It's not even a full two months into 2019, and the publishing industry is off to a record start on the outrage front. I've got a list of all the 2019 scandals in books so far, so strap in for an emotional roller-coaster ride. To paraphrase Liz Lemon, "Man, what a year, huh?"

Right now, it looks like publishing's year for 2019 might outpace 2018 in terms of sheer scandal volume. Last year, a sexual assault scandal postponed the Nobel Prize for Literature, perhaps indefinitely. Additionally, many prominent male writers were accused of sexual harassment and assault, including Daniel Handler, Junot Díaz, and Sherman Alexie. Further uproar ensued later in the year, when Díaz re-assumed his position as Chairman of the Pulitzer Prize Board, proving that men's lives are hardly ever ruined by accusations of bad behavior toward women.

So far, Bustle has counted five major scandals that have rocked publishing in 2019, by the time of this writing. Conversations surrounding most of these stories are still ongoing, for better or worse. That isn't necessarily a bad thing. Scandals are often indicative of larger problems within an industry, and drawing attention to those problems is a necessary step toward rectifying them.

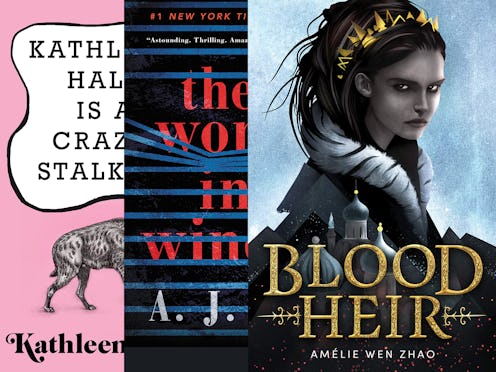

Kathleen Hale's Book of Essays

In October 2014, YA author Kathleen Hale published an essay in The Guardian, in which she recalled her self-described "light stalking" of a book blogger who posted a bad review of her debut novel to Goodreads. The episode culminated in Hale — who had obtained the blogger's address from a mutual contact — making an unannounced visit to the other woman's home.

Just over four years later, Hale has a deal for a book of essays, titled Kathleen Hale Is a Crazy Stalker, which is due out in 2019. The book takes its title from a line in Hale's Guardian essay, and publisher's copy leverages her past actions as a selling point, reading: "Kathleen Hale has been known to stalk people from time to time. Not recently, of course, and only online. Well, mostly online."

In an interview with Bustle about media portrayals of stalking, Julia R. Lippman, Ph.D, who wrote her dissertation on the intersection of media portrayals and public perceptions of stalking, said: "Positive media portrayals of stalking — like those where the pursuer is rewarded by 'getting the girl' — can lead people to see stalking in a more positive light." She added that this could lead to an increase in "stalking-type behaviors" and "decreased likelihood of victims seeing the behavior as a problem and therefore seeking help."

Marie Kondo's Netflix Series

Marie Kondo's 2014 book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, inspired Americans to throw out their junk and organize their homes. How Kondo's philosophy relates to books, however, has generated more than its fair share of controversy. Kondo suggests that you should narrow down your collection to include only the books that you cherish, rather than holding onto a large volume of titles for the hell of it. (She herself keeps about 30 books.)

As Bustle's Kerri Jarema wrote, much of the critique had racist and classist undertones, and the people who have room for a lot of books are those who can afford larger homes and apartments, and those who do not may feel relieved by Kondo's suggestions for thinning out their home libraries in a thoughtful and caring way.

The criticism of Kondo isn't about book nerds who want to keep their dozens, or even hundreds, of books, without criticism. It's about classist and racist rhetoric being used to take down a woman of color.

Amélie Wen Zhao's Debut Novel

French-Chinese-American author Amélie Wen Zhao's YA debut, Blood Heir, generated a fair amount of controversy on Twitter in January. Book bloggers who received advance copies of the novel took to the social media website to criticize book's treatment of its enslaved magic-users — believed to be people of color — one of whom sacrificed herself to save the life of the novel's white protagonist.

