Books

Why Are So Many Women Obsessed With Thrillers?

It’s Friday night. Finally. The smell of dinner still lingers in the air. The sun has barely gone down, and I’m in bed. I pull the blanket over my head so just the light from my Kindle screen glows around me. I’ve been waiting for this moment all week, ever since I started reading Underdog, the latest suspense novel by indie author Kristen Mae. My breath fogs up the screen and I can’t swipe fast enough to cut the tension. My phone rings at exactly the moment the main character’s phone startles him in the book, and I nearly fall out of the bed. I answer.

My cheeks heat as I attempt to explain my choice of Friday night activity. The Kindle is laying face-up at the foot of the bed, the cover art glowing in the dim light. A pair of dark eyes stare back at me from behind a man’s glasses, and I shiver. It’s just a story, right? Granted, it’s a story about a young writer who is accidentally abducted by her biggest fan and kept hostage in his basement because he’s secretly in love with her. As a women — and a writer — that doesn’t scare me, I tell my friend over the phone. OK, it does, but that’s why I like it.

Women writers have more power than ever before, and the #MeToo movement is breaking down the barriers of rape culture. So why are female writers still telling stories about women being hurt?

I hang up the phone, bemused. I look over at my night stand, piled high with best-selling thrillers. Their covers are adorned with the frightened faces of women, dripping blood, and enticing captions with adjectives like "heart-stopping," "breath-taking," and "captivating." Story after story about women being kidnapped, held against their will, physically and psychologically confined. And each and every one of them are written by women.

Is there something wrong with me? Am I a bad feminist?

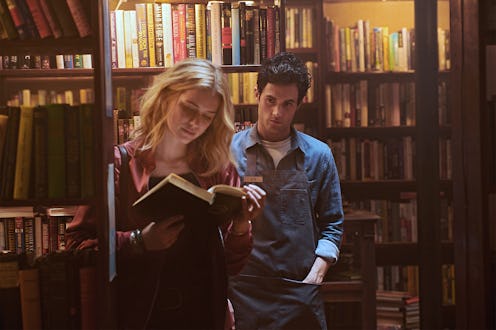

It’s not just me. Over the last decade the suspense and thriller bestsellers lists have been adorned with the likes of Room by Emma Donoghue, Then She Was Gone by Lisa Jewell, and You by Caroline Kepnes. (Both Room and You were adapted for the screen, as well.) The kidnappers, stalkers, and jilted lovers mentioned on back cover blurbs tempt me and hundreds of thousands of other readers. Women writers have more power than ever before, and the #MeToo movement is breaking down the barriers of rape culture. So why are female writers still telling stories about women being hurt?

Turns out, I’m not a bad feminist at all for wanting to read these stories. It’s actually quite the opposite.

Take Emma Donoghue’s heroine in Room: She survived, captive in a one-room dungeon for years, slept beside her abductor, carried and nurtured his child, and yet her spirit still cannot be broken. In fact, it’s exactly the same maternal instincts that keep her compliant for the safety of her child that also drive her to eventually fight back. Sounds almost empowering, doesn’t it?

A recent article by Jessica Barry in Crime Reads suggests that women enjoy reading thrillers in which other women are the victims not because they are sadists or anti-feminist, but rather because it offers them a form of redemption. “The narrative is not — or at least not only, and not always — that bad things happen to women," Barry writes. "It’s that women have the ability to survive when bad things happen." These thrillers offer readers the voyeuristic thrill of watching a woman defy the odds and triumph despite being threatened, tortured, and culturally pigeon-holed. Scary.

Research suggests that most people love to be scared, at least a little bit. When someone reads something that scares them, their brains release a chemical called dopamine which is part of the body’s fight or flight response. However, when they trigger this reaction in a safe, controlled environment — like their home, while watching a movie or reading a thriller — they give their brains a chance to process those kinds of feelings without any "real" danger. In a sense, they are practicing defeating their fears over and over. The more they train their brains to recognize and process that feeling of familiarity and fear, the less overwhelming it feels.

Writers are often told "to write what you know," and most women know the fear of being relentlessly pursued.

The lead in the Kristen Mae book I’m reading, Addison, is a young writer whose story has caught the attention of a smitten male reader. Being stalked is a fear of many women, and it’s not much of a leap to assume that many female writers will relate to Mae’s heroine. Writers are often told "to write what you know," and most women know the fear of being relentlessly pursued. That's what drew me to Kristen Mae's story, as a writer and as a woman: It could be real. It could be me. It’s because it scares me that I need to know how it ends for Addison.

Fear can actually be a culturally-driven, dynamic experience. A 2016 article in Vox tracked the increasing popularity of horror movies about invasion and linked it to the right-wing fear of foreigners. Whether you support a xenophobic and racist government or not, it’s impossible not to be bombarded on a daily basis by the concept of this fear via news outlets and social media feeds.

So why the recent trend toward stories about possession and confinement of women? Precisely because it’s the thing that scares so many women.

Women are by far the most likely victims of abduction and domestic violence. (According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, one in four women have been victims of severe physical violence by an intimate partner.) Most women are not abducted by stalkers, held captive in an underground bunker, and forced to fake affection for their abusers, as happens to Addison in Mae's book. But the reality is not far enough away for comfort. Many women walk home at night with pepper spray clenched in their fists, wake up in cold sweats in the middle of the night worrying that they might have forgotten to lock their front doors, and refuse to accept drinks at a bar for fear of being drugged. Fear is part of the culture and identity of womanhood.

Women writing about and wanting to read stories about other women being abducted, confined, and ultimately liberating themselves represents a cultural swing away from traditional patriarchal society and misogynistic oppression. Research on the psychology of fear suggests that humans fear what they are taught is negative. This suggests a societal awakening: Things women accepted as inevitable can in fact be overcome.

Women don’t need to be saved by men. Women can save themselves, even if it’s just from the safety of their homes on a Friday night, covers drawn over their heads, and a stack of new foes to defeat on their nightstands.

And as I return to the safety of my bed, discarded Kindle returned to its rightful place beside me beneath the covers, it occurs to me that I’ve read versions of Mae’s Underdog before. A beautiful young girl, admired from afar by a man who believes himself inferior of her voluntary affection, takes her against her will. It’s John Fowles’ The Collector all over again. Only this time it’s written by a woman for women. I don’t need to deny my fear in order to be strong. I can embrace it, wrap it around me like a cloak in the night, and prove over and over that what doesn’t kill me only makes me stronger. I own that fear.

This article was originally published on