Books

If You're Looking For Jane Austen Vibes With A Side Of Murder, This Is The Book For You

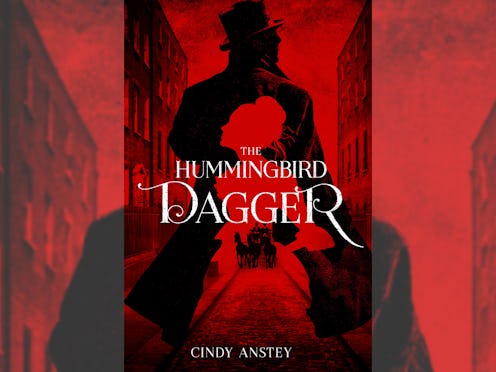

When you think of Regency Romance novels, the first author to come to mind is probably Jane Austen. If you're anything like me, you probably think of fierce heroines like Elizabeth Bennet, and love stories that are equal parts frustrating, romantic and totally obsession-worthy. What you probably don't think of? Murder. But it's this combination of the classic and the creepy that Cindy Anstey is bringing together in her new YA book The Hummingbird Dagger, due to hit bookstores on April 16, 2019. Bustle has the exclusive cover reveal and the entire first chapter below!

Here's a run down of the plot: The Hummingbird Dagger is set in 1833 and opens when the young Lord James Ellerby witnesses a near-fatal carriage accident on the outskirts of his estate. He doesn't think twice about bringing the young woman injured in the wreck to his family's manor to recuperate, but when she finally regains consciousness, she has no memory of who she is or where she belongs. The only clue to her identity is a gruesome recurring nightmare about a hummingbird dripping blood from its steel beak. With the help of James and his sister Caroline, Beth — as she takes to calling herself — slowly begins to unravel the mystery behind her identity and the nefarious circumstances that brought her to their door. But the dangerous secrets they discover could have deadly ramifications reaching the highest tiers of London society.

If that sounds right up your street, the cover below should definitely have you hooked. Check it out!

The Hummingbird Dagger by Cindy Anstey, $17.99, Amazon

And even though you'll have to wait until April 2019 to snag a copy for yourself, Bustle's got you covered with the entire first chapter of The Hummingbird Dagger below. You'll be counting down the days until you can start piecing together this mystery for yourself.

Before

The dark, narrow room was rife with the fetid odors of mold and decaying fish. The only light came from a slit high above her head. Beyond its insipid glow were shadows, some deep and inert, others blurred and in motion.

In this cell of unknowns, only the dagger stood out. It swung from hand to hand, side to side. Words accompanied each movement but the roar of panic obscured them.

All but the dagger ceased to exist.

Her eyes locked on its menacing beauty. The artistry was both simple and inspired, its form a study of opposites. The dark wood hilt gently curved into the shape of a hummingbird. The long bill that nature had fashioned to sip, man had fashioned to drink — to drink the nectar of life. And it was a thirsty bird.

Evidence of its last feed still dripped from the pointed steel beak. Dripped until it formed a red oozing puddle, small at first but growing steadily.

Blood. Her blood. She was going to die.

Chapter One

Disastrous Encounter

Welford Mills 1833

Guiding his horse to the top of a grassy knoll, young Lord James Ellerby toured Hardwick Manor and its grounds. He hadn’t gone far when he heard the scraping of wheels against stone, and he jerked around to witness a curricle emerge from the stableyard in a rush.

Walter, James’ younger brother, stood on the flimsy bouncing floorboard of a carriage, urging his horses from a trot to a run as he dashed pell-mell toward the manor’s gate. Walter wasn’t thinking of his safety or oncoming traffic. His friend, Henry Thompson, clung to the side-rail, looking anything but confident.

“Walter, stop!” James yelled, though he was certain the noise of the racing curricle prevented his words from carrying to the 14-year old boys. James’ heart pounded as he watched, fearing dire consequences. Had Walter learned nothing from their father’s accident and death a year ago?

