28

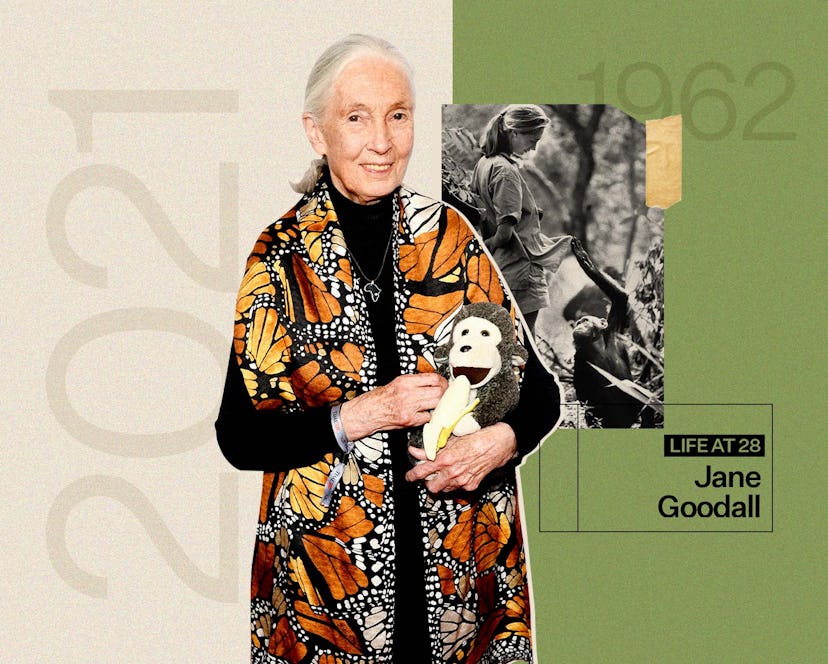

At 28, Jane Goodall Was Living In The Forest Doing Research

“Chimps don’t have weekends, so I didn’t either,” she says of her schedule in Tanzania.

In Bustle’s Q&A series 28, successful women describe exactly what their lives looked like when they were 28 — what they wore, where they worked, what stressed them out, and what, if anything, they would do differently. This week, primatologist Jane Goodall reflects on her third year of chimpanzee research in the Tanzania forests.

Five years before turning 28, Jane Goodall had traveled to Kenya to visit a school friend, whose family lived on a farm outside Nairobi. There, she’d met the renowned anthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey — a fortuitous meeting, as they’d hire the British 20-something to be their assistant. By 28, she was working in the forests in Tanzania’s Gombe Stream chimpanzee reserve, studying chimpanzees in their natural habitats. She’d already met David Greybeard, a chimp who used twigs to extract termites from their mound, which proved humans weren’t the only species to make and use tools. And as she neared age 30, Goodall started work on a Ph.D. in ethology at Cambridge University.

“Thanks to David Greybeard showing me the tool he was using, the [National] Geographic Society agreed to fund my research,” Goodall tells Bustle on a video call. “They funded a filmmaker, Hugo van Lawick, who came to document what I was learning, and eventually I married him. So it was his film, along with my detailed notes, that finally persuaded the scientific community that humans were not the only beings on the planet with personalities, with minds capable of solving problems, and above all, with emotions.”

Today, nearly 60 years later, Goodall lives in Bournemouth, England, in the attic of her late grandmother’s home. She’s spent the past year here with her sister, niece, and grand-nephews. She sits in the same garden she loved as a child, under the same tree she used to climb. “I called him Beech, and spent hours up there doing my homework, reading books, being up near the birds,” says Goodall, who’s now 87. “I have half an hour in the middle of the day to sit under Beech, having my sandwich, accompanied by a robin and a blackbird.”

Given her affection for nature, it’s no wonder she’s teamed up with the United Nations Environment Programme for a new initiative called Trees for Jane, which directly supports “Indigenous and on-the-front-line guardians of the forests,” and encourages everyone to plant your own trees if you can.

