Books

Start Reading From The New YA Book That's Sure To Inspire The Young Feminists In Your Life

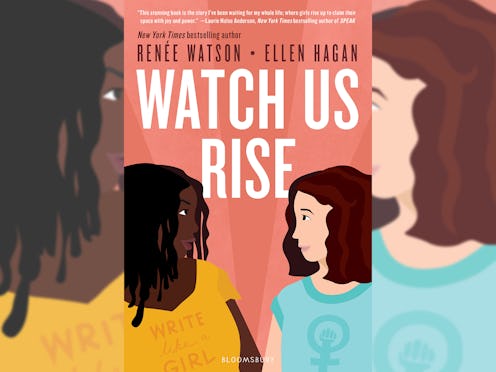

Piecing Me Together author Renée Watson has a new YA novel coming out, and she has co-written it with poet Ellen Hagan, author of Hemisphere. Bustle has an exclusive look at the cover of Watson and Hagan's upcoming book, Watch Us Rise, as well as an excerpt from the novel below. You can get your own copy when Watch Us Rise comes to your favorite bookstore on Feb. 12, 2019.

Watch Us Rise centers on Jasmine and Chelsea: best friends who start a Women's Rights Club at their New York City high school. Their online videos, which document Jasmine's responses to the microaggressions she receives as a black girl, and Chelsea's slam poetry recitations, go viral, attracting both support and trolling. The girls' school principal shuts down the Women's Rights Club when threats escalate against it, leaving Jasmine and Chelsea to come up with new ways to make themselves heard.

Check out the gorgeous cover for Watch Us Rise — and be sure to read Speak author Laurie Halse Anderson's blurb for the YA novel — below, and keep scrolling to get your sneak peek inside Renée Watson and Ellen Hagan's new book, which hits stores on Feb. 12.

Watch Us Rise by Renée Watson and Ellen Hagan, $19, Amazon

Excerpt

The weekend goes by too fast, like always. Monday is dragging. After lunch we’re walking to our classes, and Chelsea keeps complaining about her club. “Jasmine, I’m serious. I don’t want to go back to the All-We-Read-Are-Dead-White-Poets Poetry Club. But there’s no other club I want to be in. What am I going to do? Ms. Hawkins says I have to decide soon.”

“I don’t know, Chelsea, what about Justice by the Numbers? Isn’t it about learning statistics and understanding how those stats impact Washington Heights and other neighborhoods in New York?” I ask. “I think they talk about redlining, gentrification, and—”

“You lost me at statistics,” Chelsea says. “Maybe we can start our own club?”

“We as in . . .”

“Me and you.”

“I’m already in a club!” I say. “Besides, what would our club be about?”

Chelsea shrugs. “Aren’t you tired of dealing with Meg? You could quit the ensemble, and we can do our own thing.”

“I don’t know, Chelsea, what about Justice by the Numbers? Isn’t it about learning statistics and understanding how those stats impact Washington Heights and other neighborhoods in New York?”

We get to my science class and stop at the door. James enters the classroom, and when Chelsea sees him all of a sudden she is no longer interested in a new club. She whispers to me, “James Bradford is in your class? You get to spend an hour with James Bradford every afternoon?”

It is so funny to me that Chelsea says James’s whole name like he is a celebrity or a president, or someone important enough to be called by his full name.

“Why didn’t you tell me James was in your class?”

“I didn’t know you’d care,” I say.

“Well, care is a strong word. I’m just, I don’t know. I didn’t realize you had a class with him too,” Chelsea says.

I give her a look.

“What?”

“Um, does Chelsea Spencer have a crush on someone and isn’t telling me?”

“I, no. We’re just friends—I don’t, I don’t even know if we’re friends. It’s just that I have a class with him, and I didn’t know you two had a class together too. That’s all.”

“If you say so,” I tease.

“Jasmine—”

“Payback for all the comments and jokes you’ve ever made about me and Isaac.”

“Oh, please. You and Isaac are perfect for each other and just need to admit your feelings. James Bradford and I? We barely know each other.”

“If you say so,” I repeat. I go in and sit next to James. Our science class is officially called the Science of Social Justice. Mrs. Curtis is the youngest teacher in the school and is so honest with us that sometimes I wonder if she’s supposed to be telling us everything she does. I had her last year, and I know there is no holding back in this class. We talk about the intersection of ethics, social justice, and science, and sometimes it gets kind of heated.

The units of study this year will be “The Use of Human Subjects in Medical Research,” “The Rising Rates of Childhood Obesity,” and “The Environment, Climate Change, and Racism.”

Mrs. Curtis is the youngest teacher in the school and is so honest with us that sometimes I wonder if she’s supposed to be telling us everything she does.

