28

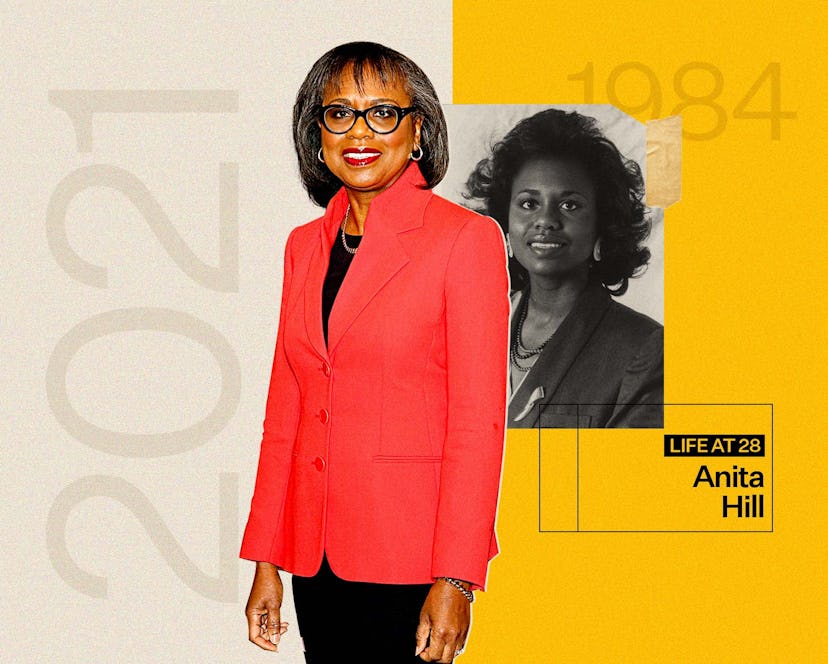

At 28, Anita Hill Found A “Safer” Space To Live & Work

The author and educator talks about her reasons for leaving Washington, D.C.

In Bustle’s Q&A series 28, successful women describe exactly what their lives looked like when they were 28 — what they wore, where they worked, what stressed them out most, and what, if anything, they would do differently. This week, Anita Hill looks back on leaving Washington, D.C.

Iconic isn’t a descriptor I use lightly, but for the past few weeks since our interview, I’ve failed to find a better word to describe Anita Hill. During my decade as a journalist, I’ve talked with Fortune 500 CEOs, people steering culture, and even Warren Buffett. Hill’s lifework falls into an entirely different tier of impact. It takes an unwavering resilience to turn the most painful moments of your early professional career — ones rehashed, dissected, and critiqued by strangers across the globe — into a national, policy-changing movement. Yet for the past 30 years, Hill has done just that.

Her 1991 testimony that Clarence Thomas, then a Supreme Court nominee, made overt sexual comments and advances while he was her boss at both the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) prompted a national reckoning about workplace harassment: Shortly after, the testimony arguably forced President George W. Bush’s hand in signing the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which allowed employees who sued their employers for discrimination to demand a trial by jury and collect compensatory and punitive damages. A year later, harassment complaints filed with the EEOC were up 50%.

But in 1984, at age 28, Hill was far from a household name. She’d just left her role working for Thomas at the EEOC and moved to her home state of Oklahoma. “It was a bit of a weird, strange time for me,” says Hill, who’s now 65 and a professor at Brandeis University. The youngest of 13 siblings, she traded a vibrant Beltway social life for wholesome hangs with family. “I really felt like I settled down. Not ‘settled,’ but that I settled down in a positive way,” she says. Hill had just started her career as a professor, first at Oral Roberts University and then at the University of Oklahoma, with her eyes set on getting tenure. (And in 1989, she did just that, becoming the first African American woman to do so at the University of Oklahoma College of Law.) She was looking and moving forward. “I didn’t talk about [Thomas]. That was part of the problem,” Hill says. “I wasn’t meeting new colleagues and talking about being harassed. I was not as open.”

