Books

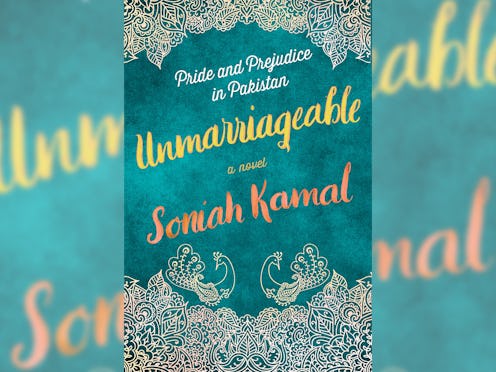

How Author Soniah Kamal Retold 'Pride & Prejudice' In Modern Day Pakistan

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single reader in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a Pride and Prejudice retelling. At least, that certainly seems to be the case. From Bridget Jones’s Diary to Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, there is practically no end to where writers will take Jane Austen’s classic novel next. It’s been retold in a multitude of genres: mystery, thriller, romance, YA; and through the vantage point of a variety of Austen’s characters: Mary Bennet, Mr. Darcy, the servants at Longbourn. Now, Janeites will have one more manifestation of P&P to add to their shelves — and this time, it’ll take you all the way to Pakistan.

Unmarriageable: Pride and Prejudice in Pakistan by Soniah Kamal, puts a modern feminist twist on Austen’s already-feminist work, transporting readers to an English Lit classroom in Pakistan, where instructor Alysba Binat teaches her all-female students not only to interrogate the themes throughout classic literature, but to interrogate the double standards that permeate their lives, as well. When readers meet Alys, she’s guiding her students through an exercise rewriting the first line of Pride and Prejudice.

“It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single woman in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a husband!”, Alys writes on the chalkboard, before asking her students how the gender-switch makes them feel. It’s a move designed to not only demonstrate the double standards women of Austen’s time were held to, but how social expectations weigh on the lives of modern young women. It’s an exercise that Kamal has demonstrated in her own English Literature classrooms.

“My variation is definitely Alys’s because, as I say in the novel, it really does highlight the irony and absurdity of Austen’s first sentence in Pride and Prejudice,” Kamal tells Bustle. “I had this idea while coming up with exercises for my classes. However, it’s also a fun game I indulge in with myself at weddings and other functions meant to facilitate happily-ever-afters.”

Alys — in true Elizabeth Bennet fashion — encourages all the women around her, from her students to her sisters to her best friend, to live lives of their choosing. Advocating for everything from education to masturbation, Alys preaches independence, financial freedom, and critical thinking. When she meets her own Mr. Darsee, at a days-long wedding celebration, they, of course, butt heads. But in Kamal’s reimagining, it’s over Alys’s choice of reading material, rather than her manners.

"However, it’s also a fun game I indulge in with myself at weddings and other functions meant to facilitate happily-ever-afters.”

Alys, like her predecessor, Elizabeth, is a prolific reader — often viewing the world through the lens of literature. At one of the VIP events the Binat family attends, Alys wonders aloud “how many Emma Bovarys are here.” She classifies her peers through the characters in many of the books she’s read. Kamal admits to seeing the world similarly as well.

“Just look around you — there’s always an Austen character, or a character from some book skulking around,” the author says, describing her recent return from a trip to Pakistan, where she observed characters as alive and varied as May Welland, Eustacia Vye, and Nandis and Zahras.

“My first exposure to viewing people like this was in Daphne du Maurier’s short story 'The Blue Lens,' in which the protagonist sees humans as animals based on certain traits — so someone is a naïve cow while another a cunning snake.”

“Just look around you — there’s always an Austen character, or a character from some book skulking around,

This: the universality, the relatability, the applicability of Austen’s characters, is just one reason why the author’s work not only endures, but is subject to frequent (and popular) reimaginings.

“Austen is a master psychologist and captures the human propensity for pretentiousness and other foibles like few others,” explains Kamal, adding that while the film adaptations popularized the romances in Austen’s writing, Austen herself glossed over the love stories and chose not to show weddings in her novels.

“Rather, she’s interested in exposing hypocrisies, class biases, and drawing room constraints,” Kamal says. “I’ve taken Austen’s concerns regarding friendship, sisterhood, and autonomy and explored them further in Unmarriageable. Charlotte Lucas may well have ruined her chances for happiness had she listened to Elizabeth Bennet’s hesitations regarding Mr. Collins. Instead, Austen gives Charlotte agency and the good sense to do what is best for her, rather than follow her friends. It’s a lesson we see being learned every day.”