Zhao issued a public apology and voluntarily pulled Blood Heir from publication. Some incendiary writers seized upon the story, vilifying Zhao's critics as a "Twitter mob" who wanted to tear down a young creative and prevent her from joining the published fold. In response, people began to attack Blood Heir detractors, to the point of issuing death threats to the women of color who called out Zhao's problematic writing.

YA Twitter has organized an effort to get books by Ellen Oh and L.L. McKinney — two women of color who spoke out about Blood Heir and were later dogpiled by hateful trolls — into schools. You can learn more about it here.

Dan Mallory's Profile in 'The New Yorker'

The Feb. 11 issue of The New Yorker features a lengthy, investigative piece on Dan Mallory, the former executive editor of HarperCollins imprint William Morrow, who published his thriller novel The Woman in the Window under the pseudonym of A.J. Finn. According to the story, Mallory lied to employers and co-workers on multiple occasions, spinning stories about his — very much alive — mother's death from "Stage V" cancer, his Oxford doctorate, and his own supposed bouts of brain cancer. The lies do not end there, and you should read The New Yorker story for all the details.

The biggest issue with these revelations about Mallory, of course, is that they show how he, as a white man, rose to a position of power within the publishing industry, if not because of his lies — which went largely unchallenged — then at the very least unimpeded by them. Meanwhile, women of color must contend with lower salaries and higher hurdles to achieve much less than what Mallory was, for all intents and purposes, handed freely.

Mallory has since admitted that he lied about having cancer, issuing a statement through his public-relations representatives, which read, in part: "[O]n numerous occasions in the past, I have stated, implied, or allowed others to believe that I was afflicted with a physical malady instead of a psychological one: cancer, specifically." Instead of brain cancer, Mallory now says his deceptions were caused by "severe bipolar II disorder." Reporting on the scandal, The L.A. Times quoted UCLA psychiatry professor Carrie Bearden, who said that bipolar II disorder does not cause those who live with it to lie.

In spite of this, Mallory's second novel appears to be still be on track to be published in 2020.

Jill Abramson's Alleged Plagiarism

On Feb. 6, Vice News' Michael C Moynihan took to Twitter to discuss former New York Times editor Jill Abramson's latest book, Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts. Moynihan criticized the book's depictions of Vice, contained over three chapters that he claims "were clotted with mistakes. Lots of them." Those chapters also allegedly contained material plagiarized from Time Out, The New Yorker, and the Columbia Journalism Review. Another writer, Magic Is Dead author Ian Frisch, said that "Abramson plagiarized [him] at least seven times in her new book."

Moynihan and Frisch's assertions about Merchants of Truth were not the first sign of a problem with Abramson's new book. Uncorrected galley copies contained numerous inaccuracies, such as the location of Charlottesville, Virginia and the gender identity of writer Arielle Duhaime-Ross. Duhaime-Ross tweeted about the book, saying: "I met [Abramson] in June ‘17 in the VICE office. We chatted for less than 40 minutes. She took handwritten notes. I have not heard from her since, by which I mean she did not contact me for a fact-check."

An interview with Abramson, published Feb. 5 on The Cut, lent credibility to Duhaime-Ross' claim about the other writer's interview strategies. In the interview, Abramson insists: "I do not record. I’ve never recorded. I’m a very fast note-taker. When someone kind of says the 'it' thing that I have really wanted, I don’t start scribbling right away. I have an almost photographic memory and so I wait a beat or two while they’re onto something else, and then I write down the previous thing they said."

In a statement to The Washington Post, Abramson said that errors in Merchants of Truth's "70 pages of footnotes" led to the "claims of plagiarism," and that those errors would be corrected. "The notes don’t match up with the right pages in a few cases and this was unintentional and will be promptly corrected," Abramson told The Post. "The language is too close in some cases and should have been cited as quotations in the text. This, too, will be fixed."

According to The Washington Post, Abramson's work has drawn attention previously for its similarity to that of other writers. The Post cited the case of a 2018 article that contained an unattributed quote from a 2016 Think Progress piece by Ian Millhiser.

Well, there you have it, folks — all the scandals that have rocked the world of U.S. publishing in 2019 so far. Although these controversies have left a bad taste in many mouths, they have also broadened conversations on diversity in publishing, mental health, fact-checking, and more. Hopefully, those conversations can lead to meaningful change.