Books

Was I In A Cult? How My Own Experience In A Doomsday Church Inspired My Novel

Who doesn’t love a good cult story, right? Charles Manson, Jim Jones, NXIVM. By the time these stories hit the news, it’s never for a good reason. Crimes have been committed. Strange belief systems are exposed. Sometimes people have even lost their lives. If you’re anything like me, you pour over these true crime tales and wonder: Why would anyone ever willingly join a cult?

Because cults are really good at hiding in plain sight.

As I entered junior high, most of my classmates were preoccupied with friends and grades and fitting in. I, however, was preoccupied with the end of the world. The first time I thought the world was ending, I was in the seventh grade riding the bus to school. It was a cold, icy morning. Our bus probably never should have been on the roads, but Minnesotans never back down from inclement weather. As our bus chugged up the hill, it slid into a shallow ditch. I gripped the straps of my backpack and told everyone, "This is it! The end of the world!"

I got more than a few strange looks that morning.

A bus skidding on some ice isn’t exactly an apocalyptic event. But my family had recently joined a church that was obsessed with the end of the world. My parents, who were lapsed Methodists, had been seeking spiritual nourishment. One day some men and women in modest suits and dresses rang our doorbell and invited us to come to their church. My parents were convinced it was a sign from God. Until then, my religious experiences had consisted of begrudgingly attending church a few times a year and dropping out of Sunday school.

The main message was always the same—the world was going to end any minute, and if you weren’t on God’s good side, you were going to die.

Suddenly we went to church every Sunday, which looked more like a retirement home than a church. It had no pews, no stained-glass windows, and no crosses. Just rows of pink padded chairs and bad hotel art. Services lasted for hours. We also went to a Bible study every Wednesday night. The main message was always the same: The world was going to end any minute, and if you weren’t on God’s good side, you were going to die. And not only would God destroy your physical body, He would also destroy the memory of you as well. It would be as though you never existed. Fun times, right?

This group had a lot of rules, and we were expected to follow them. Only men could be in positions of power or leadership. Only men could preach. Only men could lead a family. Women couldn’t wear too much makeup or flirt with men. Homosexuality was a sin. No blood transfusions. College was frowned upon. It took your time and focus away from God. Sports and other extracurricular activities were also discouraged. We weren’t supposed to associate with anyone outside the church. "Bad associations spoil useful habits," the group told us. It was All God, All the Time.

I have always been an anxious perfectionist, so I jumped into my new religion feet first. If I was going to do this God thing, I would do it all the way! I remember shopping with my mom for new church clothes. The group expected its members to wear conservative clothing. It was the '90s, and I was really into broom skirts, which were a better option than dresses. My mom even let me wear my black Converse sneakers with them sometimes. At first I felt powerful sitting through hours of services in those colorful, crinkly skirts, feeling sorry for all the poor unfortunate souls who weren’t in our group. And, if I’m being honest, I felt better than them. I was special. I knew the truth. I was part of an elite group. I gave sermons to my friends, trying to convince them why their religions were so dangerously bad.

"Sorry I haven’t written in so long," I wrote in my journal on November 27, 1993. "I’m in seventh grade! I’m a [redacted] now! We’ve been studying for five months. Did you know that if you learn and preach God’s word you get everlasting life on Earth?"

Doubting the group, we were told, meant Satan was whispering in our ears. And Satan, they told us, was lurking around every corner, waiting to pull us back to the dark side. One of our mentors told me she had proof that Satan was real. She dramatically relayed a story about a friend who was holding a Bible. He said, "If you exist, Satan, make this Bible fly across the room!" Not only did the Bible fly, she told me, it screamed.

My family gave up Christmas that first year in the group. Christmas, we were told, was a Pagan holiday and offensive to God. Instead, we had a "gift day" in December, and I got the game Dream Phone. Calling a bunch of fake boys to see which one liked me didn’t take the sting out of missing our traditional ham dinner and watching Rudolph on TV. When my classmates made holiday-themed crafts and sang about Santa, I excused myself and sat in the library. Birthdays were also not to be celebrated, and so my thirteenth birthday got skipped over. I was like a reserve Molly Ringwald in Sixteen Candles: My family openly ignored my birthday, and I had to pretend to be okay with it. (I wasn’t.) I had to turn down birthday party invitations, which was not exactly a great way to make friends in middle school.

