News

What Black Women Running For Office Are Up Against

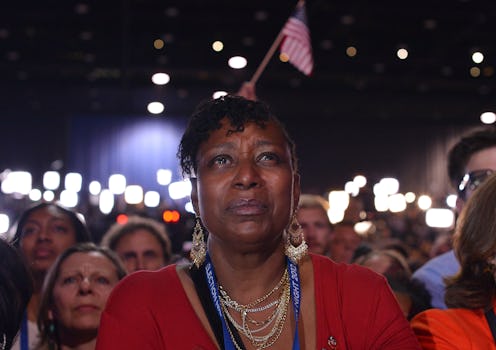

“African-American women are the backbone of the Democratic Party,” an ecstatic Tom Perez, chair of the Democratic National Committee, said not once, but twice on a press call Wednesday. Perez was stating the undeniable after 98 percent of black women voted for Doug Jones in Tuesday’s special election, overcoming systemic barriers to make Jones the first Democrat in 25 years to win a U.S. Senate seat in Alabama.

Black women's widespread support for Democratic candidates is not new. In the recent governor’s race in Virginia, 91 percent of black women backed Democrat Ralph Northam. Last year, 94 percent of black women voted for Hillary Clinton. But based on the astonished reactions and exuberant expressions of gratitude from commenters on social media, you would think black women had only just materialized in Montgomery this past Tuesday.

“Dec. 12, 2017: the day progressives discovered black women,” Jessica Byrd, founder and principal of Three Point Strategies, a consulting firm focused on electoral politics and social justice, says with a laugh.

On Twitter, as many praised black women for delivering Jones the election, the conversation quickly turned to how that gratitude should translate into greater support for black women in all aspects of their lives.

“Thank black women by supporting black women,” writer and speaker Austin Channing tweeted. “Pay us. Vote with us. Hire us. Read our writing. Fund our projects and ministries. Vote us into office. Purchase from our businesses. Amplify us. Stand against racism and sexism.”

Take the “vote us into office” part: The numbers show that black women’s participation at the ballot box is not reflected in their representation in elected office. Black women were 7 percent of the electorate in 2016, but they make up only 3.6 percent of all members of Congress, and 3.7 percent of all state legislators.

“The investment is not matching their return,” says Kimberly Peeler-Allen, co-founder of Higher Heights, a national organization building the political power and leadership of black women.

The Primaries Are The Problem

While there are multiple barriers to black women running for office, the biggest challenge is the primary process. By the numbers, a black woman candidate’s best shot at winning a race for public office is in a Democratic stronghold. And to compete, she must engage in a primary. “And what do Democrats hate?” Byrd asks rhetorically, “Primaries.”

“Unless someone says ‘I choose black women,’ we’re not going to get chosen.”

In 2015, Byrd was part of a team that did research to understand the racial and gender disparities in office holding. She and her colleagues found a disturbing trend in their interviews with black women who had considered running for office.

“They were told they weren’t viable,” Byrd tells Bustle. “They were told that they didn’t know enough people that other Democratic operatives knew. They were told that they couldn’t raise the money and they weren’t a good investment.”

So, the challenge wasn’t persuading black women to run for office; the challenge was securing institutional support.

“If the party believes that we should lead,” Byrd says of black women, “they have to change the process by which they invest in new types of leaders.” By that, she means something that might seem radical: a willingness to clear the field for black women.

“Unless someone says ‘I choose black women, we’re not going to get chosen,” Byrd adds.

Activists Look Beyond The Party

“Engaging in the political process is not new for black women,” says Charlene Carruthers, the national director of Black Youth Project 100, an activist member-based organization. “What’s also not new is the consistent lack of investment by the Democratic Party, and progressive and liberal funders.”

Amanda Brown Lierman, the DNC’s political and organizing director, admits that there is work to do on that front. “We have to put a lot of effort into rebuilding that trust,” she tells Bustle. “That is part of our job every single day.”

In the past year, the DNC has worked to redefine its mission to include a focus on down-ballot races. The party boasts its investment in InCharge, a black women voter mobilization program. And in Alabama, the committee quietly pumped a million dollars into the state, largely focused on reaching black, faith, and youth voters.

But Carruthers argues that for lasting change to occur, money must continue to flow to black women-led efforts with “locally sourced agendas – transforming criminal justice, the economy, and the way the health care system operates.”

Byrd echoes that sentiment. “Black people deserve an independent political home,” she tells Bustle. “We deserve to write the strategy. We deserve to decide how our money is spent. We deserve leaders who know what it’s like to walk around in a black body.”