Rule Breakers

“Pretty” Won’t Protect You

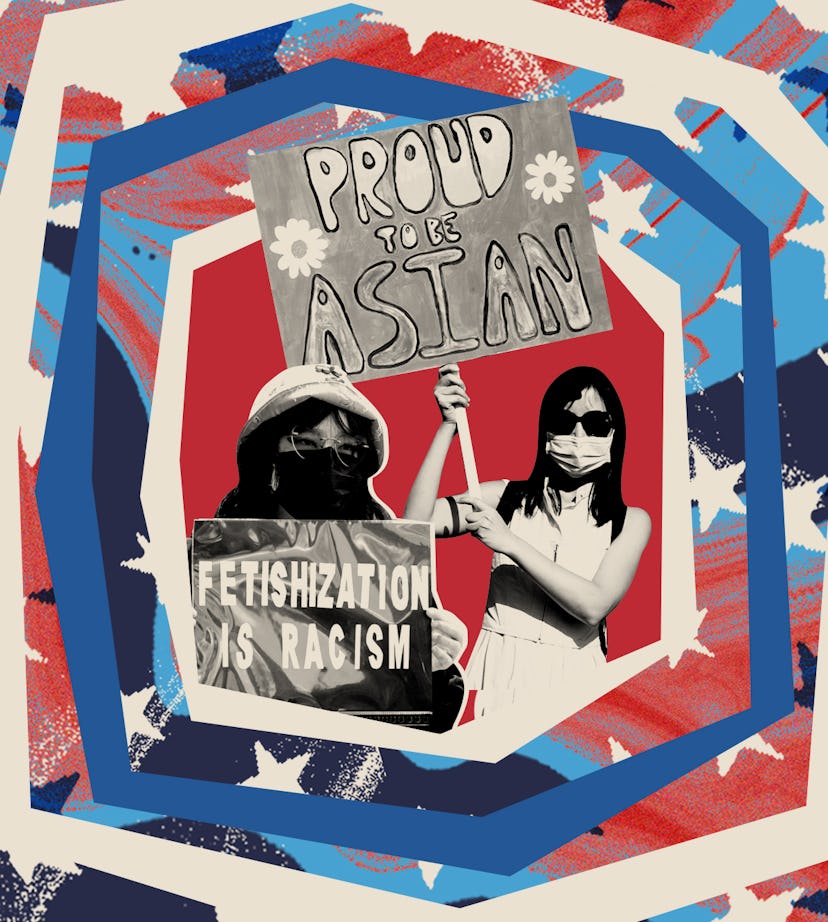

What Asian-American activists taught me about violence and desire.

“From a balcony, a man yells at me: ‘You need some white dick,’ and I turn into a boar.” Poet and activist Jane Wong read the line from her poem, “Everything,” clear and unbothered in a crowd full of West Coast whites. Its honesty was so loud, I clutched my chest like a strand of pearls. It was October 2019, back during a time when touch still felt possible, and the two of us were headlining a literary performance at a Seattle record store.

Parked in a nearby neighborhood after the reading, Jane and I talked about two things: balling our hands into fists when we fall asleep and being pretty. In the car late at night — locked doors, soft music, and a little A/C blowing — is my favorite place to hold court with my close friends, my favorite place for sistering. It’s there that I’ve gotten my best education on the lives of the people I hold most dear. That night, Jane and I talked for a long time about surviving “pretty” as an Asian stereotype of false privilege.

“Pretty” is a word we do not have enough conversations about. Prettiness isn’t the same as beauty, which can be internal and external, and which so many of us wonderful humans possess in abundance. Pretty is a measure of how well we fit into conventional expectations. Pretty is “good-looking,” “nice-looking,” or “passable.” Although we’re quick to talk about the ways we don’t measure up to pretty, we are often quiet about the ways that we do. In cultures where people of color are marginalized, “pretty” is a word that is synonymous with the white gaze — a measure of whether our attractiveness holds up to Western tastes. And, for a long time, Western culture has held Asian women up as pretty’s gold-standard fetish.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about that conversation in the weeks since a white man shot and killed eight people — including six Asian women — in Atlanta, Georgia. About the violence we overlook in fetishism, and about how the hypersexualization of Asian women — as feminine, submissive, and exotic — is so deeply ingrained in American culture that it’s often mistaken for something positive, or innocuous, instead of the racial bigotry that it is.

The problem is so pervasive it took me a long time to recognize it, despite being a woman of color. As a woman, I’ve been indoctrinated in the belief that pretty serves as a protection from violence. I used to yearn for this kind of “model minority” citizenship. At school, Asian girls were praised for being polite, mannerable, and studious — juxtaposed against my inherent ostentation. At work, the white man who professed a “preference” for Asian women was praised for being open-minded and “sensitive” — “woke,” even. From Madame Butterfly to Sailor Moon, I saw so much praise for Asian femininity in Western culture that, even in my feminism, I overlooked the dangers in it. Being Black, I dealt with hypersexualization, starting at a very young age. I knew the kind of violence these stereotypes mapped on me, but my harassment often stemmed from the image of my body as undesirable. I learned to strive for “pretty” as a way to offer myself some protection. I hoped the attention Asian women got for being desirable kept them a little bit safe. But I was wrong.

Why, against all evidence to the contrary, are Americans so desperate to believe that people don’t hurt those they desire?

“At any small town bar, white men pivot on their stools towards me, [like] compasses tuned to [my] destruction,” Jane told me as we sat in that October car, the beginnings of an essay. “I try not to wobble in my fear,” she said, “to not see what they see of me, [my] black hair splayed across the ashtray of their fantasies.” For a moment, I was speechless. In truth, I had not fully absorbed how these idealized fantasies of Asian women are just as toxic as any other prejudice.

Why, against all evidence to the contrary, are Americans so desperate to believe that people don’t hurt those they desire? In the recent murder of six Asian women in Atlanta, the shooter’s alleged motive was reported as “eliminating” the source of “temptation” from his “sex addiction.” It is a turn of phrase that makes these women casualties, not targets. It’s an evasion that ignores the fact that the shooter selected massage parlors — vulnerable spaces of sexual marginalization disproportionately inhabited by immigrant women of Asian descent. “Eliminating temptation” by eliminating Asian women is a hate crime.

Hate crimes targeting Asian people increased almost 150% in 2020. Of the nearly 3,800 anti-Asian racist incidents reported over the first year of the pandemic, 68% were against women. Sexualized racism can’t account for all of this violence, but the “pretty” problem encompasses much of it. “Pretty” suggests a person who is docile, compliant, or easy to take advantage of. The same stereotype that makes Asian women objects of desire makes all Asian people susceptible to violence, particularly the elderly. And because we accept this anti-Asian bigotry so widely in Western culture, predators experience almost no accountability for this wave of assault.

At a recent solidarity event, Jane Wong referred to the women who have been assaulted and murdered as her sisters. I appreciate this because, through her friendship, Jane had taught me how to be a better one. In carpentry, “sistering” is the process of repairing something damaged by fortifying it with support. The task is skilled and patient. It is not about covering over the existing trauma so that no one will see it. It is about the tethering and tying together of our respective humanity. Let us all be sisters in our anti-racism — and in our anti-violence. It is our repair work.

This article was originally published on