Books

This Is The Feminist Retelling Of Noah's Ark You Didn't Know You Needed

I didn't grow up in a religious home, but my childhood is filled with memories of my mother telling me and my sisters the story of the Great Flood. It is the perfect bedtime story — filled with adventure, drama, excitement, and the ultimate happy ending. I can recall countless nights spent snuggled in my parents big bed, listening to my mom excitedly describe Noah and the animals that rode on it, each one part of a perfect pair. In our living room, she even kept a wooden model of the ark and its passengers — the elephants and the alligators, the lions and the tigers, the cows and the pigs, were all there, but there was only one human figure: Noah.

I wondered about Noah's family: Who they were and why were they never included in the story? If all the animals had an other half, who was Noah's? Like the woman in the Book of Genesis, the character in my mother's story didn't even have an identity outside of "Noah's wife." But in Sarah Blake's Naamah, this mythical woman not only get a name, she gets a story and voice with which to tell it.

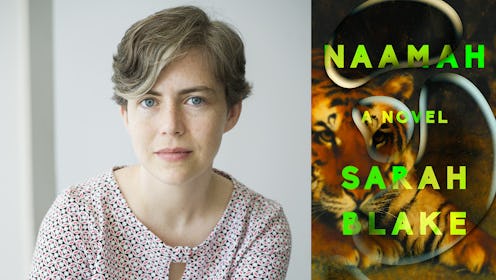

A fiercely feminist reimagining of the Great Flood, Naamah is the story of the biblical disaster that nearly ended life on earth, as seen through the eyes of the woman at its center. Instead of being a nameless, faceless character in someone else's story, Naamah finally gets her own narrative, and it is perhaps even more epic than her husband's.

In this retelling, Naamah becomes so much more than Noah's unnamed wife. She becomes a real woman, filled with wants, desires, and disappointments all her own. Finally, she is given a story of her own. Sarah Blake, the author responsible for writing it, tells Bustle what inspired her to write a novel about the great flood, what questions she was trying to answer with her story, and what classic story she'd like to reimagine next.

Bustle: What drew you to the story of Noah's Arc and inspired you to write a retelling of it?

Sarah Blake: I was drawn to the hopeless position of a woman stuck on an ark, uncertain of her future and the whole world's future along with it. How would she look out at that water and have hope? How would she look at her sons and tell them everything would be ok? I needed those answers in my own life, raising my son in times marked by radicalism and climate change.

"I wanted to find out who Naamah was — what type of woman could have survived that trial."

Was there something in particular you wanted to change or correct about the original? Was there a specific question you were trying to answer?

SB: In the original, Naamah isn't even named. She's referred to five times over the whole story and always when referring to all of the family on the ark, the group of them. I wanted to find out who Naamah was — what type of woman could have survived that trial, fed those animals, cleaned up after them, held her family together, seen them all through the flooding of the world.

What do you think retellings and reimaginings of classic stories have to offer readers who know and love the originals? What can we learn by reading new versions of old stories?

SB: The interesting thing about Noah's ark is we are already in love with the retellings of that story, more so than the original. There are countless children's books and playsets and famous paintings that we call to mind before thinking of the words of Genesis. The majority of those retellings don't include Naamah at all — just Noah and the animals, two by two. My book is a recentering of the story, and an imagining that fills many of the holes left by the retellings that came before it.

I think we're drawn to retellings to fill in those gaps, to expand the story, and to discover what's new while reliving what's familiar.

What is one story, fable, or novel you’d love to do a retelling of? Why?

SB: I've always loved the story of "The Twelve Dancing Princesses" — the women escaping the world, the men they've found asking nothing of them but their joy, the men they've left behind, meant to catch them, drugged and then killed. I've always wanted to spend more time in the world beneath their beds, with its sparkling trees and extravagant balls and enchantments that held fast.

Why do you think readers are drawn to retellings? Is it for comfort, predictability, a chance to see change?

SB: Every story leaves more stories untold. To give our attention to one person's story, we inevitably ignore someone else's. I think we're drawn to retellings to fill in those gaps, to expand the story, and to discover what's new while reliving what's familiar. Naamah does this: reveals everything that's happening for Naamah on the ark — her emotional life laid bare — while recreating the magic of the ark itself, the magic we already know, have known, of the rooms and rooms of animals.

This article was originally published on