Pretending someone didn’t exist right to their face? That seemed cruel. And this group preached that God was love.

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment I began to doubt this group and its messaging. But I do remember going to a dance at our mentors' farm. My family and I line danced in a hot, sweaty barn. Dancing with a member of the opposite sex was not allowed; neither was dating without a chaperone. My sister and I went outside with a couple of girls our age. We passed by a young man who was walking by himself, and I said hello. He smiled and said hello back. As soon as he was out of earshot, the girls yelled at me for speaking to him. "He’s been disfellowshipped," they said, their term for kicking members out of the church. "We’re not allowed to talk to him."

Pretending someone didn’t exist right to their face? That seemed cruel. And this group preached that God was love. I couldn’t reconcile that disconnect, and eventually my parents let me leave the group. They left a few years later, tired of the message that no one outside the group could be trusted.

Skip ahead about 25 years. I was looking for a literary agent to represent my young adult novel about a girl raised in a modern-day circus. Her father is the charismatic, controlling ringleader who isolates her from the outside world. In the fall of 2017, I had a phone chat with an agent interested in my book. We had a great discussion about the plot and characters. Toward the end of our chat, she said, "This is a cult book. You need to commit to the cult and flesh it out."

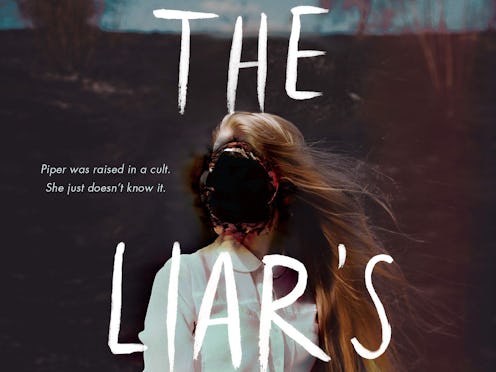

A cult book? When I started writing The Liar’s Daughter, I never intended for it to be about a cult. But I decided to mull over this agent’s advice. Around this same time, I started watching the A&E docuseries by Leah Remini called Scientology and the Aftermath. My jaw kind of hit the floor. So many of her experiences in Scientology mirrored my experiences. The fear of outsiders. Being shunned by family or friends if you choose to leave. In one episode, Leah even interviewed former members of the same religious group I had been in.

For most of my life, I’d downplayed the negative effects of my time in that group. Sure, I’ve struggled to trust organized religion ever since, and authority in general. I’m afraid to let my daughter attend church, which is a sore point in my marriage. And when my sister came out as gay years after we’d left the group, a part of me still feared God would destroy her simply for being her amazing self. But as I watched those former members lay out their pain for all to see, I had to ask myself: Had I been in a cult?

As I dove back into revising The Liar’s Daughter, I used all my confusion, anxiety, and anger from my days in that group. Like me, the main character of Piper is a "good girl" who does what she’s told. She’s been raised in a cult, only she doesn’t realize it’s a cult. After she’s rescued, she’s desperate to return. Her life in the Community is all she’s ever known. Piper is a fiercely loyal person, and that loyalty is exploited again and again throughout the novel.

Cults attract people from all races, ages, and education levels. They exploit the human need to belong and to be seen. But cults aren’t about belonging at all.

I also researched many other cults as I wrote my book, from Charles Manson’s The Family to Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple. One of the most unsettling cults I read about, also called The Family, was run by a beautiful Australian woman named Anne Hamilton-Byrne who "collected" children. The pattern that emerged as I read about all these different cults is that there is no “type” of person that is more likely to join a cult. Cults attract people from all races, ages, and education levels. They exploit the human need to belong and to be seen. But cults aren’t about belonging at all. They’re about fitting in. And children are the most vulnerable members of any cult. They have no say in what happens to them.

The final version of The Liar’s Daughter is not the story I set out to tell; it turns out, it was the story I needed to tell. For Piper, who is lost and afraid and unable to trust herself. For my younger self, trying to figure out who she was, what she stood for, and where she fit. And for anyone who has ever felt lost and needed to be found. This book is for us.

I still love a good cult story, though.