Then James heard the jiggling equipage and thundering hooves of an approaching coach coming down the London Road. He turned to stare down the hill at the large vehicle as it sped toward the Torrin Bridge and Walter’s emerging curricle.

James shouted again, but to no avail. He was too far away.

As Walter’s carriage and the lumbering coach disappeared behind the trees, a great cacophony of crashes and screams rent the air. Heeling Tetley to a gallop, James’ heart pounded in double time. Within moments, he jerked to a stop in front of the bridge.

The road was empty, though the wind was filled with the high-pitched terror of the horses. Snippets of foul memories, flashed through James’ mind. He saw the ruined body of his father in the wreckage of a different accident, his neck bent at an impossible angle.

In near panic, James called again. “Walter! Henry?” Guiding Tetley to the edge of the road, he looked down into the gully.

Walter’s curricle sat to the left of the bridge at an awkward angle but still on its wheels. The boys were wide-eyed and motionless on the bench, but otherwise appeared unharmed. The horses stood at the edge of the river. The shrill sounds of their distress abated as Henry crooned soothing words of comfort.

Walter looked up, meeting James’ gaze. The color slowly drained from his brother’s face and he swallowed convulsively. “I… umm… I…”

James exhaled a tortured breath and then huffed in relief. He wanted to shout, pummel and hug his brother all at the same time. Instead, he turned Tetley to the opposite, considerably steeper, bank of the Torrin.

The momentum of the near collision had propelled the larger carriage down the slope on an angle. It had almost overturned and now hung precariously. Mire covered the doors. The coach’s horses were knee deep in water but, other than being spooked, looked fine.

And then, James saw a figure on the ground — a very still figure. His stomach clenched, and he jumped from Tetley, barreling down the slope.

And then, James saw a figure on the ground — a very still figure. His stomach clenched, and he jumped from Tetley, barreling down the slope."

A young woman lay on her back in the shallows of the river. Her face was pale, and long strands of brown hair floated beside her. James’ view was partially obstructed by two squatting men at her side. One was only visible from the back. His great coat dropped from his broad shoulders to blanket the mud. The other man had a smudge of blood smeared across his cheek; his face was unremarkable except for a scar on his chin.

Stepping forward, James’ path was suddenly blocked by the coachman. The man’s pockmarked face was flushed with suppressed anger and resentment, his black and gray peppered head jerked in agitation.

“Is she all right?” James asked, indicating the figure in the water.

The coachman stared past James to where Walter and Henry watched from the roadside. His eyes narrowed. “Not to worry, Sir. Her’ll be right as rain in a tic.” His harsh tone contrasted sharply with the reassuring words. He didn’t even look toward the poor unconscious young woman. “I needs ‘elp rightin’ me coach.” He continued to stare at the boys in undisguised animosity. “The sooner we gets this here coach of mine up, the sooner I can gets her to a doctor.”

Glancing at the figures by the water, James nodded. “Time is of the essence.” He turned back to his brother. “Get down here!” he shouted, trying to instill authority in his tone. He pointed to the far end of the coach deeply embedded in the mud. “When I say so, push. And push hard!”

“Hitch your horses to the back,” he told the coachman. A lord expected compliance even if he was only 20 years old and newly endowed with authority. “And get her out of the water!” he shouted to the men by the river.

At first, the men showed no signs of hearing, then without rising, one leaned over and slowly pulled her closer to the shore, into the mud.

“Is she alive?” James asked. The words almost stuck in his throat. Memories of his father’s broken body churned his mind yet again.

“A’ course, sir.” “Who is she?”

“Don’t know.” The bruised man stood. “She got on at the Ivy in Ellingham. Didn’t exactly introduce herself.” He turned to the coachman. “Hurry up, man.”

The coachman bristled. He had already unhitched the horses and rigged a line to the back of the coach. “You could always get your arses up here an’ ‘elp!”

The bruised man looked at the coachman with something akin to disgust, though he did take a position opposite to James, behind the coach door. The other man stayed by the water, nominally watching over the injured young woman.

