Books

This New Memoir Imagines What It Would Be Like To Be BFFs With Your Favorite Dead Author

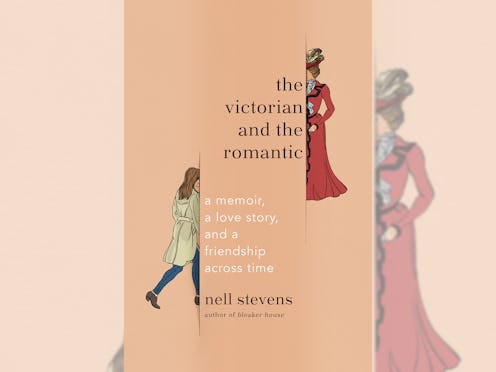

You’ll be able to recognize Nell Stevens’ writing for two qualities: one, her books are blend of memoir and fiction, memoir and research, memoir and history; and two, she’s a writer who’s great at writing about not writing. Stevens’ first genre-blending memoir, Bleaker House: Chasing My Novel to the End of the World, followed the aspiring novelist to the literal end of the world: Bleaker Island — a freezing, penguin-filled rock in the Falkland Islands, devoid of distractions like the internet and other people — where Stevens hoped to finish her novel. Instead, she returned with a memoir about not writing her novel. Her second book, The Victorian and the Romantic: A Memoir, a Love Story, and a Friendship Across Time, out now, follows Stevens as she struggles to finish her doctoral thesis while falling in love, having her heart broken, and communing with her favorite nineteenth century author, Elizabeth Gaskell, or as she fondly calls her, “Mrs. Gaskell."

But The Victorian and the Romantic also takes you into the (somewhat imagined) life and mind of Mrs. Gaskell herself — a braided narrative alternating between Stevens life as she muddles through love, heartbreak, and academia, and Gaskell’s life in the mid-1800s. As it turns out, the two have a lot in common: while Stevens’ doctoral thesis on Elizabeth Gaskell seems to be under constant critique, Gaskell’s biography of her recently deceased friend Charlotte Brontë has become the stuff of national scandal and potential lawsuits. “I have three people I want to libel,” Stevens quotes Gaskell as having written to her publisher, in the opening of The Victorian and the Romantic. (Stevens, in contrast, is careful to note she has no people she wants to libel.)

They’re both, in a sense, writing about their dead friends as well — Gaskell about her real-time friend, Brontë, and Stevens about her imagined friendship with Gaskell. In fact, much of the book is written as a letter to Gaskell, and the chapters in which Steven takes readers through the author's writing life and travels through Rome are written in the second person. "You owed it to your dead friend to tell the truth, but the truth was evasive and slippery and fought back tooth and nail from the page," Stevens writes to Gaskell.

They’re also both English women in love with American men they can’t have — Gaskell having met the Bostonian Charles Eliot Norton while traveling in Rome, and Stevens in love with her Boston-based grad school pal Max, who has taken up temporary residence in Paris. Both women will grapple with clobbering heartbreak before the memoir’s end and both, unsurprisingly, will find a way to muscle through it.

The Victorian and the Romantic by Nell Stevens, $20.81, Amazon

But the great love story of The Victorian and the Romantic isn’t that between Gaskell and Norton, Stevens and Max, but rather between Stevens and Gaskell themselves. If the original question of Stevens' doctoral thesis is, as she writes: "What does it mean to be homesick for an imaginary place?" — as Gaskell was for the America (and the American man) she never had the chance to visit — then the question of The Victorian and the Romantic is certainly: “What does it mean to be lovesick for an imaginary friend?” — or, at least, a friend one cannot meet in real life.

“I felt — still feel — a pang, something like lovesickness, when I think that Mrs. Gaskell and I can’t write each other,” Stevens writes, in The Victorian and the Romantic. “We would write such good letters, I think. We would have so much to say.”

And yet, before the memoir’s end, Stevens and Gaskell will meet — if only on the plain of expanded consciousness. In a morphine-induced hallucination, after emergency surgery to remove one of her ovaries, Stevens calls upon Mrs. Gaskell, who has, fantastically, appeared at her bedside, for advice in, of all things, sperm donation. Gaskell, to her credit, not only replies by assuring Stevens that no matter what choice she makes, she is the author of her experiences, rather than just the critic, but also by reminding Stevens that she best discharge herself from the hospital soon — her doctoral thesis is about to be late.