I got the call on July 7 that Olivier, my husband, just 50 years old, had passed away from a heart attack. It was, according to his daughter, quick and painless, as one would hope a death will be, and she commented on how peaceful he looked, lifeless in the hospital bed.

My initial response was to laugh; this has been my response to the few other death announcements in my life. It wasn’t that I was happy or delighting in what I’d been told, but it was incomprehensible, and the disbelief could only come out as laughter. But I held in that initial response that day and accused her of lying instead.

When my husband passed away, we had been separated for a year and a half. The demise of our relationship wasn’t unlike any other demise — he cheated on me with someone 28 years younger than him, a woman who would send me a poem about her love for my husband shortly after I had uncovered the truth on my own. I, in turn, would retaliate by sending him horse manure because, at the time, it seemed like the most appropriate way to handle things. What followed, for the next several months, were two angry people who passed blame, hateful words, and promised to never forgive each other.

But in January of this year, I forgave him. I had to forgive him for my own sanity. I had tried everything — traveling, diving with sharks, going on safaris, looking for spiritual guidance from monks in Cambodia, even setting up a Voodoo altar, but nothing worked. Forgiveness was my only freedom.

We were separated, he had cheated, so who the hell was I to mourn him?

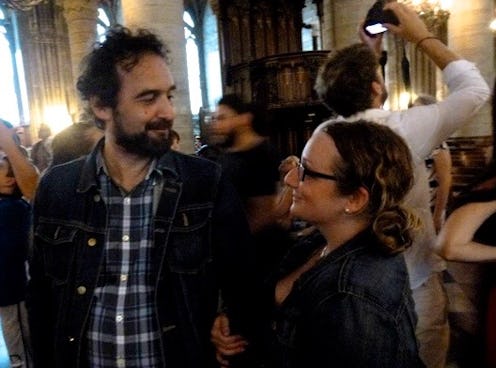

But when he died, the fact that I had forgiven him or that we had become friends or that we had ever been in love at all didn’t matter. We were separated, he had cheated, so who the hell was I to mourn him? To say our relationship was complicated, would be an understatement, but all relationships are complicated. We had put each other through the ringer and come out the other side. We were texting almost daily, talking on the phone weekly, and even wondered if maybe we weren’t done with each other; if maybe some day down the road we’d make more sense than we did now, and when that happened, if that happened, we’d grow old together on that porch like we had imagined when we were newly, and so deeply in love with each other. We even had plans to have dinner on the day that would end up being his funeral.

Instead of laughing with him over glasses of red wine and confit de canard in our favorite brasserie in Montmartre as we had planned, I sat in an apartment in Pigalle alone on that day. I wasn’t “welcome” at the funeral. It had been decided by his mistress that I was not allowed to mourn. I wasn’t even told where he was buried by his family; I had to find out from a mutual friend.

I wondered if he had told her that we had decided to stay married, figuring it made more sense than to get divorced. I wondered if she knew that we had decided to never get off the phone without telling each other that we loved each other, or how we promised each other to never allow hate to grow between us again. Maybe she knew and my being unwelcome to the funeral was out of spite. Or maybe she never knew at all. Or maybe it just didn’t matter to her or his family. Perhaps all they saw or understood was that I was his past, things had been messy, and in being part of that messy past, I was automatically stripped of my allowance to grieve.

But it wasn’t just his family who felt I didn’t have a right to grieve. Even in conversations with some friends, it was rarely about how I was grieving, but whether or not I had the right to grieve, with one friend shrugging off his death the way one shrugs off bad weather: “Sh*t happens,” she said. Another suggested his death was karma for having cheated on me, while a handful more questioned my devastation. We had, after all, been separated. The concept that I could have still loved him, and therefore carried the weight of a broken heart after his death, was something that was lost on some people. It simply didn’t make sense to them. Then there were those who wondered if I was grieving too much or not enough. Why was there a photo of me on Instagram smiling? Shouldn’t I be in bed grieving? What do you mean you’re not coming to my wedding? Aren’t you done grieving yet?

Grief is a funny thing. Not “haha” funny, but perplexing funny. While death remains a taboo subject and one that makes people awkward, grief doesn’t have the same effect. Grief, because it doesn’t always have to accompany death, seems more up for debate or judgment. While the word “death” might be whispered across a dinner table, the word “grief” is not. People seem to think they have a stake in the grief that someone else is experiencing — or not experiencing — and aren’t shy to say so.

When Patton Oswalt announced his engagement earlier this year, strangers took to Twitter to question whether or not he had grieved long enough after the death of his wife. Had he properly paid his dues to the grief gods before he dared to move on with his life? Had he shed all the tears that one human can shed in a lifetime before thinking it was appropriate to find happiness again? I mean, that's what you have to do, you know, before you're allowed to get up off the floor, where you've been laying in your sadness, and face life again — at least this is what some would have us think.

A man I love is gone. It's not more complicated than that.

I don’t need to be reminded by friends or family of all the times I wished Olivier dead. I clearly remember every single one. I recall being on my knees inside Sacré-Cœur early one morning, praying to the God in whom I don’t believe that Olivier would die. To know that he was out there living his life, after what he had done to me, wasn’t just unfair in my mind but a true injustice. I was blinded by rage and humiliation. But during all those months of wishing and praying, I had never really imagined a world where Olivier wasn’t alive. I had thought about taking away his laughter as punishment for his actions, but never considered what it would mean to never hear that laughter again. I know now it’s because I couldn’t fathom such a loss. Even in my anger, such a silence wasn’t tangible. I wasn’t going to lose him, so I would never know what it was like to grieve him. Or, as the case would be, have my right to grieve be up for debate.

It's been a little over four months since Olivier’s passing. I have lost friends who, although knowing Olivier and I when we were together, and having witnessed our love, were all but offended that I grieved a man who, in their mind, didn’t deserve my grief. I’ve also learned to not put stock in these opinions. I do not owe anyone an explanation nor should I concern myself with trying to come up with explanations. A man I love is gone. It's not more complicated than that. And, contrary to the input of those around me, I will grieve or not grieve however I choose.