Books

This New Book Imagines A World Where Toxic Masculinity Is An Actual Toxin

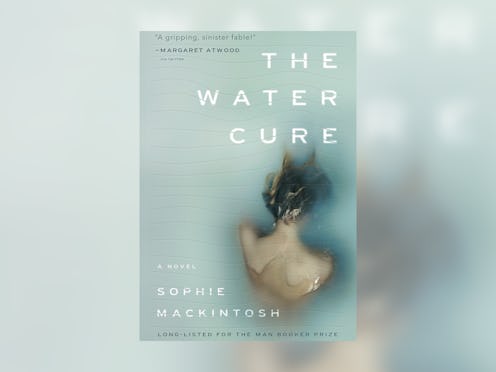

On a remote island off the coast of an unspecified continent, three sisters — Grace, Lia, and Sky — are hidden away from the world. It's a world where the water is poisoned, the air is polluted, and men are literally toxic. Their home, a large, crumbling mansion that once served as a rehabilitation center for abused women, is surrounded by shark-infested waters on one side and barbed wire on the other. Their father, called King, is the only man the sisters have ever seen; their mother administers unconventional therapies and performs cult-like rituals designed to strengthen the girls against the poisoned planet. Then, King disappears. This is where author Sophie Mackintosh’s debut novel, The Water Cure — longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize — begins.

The Water Cure imagines what the world would be like if toxic masculinity were actually toxic. “There is no hiding the damage the outside world can do, if a woman hasn’t been taking the right precautions to guard her body,” the sisters learn, their mother preaches. Side effects include: withering of the skin, wasting and hunching of the body, unexplained bleeding from anywhere, hair loss, agitation, hallucinations, total collapse, and more. What a woman wears into the world is critical. Without the right attire, a woman will shrink. Lungs burn. Eyes dry out. She disappears.

Already being compared to novels like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides, and Emma Cline’s The Girls, with definite echoes of Gillian Flynn’s Sharp Objects, The Water Cure is searing and ethereal, poetic and furious; it is filled with sibling rivalries, sexual tension, and mother/daughter envy. It rages against the dehumanization of women, patriarchal power, and environmental devastation, while still leaving readers enough space to question the role women play in upholding the patriarchy. Amid the violence is a deeply relatable coming-of-age story — one that sends each of the sisters spiraling off in different directions.

The Water Cure is told primarily through the perspective of Lia, the middle daughter, bookended by the perspectives of Grace, and then the three sisters collectively (Sky — the youngest sister and the only member of the family who was born on the island, therefore considered pure — is the only sister readers never hear from directly). Starting in the collective narrative, the novel begins at the moment when the sisters are first made aware their father is dead. King — the only one of the five permitted to travel to the mainland — disappears on a supply run; a blood-soaked boot washed ashore left behind as evidence.

In the wake of King’s disappearance, it becomes clear who is really in control of the island, the sisters, and their lives of violent isolation: Mother. Once King has gone, Mother keeps the girls in a medicated haze for a week, administering “blue insomnia tablets” and waking them only for brief meals of water and peanut butter crackers. Once the week is up, the girls awaken to a house filled scraps of paper that read “No more love!”. Love becomes a limited resource — affection, both given and received, is assigned and rationed. Lia is allocated none. Mother demands some from everyone.

Then, the men arrive. Llew, Gwil, and James — technically two men, brothers, and a boy, Llew’s son — simultaneously challenge and affirm everything the sisters have been taught to believe about themselves, their bodies, and the toxicity of the world. “There is a fluidity to his movements, despite his size, that tells me he has never had to justify his existence, has never had to fold himself into a hidden thing,” Lia thinks, of Llew. “I wonder what that must be like, to know that your body is irreproachable.”

They’re the first and only men the sisters have ever seen, aside from their father, and each sister responds differently, though all arrive at rage in their own time. The Water Cure is, after all, a feminist revenge fantasy at its core — one that recognizes the potent and freeing power of women’s anger. “The anger of the women seemed a force from outside them,” Mackintosh writes. “It was an anger that welled up deep in their chests. Without it, they would not have been able to survive. I personally have always welcomed it. The moments of power. The burning in my stomach. Be angry.”

For anyone discouraged by the myriad headlines of 2018, fatigued by the near-constant rage expected of and experienced by women, and looking for something to reawaken their angry feminist fighter in 2019, this January novel is one place to start. Who's to say toxic masculinity isn’t an actual toxin, anyway?