James anchored his hands and shoved his shoulder against the filthy coach. His face was so close to the wood that he could almost taste the paint. Sweat trickled down his nose. He took a deep breath as much from disquiet as to prepare for the weight of the large coach. He shouted and the four men pushed while the coachman bellowed and pulled at his horses.

The coach was old and top heavy. Bandboxes and trunks clinging to the back added to the burden. The horses, nervous and fatigued, were almost at their limit. Then James felt a budge, a slight movement upward. James strained further and yelled to the others to push harder until, at last, the coach defied gravity and came to a standstill on the crest of the road.

Leaning over, hands resting on his knees, James gulped at the air trying to regulate his breathing. Suddenly, the road was a hive of activity as half a dozen field hands converged on them.

“You needs ‘elp, Lord Ellerby?”

“Yes, Sam.” James nodded as he straightened. “Could you get the team hitched? They need to get to a doctor.”

The coachman frowned at the good Samaritans and yanked the reins from Sam’s hands when the laborer picked up the leathers. Incensed, James was about to deliver a set down, when he was distracted by the sounds of wheels on gravel. A grocer’s cart appeared on the far side of the bridge.

“Lud, Mr. Haines, am I glad to see you,” James said as the small wagon drew up beside him. He leaned over the edge, assessing. Not big, but big enough. “Might we ask your help?” At Mr. Haines’ nod, James motioned to Sam and another hand, Ned. “Clear room in the cart.”

“No, sir. I be almost done.” The coachman tried to block their way.

James sidestepped, slid back down the riverbank and elbowed the ineffectual men out of the way. With one arm behind the injured woman’s knees and the other under her shoulders, James lifted slowly and gently. She was no weight at all. James noted the dark red stain growing in her hair and across her forehead. It flowed freely, dripping on his boots.

His belly clenched. This did not bode well.

The bruised passenger dogged his heels. “We will take her now.”

James ignored the man. He gently lay the young woman down among the carrots and cabbages. Shucking off his coat, he covered as much of her as he could. “Take her up to the manor, if you would, Mr. Haines. I will be right there.”

He turned back to the boys. “Walter, ride over to Kirkstead-on-Hill. Get Dr. Brant.”

Brant was the only person James would trust with this dire a situation, someone trained as a physician and a surgeon. It didn’t matter that Brant had only been in practice for a year; he knew what he was about and he was a good friend.

Walter jumped onto the seat of his curricle. Henry, mud and all, leapt up beside him.

Walter turned the grays and hurried down the London Road. “Drive sensibly,” James shouted after them, likely to no avail.

The coachman was livid. “Y’ve no right, sir! To take away me fare.”

“Your fare could die before your next stop. She needs immediate medical attention.” James tossed a sovereign at the callous man. “That should cover the remainder of her fees.”

The coachman caught the coin easily enough but looked far from pleased.

“Sam, you and Ned get her trunks off the coach,” James instructed, “and bring them up to the manor.”

James mounted his horse and galloped after the wagon. He quickly caught up to the lumbering cart as Mr. Haines negotiated the drive with diligent care but no speed.

James pulled Tetley to a walk.

In the full sun, he could now see the woman more clearly — she was young, perhaps 18 or 19. Her face was smudged with dirt and covered with cuts and bruises, so much so that it was hard to discern what she really looked like. Her dress was ripped and soiled beyond repair. Her bodice was soaked, adding the possibility of a chill to their worries.

In the full sun, he could now see the woman more clearly — she was young, perhaps 18 or 19. Her face was smudged with dirt and covered with cuts and bruises, so much so that it was hard to discern what she really looked like. Her dress was ripped and soiled beyond repair. Her bodice was soaked, adding the possibility of a chill to their worries."

James sighed with impatience and concern — a contrary combination. He reached over and tucked the corner of his coat under her side. She did not look well.

“I will ride ahead, Mr. Haines, and get the household ready for her.” James nudged Tetley with his heels. He didn’t need to get the household ready as much as he needed to solicit his sister’s help.

At the manor James tossed his reins to the groom and headed into the main hall.

