Entertainment

Netflix's New True Crime Series Is The Most Bizarre Thing You've Ever Watched

In the early 1980s, Henry Lee Lucas was arrested on charges of unlawful possession of a firearm. Once in custody, he confessed to a double murder. Then another murder and another. It took over two years for Lucas, one-eyed and slow-talking, to spill his confessions, describing how he became, murder by murder, the most prolific serial killer in history. His videotaped police interviews make up the bulk of The Confession Killers, a Netflix limited series chronicling his supposed crime binge. In compelling archival footage, investigators from around the country visit the small Texas jail where Lucas is held, fishing for confessions to unsolved homicides. For the reward of a strawberry milkshake, Lucas is happy to oblige. But when journalists eventually exposed discrepancies in his accounts, Lucas was revealed to be a fraud. Even now, 35 years later, doubt lingers over which of the 600 murders he claimed can be credibly attributed to a man once considered the most dangerous in America.

Henry Lee Lucas died in 2001 after suffering a heart attack while serving a prison sentence for the 1979 murder of “Orange Socks” — a Jane Doe who became known by the only item of clothes she was wearing when her body was found. He was 64 by then and had cheated death before. In 1988, his death by lethal injection sentence was commuted by Texas governor George W. Bush, citing questions about the conviction, including Lucas’s recanted confession to the Orange Socks murder and a lack of physical evidence. 152 people were executed during Bush’s tenure; Lucas was the only man he spared.

Perhaps ironically, the murder which Lucas most certainly committed dates back to decades before he embarked on the confession spree that made him famous. On January 11, 1960, Lucas, who had grown up in an abusive environment, murdered his mother after a dispute about whether he should return to the family home to care for her. He served 15 years in a Michigan prison for beating her to death.

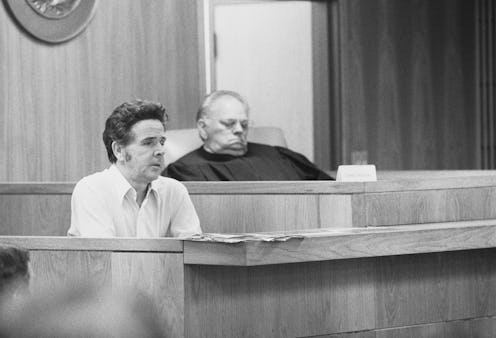

Then, in 1983, Lucas was picked up for illegally carrying a weapon. In custody, he confessed to killing two women, his young girlfriend and his elderly landlord. It was at his arraignment for those crimes that he asked the judge what they should do about the other 100 women he’d killed, setting in motion the charade that would see him claim responsibility, at times, for hundreds of murders. In exchange for preferential treatment—he was fed steaks and hamburgers and allowed to roam the jail without handcuffs—he would tell detectives what they needed to hear to clear cases that had long gone cold.

And it wasn’t until Dallas Times Herald reporter Hugh Aynesworth started drawing attention to discrepancies in the cases in 1985 that the avowals would stop. In one notable example, it was revealed that for all eight of Lucas’s murder admissions to be true for the month of October 1978, he would need to have driven 11,000 miles. Aynesworth would go on to be a Pulitzer finalist for his contribution.

Even Ken Anderson, a district attorney on the team that successfully prosecuted Lucas for the murder of Orange Socks, told the New York Times he believed Lucas committed only a handful of murders. But despite his eventual recantations, Lucas didn’t show much remorse for the fraud that cheated so many families out of real justice. For example, in 1999, Lucas grew interested in the so-called Railroad Killer, a drifter linked to eight murders. ''If this was 1983, I'd claim these murders, too,'' Lucas told The Houston Chronicle at the time.

Which all makes Netflix’s latest entry into the world of true crime, more of a police exposé and psychological drama than a whodunnit. In prison, Lucas found the popularity that alluded him in life. In exchange, law enforcement was allowed to claim easy if false victories. It's only more recently that the real work of solving these decades-old murders has started. Using DNA tools which didn’t exist when Henry Lee Lucas was still alive, the web of confessions he left behind is still in the process of being resolved.