Books

Who Owns Harry Potter? What J.K. Rowling's Series Can Teach Us About Copyright Law

It was summertime in Georgia when Chels Harvey discovered fan fiction. Harvey, then 10 years old, was spending the season cooped up at home while their mother worked. On one lazy afternoon, as their brother digitally tromped through Neopets.com, gathering Neopoints and playing flash games, Harvey was drawn to the site's boards, which functioned as rudimentary chat rooms.

"I was fascinated by the ability to communicate with strangers," Harvey tells Bustle. Harvey began "role-playing," messaging back and forth with other users, 250 characters at a time, to build a collective, long-form story. They published within the Harry Potter thread for several years before being introduced to MuggleNet.com: an entire website dedicated exclusively to Harry Potter role-playing and fanfic. And it was just like John Green's description of falling in love: "slowly and then all at once."

"I had read the Harry Potter books as they'd come out, but I'll admit I sort of lost interest in them when I realized I could work with other people, strangers, from across the world — inventing our own," says Harvey. "There was no magic greater than that."

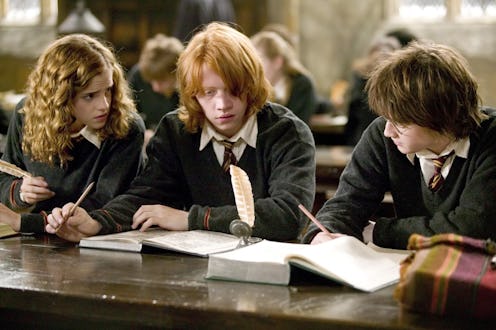

It's a common experience within the fan fiction community — the love of a canon's fanfic eclipsing, at least a little bit, the original work. The characters become people. But despite the deeply intimate connection many have with Hermione and Ron and Harry, they are, ultimately, characters. They are intellectual property, and they belong to someone. So who owns Harry Potter? For the thousands of superfans across the world who gather on online platforms like fanfiction.net to write their own stories within established literary canons, it's a question not often considered, at least not deeply. Sure, legally, Harry Potter is a creative entity. But for an entire generation, he and his peers are culturally ubiquitous. They're above the law, or at least, outside of it — right?

Uh, not... really...

"I sort of lost interest in them when I realized I could work with other people, strangers, from across the world — inventing our own," says Harvey. "There was no magic greater than that."

At the base of our current set of intellectual property and copyright laws is the Copyright Act of 1976. Joshua Bressler, a New York-based copyright lawyer, tells Bustle that at the heart of the Act was the belief creators' fruits of labor needed to be protected.

Culture is better, is more inclusive, is more dynamic (not to mention enjoyable) when the arts are thriving. Copyright law, says Bressler, incentivizes creativity. Reduce it to a tangible form, exhibit a "modicum of creativity," and you own the rights. A greeting card you write to your aunt is copyrighted, he says.

"Culture is better, is more inclusive, is more dynamic (not to mention enjoyable) when the arts are thriving. Copyright law, says Bressler, incentivizes creativity."

So how, then, does something like Saturday Night Live exist, like, at all? There are several key elements to copyright law that make it amenable to human nature because, as we all know, culture is built on borrowing and building and growing.

The first is that parody and satire is protected and needs no permission from the original owner. You can borrow heavily from the original — MAD Magazine is a great example — and remain, essentially, untouchable. It's a form of creation that is protected as "fair use" (another key idea) due to its "transformative" nature. "Fair use" is, understandably, a deeply individualistic law. Often times, Bressler says, we don't know whether a situation involves fair use until the courts say so.

But fan fiction? Legally, in the strictest sense, it doesn't matter whether you profit off your work, and it doesn't matter your ultimate intentions — if you're publishing a work online, without any indication that it's not affiliated with the original work, it's technically copyright infringement, says Bressler.

In 2004, on the eve of the third Harry Potter movie release, Rowling gave her blessing for fan fiction in a statement from her literary agent, along with three stipulations: that fan fiction endeavors remained non-commercial, that the stories continue to exist online (and not in print) and, well, that the stories not be, uh, obscene. "She is very flattered by the fact there is such great interest in her Harry Potter series and that people take the time to write their own stories," a spokesman for the Christopher Little Agency told BBC News at the time. "The books may be getting older, but they are still aimed at young children. If young children were to stumble on Harry Potter in an X-rated story, that would be a problem."

Rowling, true to her word, has continued to allow Harry Potter fan fiction communities to flourish, so long as they abide by her rules (In 2011, Rowling's team of lawyers sued the author of The Harry Potter Lexicon — and won). This tactic, to allow a wide berth when it comes to copyright, has become increasingly common among owners of popular franchises.

"Irrespective of what the law tells you, some property owners have very evolved thinking about fan fiction," says Bressler. "They cannot divert their legal resources or they’ve been stung, so they publish guidelines."

"Irrespective of what the law tells you, some property owners have very evolved thinking about fan fiction," says Bressler.

Paramount, for example, which owns the rights to the Star Trek franchise, has an entire section on its website about fan fiction film guidelines.

The moral of the story? Check for the guidelines, says Bressler. If there are no officially stated parameters, be clear about your lack of affiliation with the original source and that you in no way are sponsored by them.

Still, for the legions of fan fiction writers, their online communities bypass copyright, if not legally, then culturally. Spiritually, almost.

"All anyone wants to do is communicate using a shared experience — that's all fan fiction is. Taking something we love, and expanding it with new ideas from diverse perspectives who otherwise aren't given a voice," says Harvey. "I was 12 years old, writing fan fiction about Percy Weasley figuring out he was queer during a summer internship at the Ministry of Magic. Online role-playing boards and fan fiction archives were like the digital open mic for my 12-year-old, homebound brain."