“Where might I find my sister, Robert?” he asked the footman as the door opened. Feeling besieged, James almost wished his mother were here to consult… almost. Lady Ellerby had not yet regained her equilibrium, which was tenuous at the best of times, since his father's passing. Fortunately, she was in Bath visiting her sister and not due to return until the end of June.

“Miss Ellerby is in the garden, sir. I believe she took her colors out there,” Robert replied.

James nodded and quickly walked to the back of the hall and into the saloon. His wide gait sped him across the floor of the large room, and then through the French doors to the patio.

At 18, Caroline was two years his junior and, unlike Walter or his lady mother, of a steady, if somewhat unconventional, character. James had always relied on Caroline’s good sense, never more so than his first year as Lord Hardwick. Just out of mourning, Caroline’s yellow gown was easy to spot through the misty green lace of the new foliage. She was at her easel, not far from the sheltered arch of the conservatory.

“There was an accident on the London Road,” James said bluntly when he finally reached her side.

Caroline put down her brush and turned toward him. If she was surprised to see him covered in mud and without a coat, she showed no signs of it. “Was anyone hurt?”

“Yes, a young woman riding the London coach. With,” he added in a tight voice, “no one to see to her welfare.” The soiled, sodden face came to mind once again, constricting his breathing.

“Badly? Was she hurt badly?” Caroline frowned.

“I do not know. Mr. Haines is bringing her in his cart and Walter is fetching Brant.” “Walter? Is Walter involved?” Caroline stood and started toward the manor.

James followed. “I am afraid so. But he is fine. Even his ridiculous curricle is undamaged.” “That is almost too bad.”

James chewed at his lip and nodded as he stepped through the door directly behind his sister.

Mrs. Fogel and Daisy were in the front hall observing the mud tracked across the tiled floor when Caroline interrupted their conversation. “Mrs. Fogel, Mr. Haines will be arriving at any moment with a casualty — a passenger from the mail coach. Could you prepare one of the maid’s rooms? Perhaps, Daisy, you could move in with Betty for a few days. Yes, I’m sure that’s what Mother would recommend… if she were here.”

No sooner had Mrs. Fogel rushed away to carry out her instructions, when James heard the squeak and rattle of the cart as it pulled up to the kitchen door. Help ran from every direction.

Caroline shooed all but Robert and Paul, the groom, back to work.

“Poor girl. She does not look good,” Caroline said as the men carried the young woman up the backstairs and placed her carefully on the bed in one of the maid’s rooms. She lifted a lock of hair that had fallen over the young woman’s bruised and bloody face. “She took quite a knock.”

Caroline sat on the edge of the bed. “Do not worry, dear. We will have you to rights in no time. Dr. Brant is an excellent physician.” She patted the motionless hand as if the young woman could hear her.

James watched silently from the doorway, praying his sister was right.

By the time Caroline heard activity on the stairs, she had begun to clean the young woman’s rough, bruised hands. She could only imagine the difficult life this girl, not much younger than herself, had had to live. When Dr. Adam Brant entered the room, he hurried past James with a perfunctory nod, almost filling what little space remained. A tall young man, he bent over to accommodate the slant of the roof.

“Thank you for coming so quickly, Doctor.” Caroline backed away from the bed to give him room.

“She does not appear to have broken anything.” Dr. Brant said after preforming his examination. He opened his mouth as if about to speak and then closed it, shaking his head at some internal thought. Finally, he spoke. “While this,” he indicated a cut on the young woman’s right jaw, “looks nasty, this,” he pointed to the wound on the side of her head, “might be a worry.”

Caroline swallowed against the sudden lump in her throat and turned to meet James’ troubled gaze. She offered him a tepid smile of reassurance and then turned back to watch as the doctor dressed the patient’s gashed jaw. From the corner of her eye, Caroline watched James slip from the room. His expression was grim and determined.

Caroline swallowed against the sudden lump in her throat and turned to meet James’ troubled gaze. She offered him a tepid smile of reassurance and then turned back to watch as the doctor dressed the patient’s gashed jaw. From the corner of her eye, Caroline watched James slip from the room. His expression was grim and determined."

