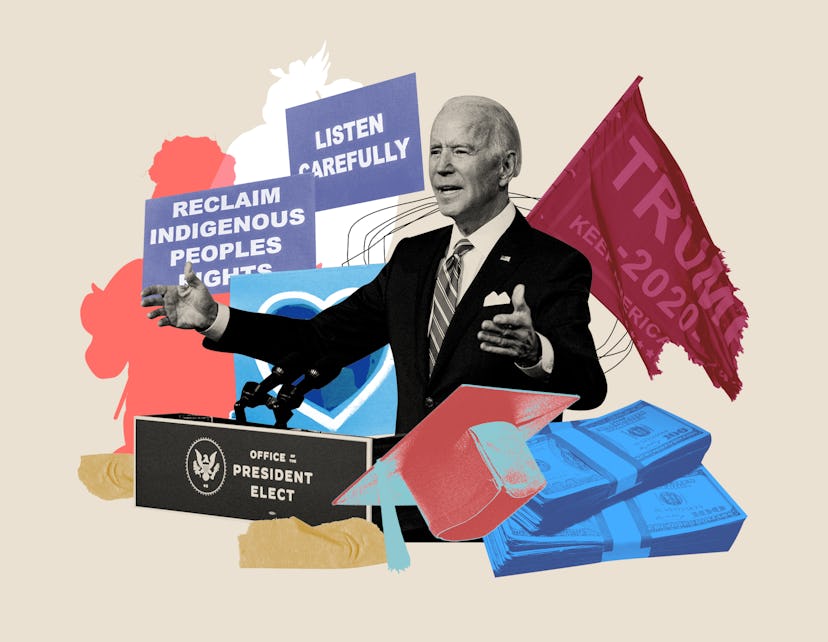

The Election Is Over. Now What?

Two veteran activists, Brittany Packnett Cunningham and Jenna Arnold, on building a better America.

Last month on Undistracted, the new half-hour podcast from Brittany Packnett Cunningham, the activist interviewed poet Nikki Giovanni for a Thanksgiving Day episode. They talked of racial justice and contemporary Judas figures, before Packnett Cunningham, a former third-grade teacher, asked Giovanni what she’d tell young children today. The poet's answer: “Your responsibility is to your dreams. It’s not to these people who are trying to hurt you. It’s to the future, and you have to keep your eyes on the prize.”

On the weekly podcast, Packnett Cunningham — a Ferguson Uprising activist, cable-news contributor, and former member of President Barack Obama’s policing task force — hosts a “who’s who” of intersectional feminist thought leaders, with guests ranging from activist LaTosha Brown to journalist Rebecca Traister. To celebrate the show’s launch, she spoke with Jenna Arnold, a national organizer of the 2017 Women’s March and former elementary-school teacher herself, whose new book, Raising Our Hands, invites white folks into anti-racist work. Over two conversations last month, they reflected on the 2020 election and a future for America.

Jenna Arnold: How are you? How’s your heart doing?

Brittany Packnett Cunningham: I appreciate that question. You know, it's honestly well. I just had a birthday, so I've been taking stock of things and feeling gratitude for my loved ones, and for breathing, quite frankly.

Happy birthday! How old are you?

I just turned 36.

I had my first kid at 36.

Well, there you go. It’s a good age.

Are you having babies?

We're talking about it. Prayerfully, we will get there soon. How are you doing?

I'm taking stock too. The dust hasn't settled yet for me. I’ve found language to be so painfully futile these days.

I definitely hear that.

In your podcast last month, you asked Nikki Giovanni about whether she's hopeful, and I'd like to direct that back to you. Are you hopeful?

I'm a real evangelist for what I call “disciplined hope,” hope that is informed by reality, and clear-eyed on how much we've accomplished in the past. We are certainly in perilous times. To deny that is to lie. But we've been in perilous times before, and we've abolished slavery. We passed the 19th Amendment. In moments when I'm feeling frustrated, I look to those folks who did it before to remind me that we can do it again.

Speaking of looking to the past, I’m increasingly hopeful by how many people are taking a fresh look at how and why the country operates the way it does. For example, the Constitution actually gives us tremendous flexibility to make structural changes.

I think often of that line in the Declaration of Independence, which is actually emblazoned on the wall at the National Museum of African American History and Culture — what we affectionately refer to as the "Blacksonian" — a line that says, “All men are created equal ... With certain unalienable Rights ... Whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it." If the institutions don't work for us, then we replace them. If the government doesn't work for us, then we change it. If the politicians don't work for us, we fire them and hire new ones.

Yes, and we have the architecture to make those changes quickly.

And I will say that, to this question of hope, a lot of my perspective has to do with the fact that I'm Black. I think Black people know America better than she knows herself. I think Black people certainly know America better than most white people do.

When I was doing research for my book, I talked with plenty of white women who prioritized comfort over justice. They would avert their eyes from brutality, so I'm not surprised by how many voted for President Trump.

I don't think any of us were actually surprised by the more than 74 million [people who voted for him]. Was it painful? Sure. Even the “water is wet” studies are still hard to read. You've now got four years of bigoted, xenophobic, racist, misogynistic, hateful, spiteful, egotistical, narcissistic evidence. And 74 million people said, "I want that."