Giving her readers something to enjoy was also at the forefront of Kamal’s mind. “In these troubled times, I really wanted to write something that would make readers’ smile and bring them joy and sunniness, which is what Pride and Prejudice does too,” she adds.

Another key to Austen’s enduring popularity isn’t just that her work resonates across different generations of readers, but across different cultures too — perhaps no reimagining demonstrates this as much as Kamal’s, which seamlessly translates the plot of Pride and Prejudice to the modern-day Muslim world. (Although Kamal’s characters are not all strictly Muslim.)

“Whether Pakistan, Japan, Norway, or any country, we see Austen’s characters reflected all too well in our family, friends, neighbors,” Kamal says. “Who doesn’t have a relative as nasty as Mrs. Norris? Or know a social climbing frenemy like Isabella Thorpe? Or a General Tilney like terror for a parent?”

“Whether Pakistan, Japan, Norway, or any country, we see Austen’s characters reflected all too well in our family, friends, neighbors."

The social pressures translate across time and culture, as well. “If you belong to a patriarchal and class-based culture, Austen’s work speaks to the ongoing requirement for girls and women to maintain good reputations in order to be respected, and for boys and men to make a lot of money, which is a gender trapping in itself,” says Kamal. “If a girl marries well because she’s beautiful and behaves, then a guy marries well because he has the potential to offer a great lifestyle. Even cultures where these rigid rules no longer apply can yet recognize them.”

Unlike a number of other reimaginings of Austen’s work, Kamal actually includes Jane Austen and the original Pride and Prejudice in Unmarriageable — Austen’s work is not only present in Alys’s classroom, but is frequently on her mind as well. “Jane Austen is a huge part of the British Literature Canon in a post-colonial country like Pakistan, and since Alys Binat is an English Literature teacher, it only made sense that she would teach Austen,” Kamal explains. “Also this was a way for me to bring up post-colonialism’s legacy, and language and class issues between English and Urdu.”

The author says these were fun parts of the novel for her to write. “At one point my Charlotte Lucas even points out to Alys Binat that Alys is Elizabeth Bennet. Of course, including these meta elements was a risk because you never know how readers are going to react but ultimately you just have to go with your gut. I also had a lovely time with the names, all of which have histories and origins in Urdu,” Kamal says.

Her names — Darsee for Mr. Darcy, which translates to tailor; Kaleen for Mr. Collins, refers to carpet, which is what his ancestors sold; Wickaam for George Wickham, has an extra ‘a’ to make the word “aam”, or “ordinary”; and Lady, a tribute to the fact that in her lifetime Austen did not publish under her name, but as ‘a Lady’ — are fun for readers to put together as well.

I ask Kamal what she imagines Austen might have thought about the many and varied manifestations of her work. “Jane Austen would have been thrilled and, I’m sure, very amused,” says Kamal. “In Austen’s own lifetime, it was frowned upon for women from good families to write for a living and I know Austen would have reveled in the fact that her work was making money because, like all independent minded women, she wanted to earn her own living. I don’t think Jane Austen would have been at all surprised that Pride and Prejudice is so beloved and adapted so frequently. After all, she called it her ‘light, bright and sparkling novel’ and knew fully the appeal of five unmarried sisters plus a marriage-worried mother.”

She also thinks the writer would have found interest in the myriad mediums her work has appeared in, since her lifetime. “Austen would definitely have had some choice observations to make about longevity and that while she had to self-publish her novels, they are now movies and TV serials and on the Internet and really every manifestation you can think of,” Kamal says.

"After all, she called it her ‘light, bright and sparkling novel’ and knew fully the appeal of five unmarried sisters plus a marriage-worried mother.”

Speaking to what Austen might have thought of modern readers’ relationships to her work is something Kamal is uniquely qualified to do — in addition to writing Unmarriageable, she’s an ambassador for the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation (JALF) — an organization founded by Jane Austen’s fifth great niece, Caroline Knight, to honor Austen’s relationship with libraries and learning.

“One of the biggest pleasures of JALF is meeting other JALF Ambassadors from so many different backgrounds, and knowing that we’ve all come together through love of Jane Austen and a desire to spread literacy," she says.