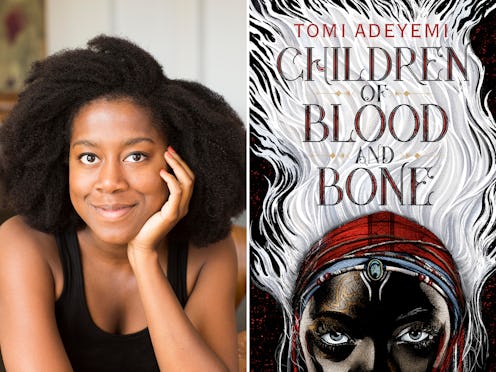

Books

This New YA Book Is A Fantasy — But It's About The Reality Of Growing Up Black

There are many reasons to write a book, and Tomi Adeyemi wrote Children of Blood and Bone because she had to. Because she was told that this story didn't matter. Not this story, specifically, but the story behind the story of her young adult fantasy novel: the story of how it feels to be a black person in America. And if you tell Adeyemi that she can't do something, you may as well just get out of her way.

"If you can tell me I can’t do something or if you try to hurt me, it’s like, 'f*ck you, I’m going to hurt you. But not like with my fists,'" she tells me over the phone. "Oh, you don’t want to see black people in a story? I’m going to make a story with all black people and guess what? It's going to be so good that you have to see it... That’s where it comes from. I’ll feel my pain, but I’m going to fight back. So, you can hurt me, but you’re not going to put me down. And I think that really is the story of the black experience."

Enter Children of Blood and Bone, which will be released by Macmillan Publishers on March 6. The novel follows Zélie Adebola, whose mother was hung from a tree outside of her house when she was six-years-old for being a dark-skinned, white-haired maji. Years later, Zélie lives in perpetual fear of a magic-hating king and a society constructed to keep her and those like her down, even long after magic is gone. So when she's given the opportunity to bring it back, to strike against the king who has massacred and oppressed her people, how can she not? And how far will she have to go to do it?

"I’ll feel my pain, but I’m going to fight back. So, you can hurt me, but you’re not going to put me down. And I think that really is the story of the black experience."

Of course, it's a roughly 500-page novel, so things are far more complicated than a simple battle between "good" and "evil." Adeyemi explores what it means to be an ally, the lies that oppressors tell themselves to avoid the truth of their own prejudice, and, above all, what it feels like to be afraid that every second of every day may be your last simply because of the way you look. It's the story of the black experience, as she says, and it was that experience — the rage, the pain, the fear — that pushed her to write this book.

"That’s the black story. You can take everything from me, and somewhere deep down I will find a way to come back, and I will come back stronger."

"The black story is a specific story. Your ancestors were taken from your homeland and taken to a completely new homeland, forced to labor, treated like cattle, systematically oppressed, and then, when you were freed from slavery, they found a new way to oppress you," she says. "[But] it’s the Maya Angelou poem, 'Still I Rise.' That’s the black story. You can take everything from me, and somewhere deep down I will find a way to come back and I will come back stronger. I will come for your box office with Black Panther, and I will come for your shelves with Children of Blood and Bone, and I will come for your laughs with Girls Trip, and I will come for your country with President Obama."

For her, writing this book, even through the misconception that books with all-POC casts won't sell, was her way of rising. "I think [my book] is just one example in the long history of black people finding a way to thrive when not only are so many cards stacked against them but so many people are actively like 'how can I throw more cards against you?'"

Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi, $11, Amazon

Because this story was so important, because it mattered so much to her, Adeyemi did everything she could to get it right — which included making ample use of numerous sensitivity (authenticity) readers. And, yes, she did so even though she is a Nigerian-American writing a West African-inspired fantasy world. "I’ve been black my whole life. I have 24 years of research on what it is like to be black — and there are things I got wrong," she says. "I am putting this in a fantasy world, so everything is a metaphor for something. There were some things that didn't work because, if we strip something away, then the metaphor becomes this thing that you’re not trying to say. And there [were] a sh*t ton of things that I was able to get better, because you’re sitting with that person and they’re like, 'Here are all the possible ramifications of this, and what happens in this scene, and how you describe this person in this scene.' When a person is holding a magnifying glass to every single part of your world, it’s so helpful."

According to her, the result is that every word, every line, every paragraph of her novel feels "intentional" — which reduces the pressure for her. "I felt the pressure for eight months when I put myself in the ringer. [Now] there’s not one thing in this book that someone could [point out] that I haven’t already thought of and have thought about deeply. The ramifications, the potential implications, the potential interpretations of something. Every single aspect of my book, every single word on the page, has been deeply analyzed, it’s all so intentional."

"I’ve been black my whole life. I have 24 years of research on what it is like to be black — and there are things I got wrong."

And there was a lot that Adeyemi wanted to examine with this novel. With the character of Princess Amari, whose father massacred the maji and whose escape from the palace with a magic scroll launches Zélie's adventure, Adeyemi wanted to explore what it means to be an ally. She wanted to explore how to use one's power and privilege to help those that have been oppressed either by yourself or by your ancestors — and how much allies and the oppressed can achieve when they work together. "Sometimes, as marginalized folks, we can be like 'no, get away from me, I want to do this all on my own.' That’s not how change works," she says. "Even if we are perfectly unified as a force, I’m not saying we can’t do a sh*t ton, but we need allies."

With Inan, the crown prince who attempts to stop Zélie from bringing magic back to Orisha, Adeyemi wanted to explore the idea of oppression as something that one has been taught but still chooses to uphold. Inan is a complicated character with a lot to deal with internally and externally throughout the novel, but, though his journey was particularly difficult for Adeyemi, it's one she nevertheless feels is an important one to show. "You’re not going to undo years and years of hatred and racism in a moment," she explains. "You don’t undo that in a week. You don’t undo that in a month. It takes several years to unlearn that. It’s a process."

"This doesn’t end at a new hashtag. It’s constant. You can’t go on Twitter without seeing something horrible that’s happening to your people."

Finally, the central character of Zélie is the one that Adeyemi admits is the most like her, and that's because she embodies the fear that drove Adeyemi to write the novel in the first place. In a world where the Black Lives Matter movement begs for society to acknowledge that the shooting of unarmed black men and women happens regularly, and the system cares so little for these lost lives that the officers who do the shooting are often exonerated, it can often feel that to be a black person is to be constantly afraid. And that's something that Adeyemi wrote this book to deal with.

"In 2017, every time I got in my car, it didn’t matter if I was just going to do groceries or run to CVS or even drive for two hours. Every time I got in my car, I was like I could die. I could be stopped by police, I could be killed, and that police officer would get off. That was my first thought every time I get behind the wheel of a car. And that is my life," she says. "[And there are] people who have already had these experiences. Who have seen their parents killed in front of them by police officers, who have been abused, who have had police officers come into their house and beat them up and break their spines... This doesn’t end at a new hashtag. It’s constant. You can’t go on Twitter without seeing something horrible that’s happening to your people. That’s what Zélie was about."

And, ultimately, that's what Children of Blood and Bone is about. The fear and the rage, the hate and the hope, the joy and the struggle, and everything in between — everything that Adeyemi has learned makes up the black experience. It is her story, it is our story, and you know what? It's so good that you have to see it.