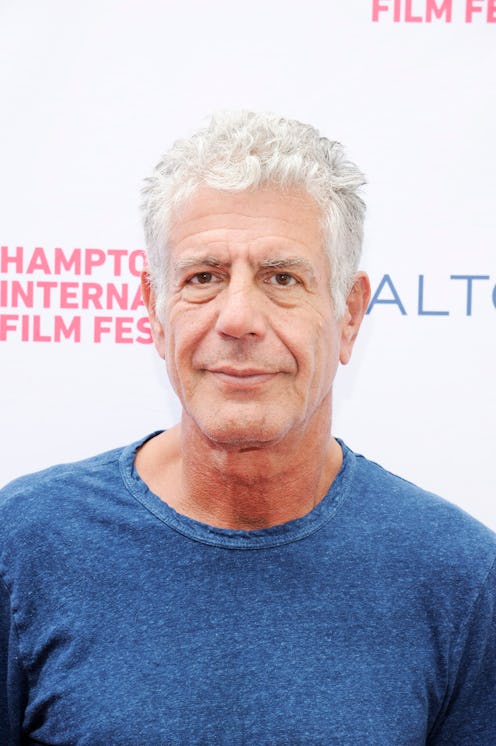

My family invited Anthony Bourdain into our home every week, and every week he took us around the world to places we'd never have a chance to experience without him, introducing us to various cultures, talking to different people, and exploring a variety of foods that both enticed us and made this vast world seem a little smaller; connected; more easily understood. So on Friday morning, when news broke that Anthony Bourdain died by suicide in France while filming his award-winning CNN series Parts Unknown, I felt as though I had lost a dear friend. Again.

Warning: This article contains information about suicide, which some may find triggering.

Bourdain was more than just a celebrity chef, critically acclaimed author, and television show host: he was an equalizer. On every episode of Parts Unknown he took viewers to places both near and far, and made us feel connected to people we have never, and probably will never, meet — all via a love of and curiosity for food. He was a conduit for our shared humanity; a personified representation of the things that bind us all, no matter where we live or what languages we speak or, yes, the kind of food we eat.

So it only makes sense that Bourdain made me feel connected to my dear friend and the first man I had ever loved — admittedly, when I was young and the idea of love was as romanticized as it was fleeting. Seven years ago, my friend died by suicide, too.

Bourdain was a lot like my friend: crass, unapologetic, rough around the edges but undeniably kind, especially to those who knew him best. Christiane Amanpour, who called Bourdain a "friend, collaborator, and family" on Twitter, described him as, "A huge personality, a giant talent, a unique voice, and deeply, deeply human." To many my friend was standoffish, but to me he was tender, thoughtful, and forever willing to help the people he loved.

My dear friend was also misunderstood by those who didn't know him, much like Bourdain at the start of his career. Described as a "sadistic chef," and one who has been open about his drug and alcohol abuse, Bourdain changed what we all envision when we think of a world-renown chef. A man "not always respected in the kitchen," I imagine Bourdain walking behind the line with the same demeanor of the middle school stranger-turned-friend-turned-boyfriend-turned-more than a friend I struggled to described: confident yet unsure, with an "I don't give a fuck" attitude masking a raw vulnerability that, once acknowledged, was impossible to ignore.

And, like Bourdain, from time to time my friend's actions were problematic in ways that were representative of the time, location, and culture he was living in. In 2017, and in the wake of the #MeToo movement and sexual assault allegations against Mario Batali and Ken Friedman, Bourdain wrote in an essay published on Medium:

"To the extent which my work in Kitchen Confidential celebrated or prolonged a culture that allowed the kind of grotesque behaviors we’re hearing about all too frequently is something I think about daily, with real remorse."

Bourdain wasn't perfect, and he was quick to admit it. He knew what he didn't know, then did the work to try and educate himself and, in the process, others. My friend wasn't perfect either, though I often remember him in a way that eradicates the very imperfections that drew me to him.

And, like Bourdain, when my friend died I felt like I didn't really know him at all. Time had moved us forward, through the growing pains of middle school and the confusion of high school and to separate paths that took us separate places. He stayed in our small town, while I left the state to attend college. He started a family, and I started working on my career. Over the years we would run into one another, but never at what we described as the "right time." I was in a relationship, and he was single. I was single, and he was in a relationship. We were both single, but I was living thousands of miles away. We became distant friends in love with an idea of us that would never manifest, holding onto a childhood love that grew with us but couldn't materialize. A love we both knew still existed.

We had just started reconnecting — just started getting to know one another again; the new, evolved versions of our younger selves — when my friend died. And in so many ways, even though Anthony Bourdain was 61, it felt as if the world was just starting to get to know the real, evolved Anthony Bourdain, too.

The death of Anthony Bourdain feels like the death of a connection to a friend I know I won't see again. Like time is taking away another reminder that a red-headed man with an infectious smile and a big heart lived, and loved, and changed my life in ways both big and small. But unlike the old flip phone I still keep in a drawer, with the last text messages my friend sent me, this reminder is a human being with friends and a family. He has a daughter. He is a victim of rising suicide rates we, as a culture, seem hellbent on ignoring. A report was released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that showed the suicide rate is up more than 25 percent since 1999. In 2015, 45,000 people died by suicide.

Suicide impacts us all, whether we intimately knew the individual lost or not. To downplay that undeniable fact by positioning celebrity as some kind of "disconnect from reality" is to strip us of our humanity; of the connections we inherently have with one another.

So today I mourn a man I knew, and a man I didn't. Because, in a way, I loved them both just the same.

If you or someone you know are experiencing suicidal thoughts, call 911, or call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741. You can find more resources about suicide prevention at the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.