Entertainment

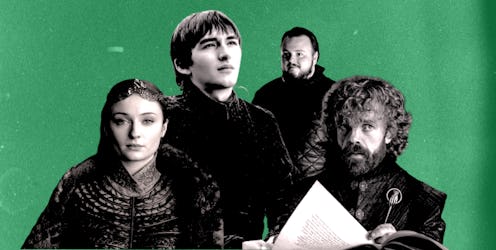

Why It Makes Perfect Sense That Bran, Sansa & Sam Came Out On Top On 'GoT'

For eight seasons, Game of Thrones convinced its viewers to believe in myths and dragons, in heroes who returned from the dead, and in prophecies and folktales. But after more than a few epic battles and displays of magic, it was a surprise that the series' closing half hour was spent on the sobering details of forming a council and ruling the Realm. For a show so focused on traditional heroism, the Game of Thrones series finale offered a humbling lesson on the kinds of heroes who actually matter.

After some heavy-handed buildup, the show expectedly positioned Daenerys Targaryen as a dictator-to-be, convinced of her righteousness. Daenerys won the Iron Throne after burning King’s Landing, achieving the dream she had always wanted, but yet the conqueror in her was still breathing fire. She had finally become the colonizer the show had pitched her as from the beginning. In the opening moments of the finale, it's up to Tyrion to commit the first act of rebellion, as he throws away the brooch that marked him as the Hand of the Queen.

It's a symbolic gesture that fits his personality. It's easy to understand why it is Tyrion, and not someone like Jon, who is first to rebel against their queen. In all of Game of Thrones, Tyrion is the one character we trust to be a thinker, an intellectual who understands the moment that powerful rulers become intoxicated by their own superhuman ability. By eschewing his responsibility to Daenerys, Tyrion Lannister also effectively rejects the definition of heroes Game of Thrones has been occupied with since Season 1. Instead, we realize the real heroes are the ones who commandeer change (Tyrion), who speak truth to power (Varys, Sansa), and who rise to governance when the world needs them instead of chasing leadership (Bran).

Game of Thrones knows that the true ruler is not one who swings swords, but one who has the intellectual appetite for ruling.

Game of Thrones is a show that has always studied the way its characters responded to power. Robert Baratheon was incapacitated by it, Joffrey Baratheon used it as an excuse to be even more shockingly cruel, Tommen Baratheon was debilitated by its corruptive needs, and Cersei Lannister was drunk on it for revenge. And it’s not just the rulers who actually sat on the Iron Throne who proved themselves terrible at ruling. Those who coveted the throne and fought for it from the sidelines were just as easily manipulated by its power. Daenerys, who believed she had a birthright to the throne, went from a young ingenue to an autocratic dictator. Stannis Baratheon allowed his lust for the throne to fan his irrational beliefs, leading him to sacrifice his own daughter in the process.

Like the ring in J. R. R. Tolkien’s magnum opus, the Iron Throne in Game of Thrones became the ultimate test of who was fit to sit on it. As its strongest contender, Daenerys was the hero who brought dragons back to a world that had ceased to believe in them, who amassed whole armies from nothing, who inspired loyalty. As her counterpart, Jon Snow was the hero who fought for the good of the people, whose first allegiance was to duty, who would be the last man standing in a battle. As the two representatives of Ice and Fire, the show had convinced us that the story rested on the shoulders of champions. This heroism is also depicted in the show’s cinematography. Shots of grandeur are often reserved for Jon, Dany, and sometimes even Arya, as their time fighting enemies and flying on dragons is inherently cinematic. Even in prophecies, the Hero for the dark ages was someone whose gallant description signaled him or her to be a great warrior.

But in the series’ final half hour, the heroes are not the gallant sword swingers or the enthusiastic foot soldiers in the great war. Instead we have Tyrion Lannister, the show’s most cerebral character who spent eight seasons scheming to keep himself alive, ruling alongside characters whose knowledge has been practical and arguably under-appreciated. There's Sansa Stark, who grew into the show’s most astute mind, who has fought to protect and nurture the North and understands that ruling is not merely occupying a seat of power but a responsibility toward your subjects. In the last two seasons, Sansa has been the only character to worry about the grain that will feed the armies and northmen; the only ruler angling for safety rather than destruction. There's Samwell Tarly, who spent his years dedicated to study and academia; who chose to document the story of Westeros and is now given respect for doing so.

And finally, there's Bran. With the Three-Eyed Raven becoming King of the Six Kingdoms, Game of Thrones may have delivered its most befitting lesson on the nature of a ruler. Bran Stark, who was flung from a tower in the show’s first episode and was crippled by the fall, as Three-Eyed Raven is trained in the magic of greensight. It gives him the ability to see into the past and learn from the mistakes of men, to see into the present and correct the wrongdoings, and to see into the future and enable a healthy version of it. After destruction by famine, by dragon fire, and by the long night, Game of Thrones knows that the true ruler is not one who swings swords, but one who has the intellectual appetite for ruling. And there is no one with the foresight of Bran Stark.

Which is perhaps why the closing moments show the new council engaging in important matters that concern the Realm. That the show does not end with an act of ultimate heroism but with the banalities of ruling affirms that governance does not require brawn, but brain. As Brienne of Tarth spends the final moments documenting for the history books, the show may have delivered the greatest lip service to its creator. When it comes to ruling, even the warrior must take to the pen.

This article was originally published on