Life

The Secret Feminist History Of The Titanic

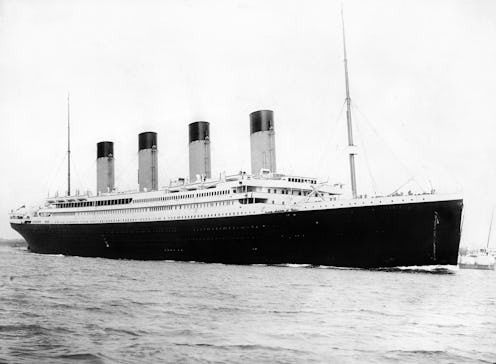

This year marks the 105th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic, the legendary "unsinkable" liner that would, of course, run into an iceberg on its maiden voyage, sink rapidly, and become a metaphor for man's hubris. There's a reason it became such a pop culture phenomenon, even before James Cameron got involved: its story seems tailor-made for moral gestures, grand tales of heroism and derring-do, and sweeping tragedies. (And that's without any Heart Of The Ocean nonsense.) However, one aspect of the tragedy doesn't get as much attention as it perhaps should: its particular and enduring affect on the emerging suffrage movement and first-wave feminism in Europe and the US.

The disaster's occurrence in 1912 hit smack-bang at the high point of suffrage and anti-suffrage movements on both sides of the Atlantic (and, because it was traveling from the UK to the US, it got both populations involved). Women's suffrage would be granted in the UK in 1918 and in the US by the 19th Amendment in 1920 — but the years beforehand were filled with battles in the press and in the real world between protestors for and against the concept, and the idea of women's equality more generally. And the Titanic, the most gigantic news story until the Second World War, would enter the debate in some very intriguing ways.

Famous Feminists Were On Board — And Only Some Survived

The most obvious part of the feminist legacy of the Titanic, and the one more widely known by casual historians, is that several of the passengers were actually suffrage activists — and would, before and afterwards, have direct influence on the history of the women's equality movement. The most famous is the "unsinkable" Molly Brown, immortalized both in the Titanic film and in one of her own; Brown ran for office in the US Senate years before the voyage and would use her fame afterwards to discuss women's rights on an international platform.

However, several other important feminist figures were also aboard. Journalist Helen Churchill Candee, who had authored the working woman's rallying cry How Women May Earn A Living in 1900, was in the same lifeboat as Brown and would man the oars with her. (She was also an explorer and a nurse who would treat Ernest Hemingway in World War I, so her survival made the world a more interesting place.) The British suffragette and assistant to Emmeline Pankhurst Elsie Bowerman also survived, and would go on to be the first English woman admitted to the bar.

However, the death of the journalist W.T. Stead, one of the most prominent British journalists of the time and a loud, eloquent supporter of the suffrage movement, dealt a major blow to the movement. Stead was apparently one of the many men who put women and children on lifeboats rather than entering one himself — and that sort of behavior, and what it meant for women's equality in general, would frame a fierce debate in the press that would have lasting marks on feminism.

The Sinking Of The Titanic Led To A Massive Debate About Feminism & Chivalry

The "women and children first" doctrine that operated during the Titanic's sinking, which resulted in a higher proportion of women than men being saved (though only in the upper classes; 51 percent of women below decks died, as opposed to 3 percent of first class ones), ignited one of the biggest debates in the history of feminism, even though nowadays it's been largely forgotten. Both suffragists and those opposed to female equality seized on the disaster to prove their points, and things rapidly got very ugly.

In 1912, The New York Times reported an argument between one of their reporters and suffragists, in which the suffragists apparently said that women were more valuable to the human race and should have been saved first, making the sacrifice of the men on board necessary rather than utterly heroic or chivalric. That, of course, opened a gigantic can of worms. The noted anarchist Emma Goldman would go on to publish an editorial calling the behavior of women on board the ship "pathetic" because of cultural norms declaring them weak, baby-like and in need of saving.

Anti-suffragists took on the entire incident as proof that women were naturally weaker and required men to take care of them in times of danger; men sacrificing themselves in such situations, one anti-suffrage publication said, was an act of "bravery, self-denial and unequalled consideration," and more than proved that men needed to take care of women in the political sphere, too. An advice columnist added that it proved that "man is eternally the protector of women" and that woman "obeys man instinctively." Why give women the vote when they couldn't take care of themselves? For anti-suffragists, the situation on the Titanic was proof that gender roles were innate, that women couldn't be relied upon to make hard sacrifices, and that women were actually better off being protected — and that feminists who accepted such chivalry were wanting to have their cake and eat it, too.

Another side of the debate was equally chaotic and loud. Some pointed out that the women who were saved were overwhelmingly privileged and white, and so weren't actually the "stronghold" of suffrage thinking in the first place. Others explored the rule of "women and children first" a bit more thoroughly. It had been established when the HMS Birkenhead ran aground in 1852, and female survivors from that disaster had explained that being given preference didn't make them feel any more special or higher-status. “It is hard to describe the sensation of oppression which is removed from one’s mind on knowing the utterly helpless part of the ship’s living cargo had been deposited in comparative safety,” one woman said. And they combated the "vulnerability" argument by saying, sharply, that while men may have saved women, women would have made sure there were enough lifeboats in the first place.

Whether or not women were "more valuable" became an angry point of dispute, but suffragists noted that, whether or not the women were saved, they were still powerless. They had "no voice in making and enforcing the laws on land or sea," one suffragist wrote, and that powerlessness was one of the big factors behind the death rates. "An equal chance of life," wrote the suffragette Lady Laura Aberconway to the Daily Mail in 1912, "is all that women in danger should ask or take from men." Others would celebrate the women who gave up their privilege to stay on the ship; Charlotte Perkins Gilman, the feminist activist and author of The Yellow Wallpaper, wrote that "We honor the women who waive this sex advantage and choose to die like brave and conscientious human beings."

So who won? Popular opinion was clearly swinging in the way of the suffragists, who would gain the right to vote in the next few years; but it would be a loud and exhausting fight for both sides. The Titanic and its feminist aftermath may well have influenced the shape of the debate in the future — an unexpected, and often forgotten, consequence of tragedy.