“I don’t believe she has a broken head,” Dr. Brant told her, “but we will not know for certain for a few more hours. Her pupils seem to be reacting to light, though it is hard to tell in this bright room.” Dr. Brant looked over at Caroline. “I can wait with you, if you wish.”

Caroline left Daisy, whose room had been commandeered, to tend the patient and led Dr. Brant downstairs to the front of the manor. As they neared the central hall, they could hear a loud voice issuing from the library. Although James’ words were indiscernible, his tone was not.

Walter was being taken to task in no uncertain terms.

Embarrassed by the emotional display, Caroline steered Dr. Brant towards the drawing room. “Perhaps we should wait in here.” She turned to the footman. “Robert, let Lord Ellerby know where we are, please. When he is free.” She quickly closed the doors. The heavy oak did its job; the echoes of anger were now muffled and almost inaudible.

“James will be here in a moment.” Caroline said needlessly. She led the physician to the settee and perched on the seat of an adjacent chair, pretending to be oblivious to the tension emanating from the library.

She sighed, feeling badly for her brother… her older brother. Being the disciplinarian was a new role for James — one in which he took no delight. But Walter had to be reined in, held accountable for his actions. For too long, he had run amok — coddled by their mother.

Caroline was certain that James would not lose the argument this time when their mother returned. Come September, Walter would be returning to Eton.

* * *

“What were you thinking?” James asked. His words and tone might have been a tad loud as the question echoed around the room. Doing his best to temper his anger, James took a deep breath. While relaxing his stance, he tried to emulate his father’s most severe expression. “There was no sensibility in the way you were driving, no propriety or modest behavior. All of which you promised!”

“Give over, James. It wasn’t my fault…not really. The road is seldom travelled. How was I to know that the London coach was there?”

“Right,” James said with more than a hint of sarcasm. “It’s only lumbered down the road at the same time every day since before your birth…. But how could you have guessed that today, of all days, it would do so again.”

“I couldn’t!” Walter glared at his brother for some minutes.

James stared back, giving no quarter. If he were not stern and unyielding, Walter would take advantage, pushing the limits, denying James’ authority again.

Finally, Walter lowered his gaze to the floor. “I should have been more cautious.”

James waited; hoping for an apology or a promise to never again race down a road without checking first. But there was none. No apology, no promise. Instead, Walter lifted his eyes, his expression was of derision; his mouth was partially open — a scathing comment waited at bay.

James waited; hoping for an apology or a promise to never again race down a road without checking first. But there was none. No apology, no promise. Instead, Walter lifted his eyes, his expression was of derision; his mouth was partially open — a scathing comment waited at bay."

James could see the strain on his brother’s face as he fought the urge to argue, to shout that James couldn’t tell him what to do. It had been Walter’s contention since their father’s demise.

Hardly the truth, but the truth hardly mattered.

The stand off continued far beyond what was necessary but, eventually, James considered his point made. Walter no longer looked defiant and had stopped arguing.

Moments later, James crossed the hall to the drawing room. Walter shuffled in behind him, his shoulders bowed and his eyes glued to the floor. He crossed the room and sat down — well away from James.

“Sam and Ned left a trunk in the hall, Caroline,” James said. “Where should it go?” Caroline frowned. “Trunk?”

“The young woman’s — from the coach.”

“Oh, of course.” She turned to the footman who stood by the door waiting for instructions. “Take it to the storeroom for now, Robert. Keep it to the front though. I am sure she will want her things as soon as she awakens.”

There was a brief silence after the door latch clicked.

“So, what have you been up to lately, Brant?” James asked, hoping to lighten the atmosphere. He knew he could count on his friend for florid and diverting anecdotes, something to keep Caroline distracted.

He, on the other hand, was restless and took a post at the window. There was nothing to see, nothing to watch except a large coach that lumbered down the road in the twilight hours. If James hadn’t known better, he would have thought it to be the London stagecoach.