Books

True Crime Stories About Women Murderers Are Rare — But Necessary

Conventional wisdom is that the majority of true crime readers are women, an observation borne out of a 2010 study that found that women are bigger true crime fans than men. Anecdotally, at least, it seems women also make up the overwhelming majority of victims in true crime stories. Yet, one particular kind of woman is rare in these books: the female killer.

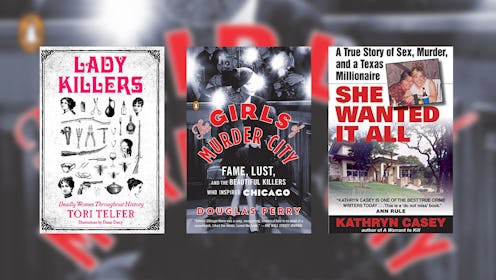

In 2017, Tori Telfer attempted to tell their stories in Lady Killers, which examined the lives and crimes of 14 women murderers. Telfer tells Bustle that the rarity of books about women who kill may be a result of what she called a "one-two punch of publicity and then amnesia," in which women murderers — especially serial ones — captivate the attention of both media makers and consumers, "but then after the fact, they don’t become icons like Jack the Ripper or Ted Bundy," they are instead forgotten. The public response to killer women, which includes whether and how they make it into true crime books, reflects gendered differences in broader assumptions about the characteristics and motivations of killers.

Women who kill are inevitably met with publicity initially, because they shatter many of our society’s foundational myths about the nature and role of women — that women are inherently kind, gentle, and nurturing.

Historian and journalist Douglas Perry extensively researched a series of killings by women in 1924 Chicago that generated volumes of sensational publicity for his book. In The Girls of Murder City, he chronicles the murderesses’ trials and the public reckoning they sparked. These trials were “huge public spectacles,” he tells Bustle, driven by the perceived need to explain the transgressive behavior of these women.

"Telfer tells Bustle that the rarity of books about women who kill may be a result of what she called a "one-two punch of publicity and then amnesia."

Perry says that press coverage of the trials reflected a widespread belief "that a woman wasn’t capable of murder. If a woman killed someone, there had to be extenuating circumstances. She was driven to it — driven crazy — by bad booze (this was during Prohibition) or a broken heart or even the constant clamor of city life." It is easy for true crime writers and journalists to fall back on reductive explanations — like that she is either “mad, bad, or a victim,” as Siobhan Weare, a UK-based researcher focusing on women and crime, succinctly suggests in her legal scholarship on female murderers — to tell a tidy story of the transgressive woman that conforms to rather than challenges normative beliefs about femininity.

Kathryn Casey, journalist and author of 11 true crime books, including She Wanted It All, about convicted murderer Celeste Beard, tells Bustle that this desire to explain away killer women persists today. Casey says that in her investigations of contemporary murders, she “noticed that friends and family of women killers sometimes… make excuses for them. They have a hard time admitting that a woman they know has committed such an evil act.” Casey, however, does not settle for convenient or reductive explanations, instead she seeks to uncover in murderesses the full spectrum of humanity, however hard to confront.

"They have a hard time admitting that a woman they know has committed such an evil act."

Eventually, as Telfer describes, the fascination with each new killer woman dies down and the fact that women do commit murder drifts from a present reality to a peculiar anomaly. Of course, this sets the stage perfectly for widespread shock and awe when the next killer woman comes along, creating a public that is, as Perry tells Bustle, “desperate to come up with an explanation for this supposedly new phenomenon of women committing murder.”

As an example of this spectacular feat of collective amnesia, in Lady Killers, Telfer recalls the American media’s labeling of late 20th-century killer Aileen Wuornos as the “First Female Serial Killer,” despite the many killer women who preceded Wuornos, several of whom are profiled in Telfer’s book.

“[Women serial killers are] not seen as a danger that might happen again,” Telfer tells Bustle. The tricky part, she noted, is that, statistically speaking, that is a sound assumption. According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, women commit five percent of murders worldwide. Data from Radford University indicates that 11.4 percent of serial killers worldwide since 1900 have been women; although women seem to make up a larger portion of serial killers than non-serial murderers, serial killings are far less common.

To write thoughtful, unbiased true crime narratives about women killers, Perry tells Bustle, “It’s important to recognize cultural and gender biases — to make sure you’re both addressing those biases and not falling victim to them.” Those biases might include depictions of a female killer’s motives that deny her agency by suggesting she was driven to kill by some external force such as the influence of a man, hormonal imbalance, or "hysteria," or stories that make her into a reductive trope such as the man-hater on a murderous rampage or the ugly or odd woman seeking revenge on the society that rejected her.

"It’s important to recognize cultural and gender biases — to make sure you’re both addressing those biases and not falling victim to them."

Attention to these considerations often manifests in very subtle ways. As feminist and writer Emma Copley Eisenberg wrote for The Paris Review in a story titled "How To Write A Feminist 'Dead Girl' Story," cultural bias lives “in the point of view, the characterizations, the hints as to the writer’s priorities that are made manifest in their every tiny choice.”

Dr. Anna Frost, in her Ph.D. dissertation on American consumption of true crime stories, argues that true crime stories function as a “restoration ritual” to help readers respond to and understand disruptive and often violent transgressions. From this perspective, true crime stories about killer women, however rare, reveal a lot about how the public receives and understands women who kill. “On the one hand, true crime books uphold conservative values — policemen are heroes, criminals are punished, sometimes by death,” Frost writes. But, on the other hand, if written with nuance and care, they can unflinchingly explore the complicated morass of human behavior and challenge our preconceptions about how the world works.

Narratives that rely on static interpretations of identity and ideas about "what makes a criminal" can be reassuring in that they suggest that people who commit crimes always appear in this same kind of way with the same kind of story. This is not only false, but also boring.

According to Tori Telfer, writing true crime stories about women who kill is a feminist project “in that all women’s history is inherently feminist… A world in which we pretend there aren’t female serial killers is sort of a weird Victorian ‘all women are flawless angels’ world and that’s certainly not a feminist stance.”

It’s not that simple, though. “I do get worried sometimes that people will read my book and be like, ‘GIRL POWER!’ and forget that many, many real people died between those pages. I don’t want people to forget that these women were real and almost all of them had higher body counts than Jack the Ripper,” Telfer tells Bustle.

True stories that show murderesses every bit as complex and human as the obsessively studied and unfortunately glamorized (usually white) male murderers are important, not to "redeem" female killers, but, as Telfer says, “to remember that women sometimes kill serially,” because that’s what humans sometimes do. If there’s no room in popular imagination “to see the full spectrum of how women can behave” this produces an understanding of women in general as less than fully human.