Below, Goodall reflects on her life at age 28, living through World War II, and dating advice.

At 28, you were two years into research in Gombe and had made some of the most important discoveries of your career. What were you interested in doing next? Did you have a plan?

No, my plan was to carry on because there was so much left to learn. There was no way I wanted to stop. I had just brushed the edge. Chimpanzees can live 60 years, and each one is an individual. To really get a grip on their behavior, it takes years and years. We’re actually now in our 61st year of studying the same chimps at Gombe. We’re about to start the fifth generation.

Living at a field site in the forest seems like an interesting set up. What was a typical day like for you? Did you have any free time on the weekends?

Every day, I set the alarm. I got up when it was still dark. I had a cup of something from the thermos, a piece of bread, and then I set off up into the mountains. Sometimes I put some peanuts into my pocket, sometimes I brought nothing. And I came down from the mountains just about as it was getting dark. Then I had some supper, cooked by the cook. Simple, very simple, [we had] very little money back then. And afterward, I wrote up my notes [of] everything I’d seen in the day, initially by hand because we couldn’t afford a computer. Chimps don’t have weekends, so I didn’t either. So that was my day, dawn to dusk.

When you and Hugo started dating, you were at a field site. It wasn’t a typical start to a relationship. Was there anything young people today could learn from your relationship?

Well, we were thrown together. We were out there, both loving animals, both loving being in nature. So it was pretty inevitable that we should decide, well, let’s do it together. And for a long time, it worked really well. We were a good team, with me doing the observation, Hugo recording it. Hugo editing the films. Hugo taking stills. Hugo satisfying [National] Geographic with his pictorial record and me satisfying them with writing.

I don’t think I have advice for young people. I was going to say you should share interests. We shared interests up to a certain point. And then things went wrong because we didn’t share everything. But there are some really successful marriages where the husband and wife have very different career interests. So I don’t think it’s set for all. It just depends on their personalities.

You’ve become a global icon in the conservation world. Was there a moment when you realized you’d become a type of celebrity? How did your life change?

It started when I helped to organize a conference to bring together people studying chimps in different parts of Africa. When I began, it was just me. By 1986, there were six other field sites. That’s when I realized how fast chimpanzee numbers were dropping. Forests were disappearing. So I went to that conference as a scientist — I had my Ph.D. by then — and I left as an activist. That’s when I began traveling around the world, I suppose, in 1987, because I had to find money to do it.

And about being an icon, more and more people gradually recognized me because of [National] Geographic, because I was their cover girl. People would come up and say, “Oh, you’re Jane Goodall. Can I have a signature?” I was horrified. I wanted to hide away. I hated it. I was very shy. And I used to go through airports with my hair loose [to hide my face]. I just didn’t like it at all.

But then there came a point when I realized, well, I want to save chimps and forests, so let me make use of this. I took to carrying little brochures around and started the Jane Goodall Institute. I’ve had to come to terms with it. It’s like there are two Janes. There’s this one talking to you in the house where I grew up, and then there’s the icon. They’re separate and yet, they’re the same.

Tell me about the house you’re in now.

It was my grandmother’s, and me, my sister, and mum came here when [World War II] broke out. [My uncle] came every other weekend from being a surgeon in London. During the war, we had to offer rooms in the house to anybody needing a home. If you had a spare room, that’s what you were required to do for the war effort. So they gave us two women. We didn’t like either of them very much, but there they were in the house. And that’s how I was throughout the war from age 5 to 10. And now, my sister lives here with her family: her daughter and her two grown grandsons. So we’ve been together during the pandemic.

Is there anything you’d tell your 28-year-old self to do differently?

I would offer my 28-year-old self to do just what she did. So she made some mistakes, but she learned from them. Nobody else was studying chimps at that time. It was uncharted. And looking back on it, I think that I made the right decisions.

What do you think your 28-year-old self would think of Jane today?

She’d just think, “Oh, that can never be,” and shrug her shoulders and carry on with what she was doing.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.