Since then, she's made it her professional mission to talk about such things in the name of societal change. Her new book, Believing: Our Thirty-Year Journey to End Gender Violence, details how America’s relationship with gender-based violence has morphed in the years after her SCOTUS testimony, with research that comes from a career in the trenches. Hill caps her analysis with actionable suggestions to squash it outright, including a call to action for President Biden to more directly address this massive issue plaguing our country.

“You cannot let the people who aren't comfortable with your authority decide whether or not you have it.”

She talks with Bustle about leaving Capitol Hill, students who doubted her, and the moving goal posts of justice. Iconic, right?

What did a typical day in your life look like when you were 28?

I was going through a transition. I was out of Washington, D.C., and glad to be out. Life was entirely different in Washington, D.C. It was a lot of activity, and all of it focused, maybe too much, on what was going on on Capitol Hill. But Washington was a great place to be a young person who was from someplace else, because just about everybody I met was not from Washington.

Oklahoma was a very different experience. I was back with my family. I really valued that after being young and single and going out. That also gave me a chance to focus on my career in a much more relaxed [and] focused way, to get what I wanted, which was eventually a tenured position teaching law. I could sit down, concentrate on my work, concentrate on my family. In a lot of ways, it felt safer. That was really what I needed.

What do you most remember about your career that year?

I was all in for teaching law. I really felt like that was what I was going to be doing for the rest of my life. You know, teaching [has] a steep learning curve. Initially it was intimidating and baffling. I was in a classroom of people who had probably never had a Black woman making decisions about their futures. I experienced some resistance to my authority and qualification to be a teacher, not only from men, but also from women. You decide, "Is this important to me?" And you realize that you cannot let the people who aren't comfortable with your authority decide whether or not you have it.

What was the most surprising thing you learned about yourself at 28?

I became more confident. I mean, anytime you take on something entirely new, there's a certain level of humility you ought to have. There were times when I thought, "Is this right? Am I the person to do this job?" [But] I had a record of being successful in different spaces.

Did you stay in touch with your D.C. cohort?

That's one thing I do regret. People I spent time with every day or week, I just didn't see. Maybe I'd pick up the phone, or we'd try to stay in touch, but no. When you move on, and you've got different kinds of commitments, and different people surrounding you, you lose track of those connections.

Many people were very surprised when I left. When I left Washington, [during] my last week, there were some days when I had two lunches, because I was spending time with people I wanted to say goodbye to. A couple of friends [threw] a surprise birthday/going away party. It was the only time in my life I've ever had a surprise party. That felt good.

You always think, "OK, these are the best people in the world. I'm going to be with them forever." But there was no email. No social media. I mean, we didn't have cellphones. So it was entirely different. But I made new friends in Oklahoma, and spent time with my family. That made up for some of the loss.

What advice would you give yourself at that age?

Patience. To understand that wherever you are, that you're in it for the long haul. That things don't necessarily happen overnight. And don't get frustrated if they take longer than you think they're going to take.

When I was 27, 28, I thought things like race discrimination, which is where I was focused, and gender discrimination would be solved in the short term. I had siblings who were much older, who had grown up with segregation. I had grown up in an integrated society. I thought we were on the verge of changing society. I thought getting to equality was going to be a sprint. Over time, I thought, "Well, it's not a sprint. It's actually more of a marathon.”

Now, at 65, I think of it as a relay. You know, we’re on this planet, and we do the best we can to get to a more just and fair society, and then we pass the baton to another generation. Because the concepts are always evolving, and we're always learning more about what true equality is, and what true justice is.

With that in mind, how would your younger self view the recent rise in hate crimes and gender violence?

I absolutely think my 28-year-old self would be very distressed and discouraged. But I also think that there was a fighter in that 28-year-old that continues today. I say discouraged, but not so much that she would quit. Maybe she would just fight harder.

What would your 28-year-old self think of who you’ve become?

She would be completely shocked. I never would’ve thought I’d be writing a book about 30 years of hearing from victims and survivors about gender-based violence. That was not on my radar. I never thought I’d be the subject of a public conversation about sexual harassment. So she would be [like], "Wow, didn't see that coming."

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.