Books

How Gratitude Lists Help Poet Yrsa Daley-Ward Keep Negative Feelings At Bay

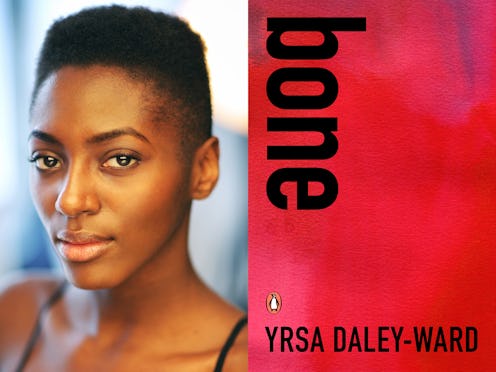

Poets, typically, are known for being a lot of things. Brooding. Contemplative. Deep. Perhaps a little tortured. I love poets — I love their minds and their words, their bravery and their willingness to hold difficult emotional spaces. But rarely do I find myself thinking: my, what a contagiously joyful poet this is. Yrsa Daley-Ward, author of the collection bone, re-released as an expanded edition from Penguin Random House on September 26, is a contagiously joyful poet — outwardly in love with the work that she’s doing and the poetry she’s writing.

Readers love her too. She’s assembled over 121,000 dedicated followers on Instagram alone, tens of thousands more across all her social media platforms, where she shares excerpts of her work alongside photos of her and plenty of fan reposts of her book. bone, Daley-Ward’s debut collection of autobiographical poetry, was first self-published in 2014, selling over 20,000 copies before being re-released by Penguin as an expanded edition this fall. This latest printing includes 40 pages of new, previously unpublished work, navigating — as the entire collection does — themes of racism, sexism, gender, sexual identity, womanhood, the pains of preadolescence, religion, and so much more.

Bone by Yrsa Daley-Ward, $10, Amazon

Daley-Ward spoke with Bustle shortly after the re-release of bone, sharing her writing process, her tricks for staying grounded and inspired, and giving us a head’s up on what readers can expect from her next.

“I was raised on poetry,” Daley-Ward tells Bustle. “I was raised in a really religious household, but even Biblical verses are poetry. I was also raised on Roald Dahl and writers like that, and the lyricism of song as well, and that lyricism has influenced me. I think poetry writing connects with the reader really succinctly — with whatever feeling, whatever emotion. That’s what draws me to it, because you can make that connection in a very short amount of space and time.”

It’s clear from bone that Daley-Ward writes with an eye for that connection — she’s known for spare, direct, and accessible verse; beautiful but succinct. It’s this style, and the poet’s unguarded authenticity, that keep readers coming back to Daley-Ward, time and time again. “I’m quite intuition-led,” she says. “There aren’t many things I wouldn’t tackle in writing. I’m a quiet person in everyday life and I don’t say everything that I think. But when I write it’s my complete space for wildness and freedom.”

bone reads as a very freeing text. Though Daley-Ward navigates social, cultural, political, and personal struggles that could easily lead to darker, heavier verse, her poems have a distinct sense of play to them — as though she's enjoying the process of constructing small stories, playing with words, arranging her text, experimenting language. When I ask her about this she enthusiastically agrees.

“Yes, because that’s me!” she says. “Although bone does talk about a lot of things that are perhaps considered more difficult to handle, some truths that are harsh, things that happened that were not enjoyable at the time, I don’t personally connect with trauma in that way. I don’t hold on to it. There are ways that we can look back on things that have happened that can make us laugh — struggles that can actually be beneficial in the long run because of the richness of the experience. I don’t believe in just one way of looking at things that seem negative. I haven’t really had a simple life — if any life can be simple. So there’s lots to write about. And it’s wonderful, that I can reach into that.”

I ask Daley-Ward if it was difficult to return to bone for Penguin’s re-release, two years after the original collection was self-published — if she finds re-reading her own work difficult, or if there were things she was eager to change in the expanded edition. There wasn’t much.

“I try to approach my work without judgment,” she says. “Of course when I looked through it I first thought there were so many things I really would change. But then, when I had the opportunity to change things, apart from what was glaringly obvious, like typos, it just did not make sense to change it. I know it’s written from a snapshot in time, and I have to be as true to that moment as possible. I did have all those ordinary feelings of: “oh, why did I write it like that?” But it was for a reason. I do trust in the original thought process.”

It’s a writing process that comes from equal parts intuition and ritual. When I ask Daley-Ward how she prepares to sit down and write, two things come to the poet’s mind: dreams and gratitude journaling.

“After you’ve been close to that dream space, you wake up with this open mind and open heart. It’s another layer of consciousness that you don’t really edit, you don’t critique. Strange things happen in dreams, things that are just beyond the everyday filter that we have. So when I wake up in the morning is the absolute best time to write, because I don’t edit myself. I’m just quite brave in the early hours of the morning.”

Composing gratitude lists is something else the writer describes doing nearly every day — a ritual separate from her poetry, but that lays the foundation for her writing time. “It actually frees my mind space up so I can write,” she explains. “It’s all connected. The gratitude lists keep negative feelings at bay, and negative feelings or depression can be a huge block for any writer. That ritual helps me to think in a different way, to keep my mind and my energy clear.”

As a poet who has shared her work extensively on Instagram, Daley-Ward has been compared to (and shelved alongside) some of the other great Instagram poets writing today: Rupi Kaur, Nayyirah Waheed, Lang Leav. I ask her about her experience sharing her work with 121,000-plus readers with a single click—what inspires her to share her work in this way, what challenges it might pose, and if she thinks social media is changing the way poets write and readers consume poetry.

“I started sharing on Instagram at a time when it wasn’t as prevalent as it is now, and I realized it’s such a beautiful way of disseminating poetry,” she says. “A lot of lines in poems stand alone, and we’re living in a day and age when people don’t perhaps spend as much time with the written word. But nearly everybody has as smart phone and just getting two lines of something that really resonates with you — on your way to work or something like that — can really change your day. Maybe you send it to someone else, you use it to say something that you’d wanted to say yourself. I really admire that. I saw these pieces starting to pop up and I thought: that’s what I want to do. I just find it a really beautiful, modern way to share literature. It’s human emotion — and you can’t really run away from things that are of the heart.”

She’s also noticed a shift in readership that she finds exciting. “I was one of those people who did not want to read classic poetry in school — it was boring! I mean sure, some classic poetry is beautiful, but the whole of it wasn’t associated with anything that was happening now. But what I love, with the internet, is that there are teenagers, people younger than teenagers, who are connecting with words and language and wanting to go out and buy books of poetry. It was once thought that poetry was dead, which was really sad. But it’s gone through this huge change and now there is this modern cannon of writers who are just killing it.”

As far as what readers can look forward to next? (I know you’ve all been wondering.)

“I have a memoir coming out next year called The Terrible,” says Daley-Ward. “It is very, very autobiographical. It goes even further [than bone] and I’m so excited about that. Along with bone it’s the truest thing I’ve ever written and I’m really looking forward to it being out there. I let myself go a little wild while writing it. It’s memoir so it’s not all easy — having to recall things you’ve long forgotten and bring them back. There were times I’d have to force myself to the table to write, and there are some not-so-fun parts of it. But all-in-all it’s a blessing, doing what I consider to be my life’s passion.”