Life

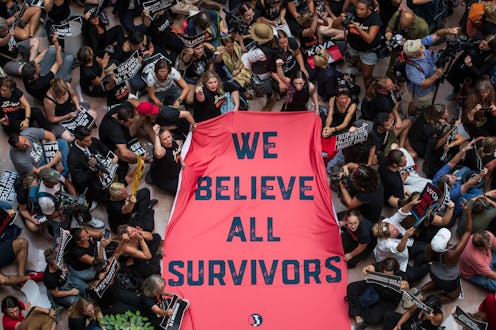

The Kavanaugh Hearings Exposed This Dangerous Rape Culture Myth. Why Do We Still Believe It?

If you've been white-knuckling it through coverage of Brett Kavanaugh's Supreme Court confirmation this week, you've probably noticed a rape culture myth that's been given a lot of air time: that a person who is good to some people cannot be a sexual abuser to others. This belief, present in everything from the September letter signed by 65 of Kavanaugh's former female classmates declaring that he "has always treated women with decency and respect,” to President Trump's declaration that Kavanaugh is innocent of the accusations against him because he is a "good man," highlights an underlying rape culture myth that's existed for years: how can someone "good" have possibly committed sexual assault?

This idea — that someone is committing 570 sexual assaults each day in this country, but not anyone that I know — has remained surprisingly tenacious, even after the resurgence of #MeToo activism has shown that sexually predatory behavior is present across all communities and social strata. In the week since the Kavanaugh hearings, I had numerous conversations, both online and off, with people who struggled with the idea.

While they believed the statistics — such as that one out of six women and one in 33 men will experience attempted or completed rape in their lifetimes, and that less than 40 percent of sexual assaults are reported to law enforcement — they had a harder time buying that any one of us might know someone who has committed assault. Some people I spoke to took the idea to mean that I was calling their specific community "bad" or immoral; others suggested that perhaps communities where many abusers had been revealed were abnormally full of "bad" people. Several told me that no one they knew had perpetrated sexual violence.

I struggled to make sense of these conversations. According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), 321,500 people survive sexual assault each year, with 70 percent of those assaults committed by someone the survivor knows — which would mean that if people know a survivor, it is also likely that they know the attacker. So why is believing this so difficult for so many people? I went to several sexual violence and gender studies experts to find answers.

Because It's Upsetting

Lisae C. Jordan, Esq., executive director and counsel of Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault, tells Bustle that many people refuse to believe that abusers live in their communities for an extremely simple reason: because "it's deeply disturbing to think that you were living your life amongst sex offenders."

Brian Pacheco, director of communications and media relations at Safe Horizon, a New York-based victim services non-profit organization, agrees. "I think it's always so difficult for families and individuals to think that their brother, their uncle, their father, their grandfather, their grandmother, that anybody who they trust can violate them in this way. But unfortunately, we know that that it's extremely possible," Pacheco tells Bustle. "We've heard [at Safe Horizons] from a lot of people [saying things] like, 'I didn't think my brother could do that. I didn't think my boyfriend was capable of that, he wasn't like that with me.'" But that emotional upset isn't the same as factual evidence. A person's kind or positive public actions, Pacheco warns, are "not a barometer for their behavior. Someone can absolutely be ... nice in public and then, commit atrocities in private."

Because It Makes Us Feel Safe

Despite statistics about how often sexual assault is committed by someone known to the survivor, the myth of "stranger danger" — that the greatest risk to our safety is posed by strangers who would attack us, often in a park or other public place — continues to be prevalent in the public perception of sexual assault.

"I think the 'stranger danger' myth makes people feel safer," Elizabeth L. Jeglic, a clinical psychologist, sexual violence prevention researcher, and professor at John Jay College, tells Bustle. "If a sex offender can really be anyone, then it makes the world a more dangerous place."

Pacheco has observed that some people may draw a feeling of safety from believing they're "smart" enough to avoid sexual predators. "They think that, 'That would never happen to me,' or 'I would never associate with those kinds of people.' But unfortunately, what we know is that with abusers, one of their tactics is manipulation ... They know how to [appear to be] a kind, sensitive, caring person. We call those 'grooming tactics' ...[abuse] never starts with somebody showing their abusive behavior. It always starts with gifts or ... with really nice behavior. It starts with compliments, it starts with, 'Let's hang out,' and it escalates over time. And that's a very intentional tactic on the abuser side."

"People want to believe that they are good decision-makers, and that if they make careful, deliberate choices about who their friends are, where they live, and who they associate with, then they will somehow be protected from being around a sexual assault perpetrator," Jhumka Gupta, a public health researcher and faculty at George Mason University's Department of Global and Community Health, tells Bustle.