One of the things I’ve found surprising in my research on American identity is how self-worth, or the lack of it, prevents people from being civically engaged. I crisscrossed the country, having closed-door conversations, and there was this idea of only being handed hope, versus finding it internally. I would argue that most of white America doesn't have a demographic watering hole where they can find hope.

And there are reasons for that. If your family immigrated from Ireland, France, Poland, or Germany, your ethnic community [was the group] that gave you housing, shelter, employment, and fed your children. Well, when European immigrants adopted whiteness as their protective shield, they essentially let go of all that. So we [Black Americans] have community because we're forced to because it is still our survival mechanism. That is why the Black church is an institution unto itself. We created that out of necessity. Yes, out of beauty, out of creativity, out of love, out of joy, out of laughter, out of family, but also out of necessity.

Most European immigrants assimilated into that white space in order to find not only strength in numbers, but in order to put themselves in the caste that was clearly receiving the most benefits. And if you have derived your self-worth from that over generations, then it is very difficult to let go of that thing. If you actually understand history, like I know you do, Jenna, all of it makes sense. We keep wringing our hands saying, “How can this be?” The trouble is we don't know our history, which is why we keep repeating it.

And if we can't agree on a common history, then it's impossible to co-create a future together. Recently I've heard Biden and Harris talk about "moral mandates" they received from winning the popular vote. What does that mean to you?

The moral mandate has to be progress, right? This is part of the reason why narratives matter so much, especially directly following an election, because whoever gets the credit [for a candidate's win] is who [often] receives the change.

Absolutely.

Part of the reason why [it's crucial to] make sure that story is clear — that Black and Indigenous communities were linchpin voters in this election — is because those also happen to be groups that need the most to change materially between the Trump administration and the Biden-Harris administration. And that's only going to happen if politicians understand who put them in office, right? It was people who not only showed up, but showed up in numbers that overwhelmed a system that was rigged against them because of voter suppression and digital disinformation. The impossibility of that outcome has to be shouted from the rooftops.

Right.

Our communities need audacious policy. We need student loan debt cancellation, which is a racial justice issue in as much as it is an economic justice issue. The climate crisis is a racial justice issue. There are some very clear and decisive actions that this White House needs to take. For me, the moral [mandate] is like, “White women, y'all need to go deal with each other. That is a long-term set of work that you have to do.”

And instantly. So many American white women avoid political discourse with those closest to them because it leads to conflict. We do this to "keep the peace,” to protect the performance that everything is fine. We opt-in to ignorance because it's easier than holding an entire system, or heaven forbid, ourselves, to account. But if people are afraid to be authentically themselves, they're unable to hold themselves to account.

It makes sense, but I don’t know if I can believe it.

No pardons should be granted.

Of course. So if we're not asking for a pardon, then that means we have to hold them accountable. Those are the two choices.

Yes. We have to hold white women accountable, while also holding the systems accountable that handed us the Kool-Aid to drink, the “drink” being this great American myth about a white picket fence, cute-enough kids, and a beautifully manicured lawn.

According to your theory, the conversation has to be "how are you actually stepping into what is truly authentic to you?" Because let's be very clear: There is an entire multi-billion dollar industry committed to helping white women step into their authenticity. There are wellness campaigns and yoga pants and brunches and podcasts. Why is that an investment being made? And do not hear me as saying that I don't believe all women should be able to step into their full power. I deeply believe that, and I'm invested in that in my own work, but only inasmuch as that stepping into our own power empowers all of us.

If me stepping into my own power as a cisgender woman disempowers trans women or gender nonconforming folks, then I've not stepped into the right thing. I need to step back, reassess, and step into something else. So clearly, something has gone horribly wrong.

It's easier for white women to be in allegiance with the patriarchy and white supremacy. Challenging the status quo means questioning the illusion of a merit-based society.

I talked to Rebecca Traister on Undistracted, [and] she was saying that to believe that white women were going to vote en masse for Hillary Clinton in 2016 was to ignore the history of how white women had been voting over many election cycles. Like we said at the beginning, there is work for white women to be doing with one another.

That reckoning has, horrifically, just begun. In the election, white women in swing districts and swing states shifted Democratic, particularly college graduates. We are starting to question the idea of America's "morality."

America as a moral project is complicated because if you ask the so-called founding fathers, their moral project was supposed to be freedom from tyranny, while they enslaved and colonized other people. So there's no reckoning with an American moral project without reckoning with American immorality at the root. It’s why The 1619 Project scares people who want to presume that America is a flawed but morally sound experiment, instead of realizing that the hypocrisy exists at the root.

We have to go get our history so we can go get ourselves.

It’s a project that marginalized people have always been committed to, because without it, it’s impossible to fully define our existence. I saw an early screening of the film Sylvie's Love. It’s a beautiful ’50s and ’60s classic love story, and it’s not about a Black person dying in the street or a cross burning in somebody’s lawn. It’s about love because people forget that in all of the marginalization and oppression, we have lived and loved, and raised children and cooked casserole and had torrid love affairs. Those stories never get told because we're still fighting to have the truth be told.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the year of the Women's March. It has been updated.

This article was originally published on