I’m excited to talk about all of these except the one about obesity. I hate talking about weight with skinny people. As a big girl it’s like I’m invisible around skinny people, sometimes they make jokes or say things like “Oh my God I’m getting so fat,” when really they wear a size small or medium, and no one who wears a small or medium — or large, for that matter — is truly fat. They don’t know anything about being this big. And really, that’s not what bothers me. What hurts is the disgust in their voice, the visceral fear in their tone, like gaining weight would be the absolute worst thing to happen to them. And so I just sit there, kind of in shock for most of those conversations.

It’s completely opposite when I’m the only black girl in a conversation. If race comes up, people look to me to answer questions like I know everything there is to know about blackness. So pretty much my whole life is going back and forth from being super visible to invisible.

Mrs. Curtis starts class today saying, “Good afternoon, everyone. We’ve got a lot to cover today. Let’s jump right in. I’d like you to write down four words that describe you. Don’t think too hard about it. First four words that come to mind.”

I write down my words, and when Mrs. Curtis tells us to share our lists with a partner, I am paired with James.

So pretty much my whole life is going back and forth from being super visible to invisible.

He goes first. “Um, I wrote down athletic, outgoing, generous, and then I couldn’t really think of another one.”

“You couldn’t think of a fourth word?”

He laughs. “I don’t really think about myself like that. I mean, who walks around thinking about words to describe themselves? What, you got like twenty words, huh?”

“Just four,” I tell him. But I could have put down twenty. I read my list. “Black, female, activist, actress.”

“Damn.” James leans back in his chair. “Why you and Chelsea always gotta be so deep?”

“What’s deep about me saying I’m a black girl who likes theater and who cares about our world?”

James doesn’t have time to answer—not that he’d have an answer—because Mrs. Curtis says, “I want you to look at each other’s lists and tell one another what you notice,” she says. Then she adds, “And no judgments, just noticings.”

We swap lists. I go first this time. “I notice that you didn’t describe your ethnicity or gender.”

“I notice that you did. You definitely did.”

“No judging,” I remind him.

“I’m not. I’m noticing that you almost always bring up race and gender no matter what the topic is.”

“Well, the topic is to describe myself. So I did.”

James says, “If our yearbook has a category for Most Likely to Start a Revolution, you and Chelsea will be tied.”

I start laughing.

“What’s so funny?” James asks.

“Oh, nothing. I’m just noticing how you keep mentioning Chelsea. Any chance you get, you bring her up.”

Mrs. Curtis stands and calls our attention back to her. “Okay, so how many of you used adjectives that describe your personality?”

James says, “If our yearbook has a category for Most Likely to Start a Revolution, you and Chelsea will be tied.”

Hands go up.

Mrs. Curtis calls on a few students and writes their words on the board: loyal, funny, generous. She asks, “Anyone use words that spoke to a talent you have?”

More hands go up.

She writes athletic, musician, poet, singer on the board.

Then she asks if any of us wrote down words that describe our ethnicity. Not as many hands go up, and the ones that do are all people of color.

Mrs. Curtis sits back in the circle. She gives us another handout. The top says “Science’s Role in the Social Construction of Race.” Mrs. Curtis says, “Even though race—especially in North America—is how humans get categorized, even though it’s what divided our country and sometimes still does, race is a social construct. It’s really true that on the inside we’re not that different, and in this unit we’re going to talk about that.”

When the bell rings, James and I walk out together. He says to me, “I wasn’t talking about Chelsea a lot.”

“And there you go again,” I say.

James laughs. “Okay, you’ve got a point.”

“I get it. She’s an awesome, smart, beautiful person. What’s not to love?”

“Love? Whoa—who said anything about love? Anyway, I’m with Meg.”

“What? Since when?”

“Last week.”

I hope Chelsea meant it when she said she doesn’t like James.

###

Top 10 Feminist Questions by Chelsea Spencer

- Can I be a feminist and still care about luscious lipstick colors, the best blush, and how to wear enough eyeliner to make my eyes POP?

- Can I be a feminist and still shop at stores that emphasize big breasts, tiny waists, and full hips? Or stores that stock clothes in size XX-Small?

- Can I be a feminist and still read beauty magazines obsessively? And not just because I’m writing radical poems with them, but maybe because I sometimes (most times) care about the advice they give, even if I know it’s superficial and ridiculous!

- Can I be a feminist and watch shows where women do 90 percent of the housework, the cooking, the cleaning, and on and on? Can I still love shows that subscribe to super-sexist ideas about women?

- Can I be a feminist and have a crush on James—someone who didn’t even know about feminism before we met, someone who is dating someone else, someone who doesn’t fully know who I am, since, if he knew me, he’d know that what he’s giving is not enough.

- Can I be feminist and want to be pretty?

- Can I be feminist and sometimes want to be quiet and shy?

- Can I be feminist and still be friends with people who don’t care about women’s rights as much as I do?

- Can I be feminist sometimes, and take a break other times?

- Can I just be me?