Gupta notes that the flip side to this belief is often a set up for victim-blaming and shaming. "The corollary to this is the false perception that those who are friends with, live with, or otherwise interact in communities with sexual violence perpetrators must not have made good, responsible choices. It then becomes easier to make attributions to character flaws."

Because It Makes Us Feel Attacked

Some people might feel that saying their community is home to abusers is an attempt to smear their group, to present them as immoral or evil people. And that concern is understandable; throughout history, many marginalized groups have been falsely accused of being sexual predators, as part of targeted campaigns of discrimination and violence.

Think of the the myth that gay men are sexual abusers of young men, the Jim Crow-era myth that sexual assault is a crime primarily perpetrated by black men against white women, the myth that trans people are likely to commit assaults in public restrooms — or, as Gupta points out, current-day myths that stereotype most sexual predators as black and/or of lower socio-economic classes. Each of these myths is used to paint these populations as undeserving of basic human rights, and as justification for laws limiting what spaces trans people are allowed to physically enter, or the horrific lynching murders of black men.

That this might make some people nervous that their community is being maligned in a similar way is understandable, but it's not an excuse to avoid reckoning with the abusers present in every community.

"It is important for people to understand that when someone says, sex offenders are everywhere, it's not an attack on a specific community," says Jordan. She notes that one can show sensitivity around this issue by making clear that even if you're addressing particular allegations within one community, you're not only speaking about that group; rather, you're acknowledging "that there is a sex offender in every community and we all have to take responsibility for that, and change that."

Because It Might Force Us To Ask Ourselves Hard Questions

Gary Barker, president and CEO of Promundo-US, an international organization that works to promote gender justice and prevent violence through educational efforts aimed at men and boys, tells Bustle that there are a number of reasons people might be resistant to considering whether anyone close to them could be an abuser. But a big one might that be that it forces us to examine our past behavior, and think about whether we've done anything that might be abusive or coercive.

Jordan, of the Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault, agrees, noting, "I've had many conversations with men since the #MeToo movement — and especially since the brave testimony of Dr. Ford — who have said, I worry about what I did when I was a kid, and whether I ever went too far or whether I said something I shouldn't have."

But while this kind of self-examination can be scary, it's also the only way people will ever be able to shift our understanding about what kinds of behaviors are harmful. "I think that sort of self reflection is necessary to change our culture and important for everyone to think about," Jordan says.

Admitting that predators live in your community can also lead to another kind of uncomfortable self-examination: your role in rape culture, even if you've never abused a single person.

"Fear of taking a stand, and potential social consequences, can also cause people to be in denial about the pervasiveness of sexual assault perpetration in their social circles," says Gupta. "If people who otherwise claim to care about rape [prevention] acknowledge that they have close friends or relatives who perpetuate harmful myths about sexual violence, then they are faced with having to make decisions to disrupt such harmful attitudes and behaviors. Do they allow these behaviors (including crude jokes about women and rape, for instance) to continue unchecked? Or, do they actually say something and risk losing a friendship?"

What Can You Say To People Who Are In Denial?

Jordan says that the most important tack to take while having these conversations is also the simplest. "We need to remind people ... that most sex offenses are committed by someone known to the survivor. And we need to believe survivors. It's scary to think that that means that we know perpetrators and we haven't recognized some, and that we're at risk ourselves, but ultimately that's what we have to do."

Pacheco of Safe Horizon says that complex emotions are a normal response to seeing someone you know accused of assault. "If there’s an allegation in someone’s family or social circle, it’s OK to feel betrayed, it’s OK to feel angry, it’s OK to feel conflicted and upset and nervous." But we can remind people that feeling these emotions isn't the same as knowing facts. "Be cautious about saying, 'It didn’t happen because I know that [they are] a good person.' Because that’s not 100 percent foolproof.”

Thinking about whether there are sexual predators in your community isn't an easy pill to swallow. It's depressing to think that your friends, coworkers, or loved ones, people who have done nothing but support you, might also do unforgivable things to others. But talking about the prevalence of sexual violence isn't just the right thing to do so that survivors can be heard; it also can create a positive impact as we fight rape culture in our communities.

"We have to recognize that sexual violence is not an unusual, rare, super mysterious thing," stresses Jordan. "It's something that huge parts of the population have experienced, and huge parts of the population need to be believed and supported."

Believing people means admitting that our communities are not currently as safe as we'd like them to be, and that's scary — but it's also the first step in helping them become safer.

If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, call the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit online.rainn.org.