Life

What Tennis’ First Equal Pay Push Can Teach Us About Gender Equity In Sports Today

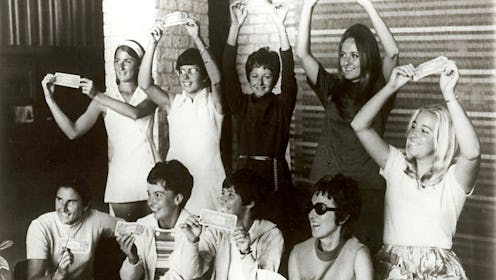

There shouldn’t have to be a “debate” around equal pay in sports, but somehow, female athletes are consistently paid less than their male counterparts, even in 2019. These disparities, as frustrating as they may be, are nowhere near what they were 30 or even 10 years ago. And lot of the strides gained today can be traced back to a landmark equal pay moment that happened in Houston, Texas, on September 23, 1970: Nine female tennis stars — facing the prospect of playing in a long-running tournament in Los Angeles, knowing male winners would receive prize money eight times larger than theirs — signed symbolic $1 contracts in order to compete in the tournament that would lay the foundation for the creation of the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). Led by World Tennis Magazine publisher Gladys Heldman and Billie Jean King, tennis' Original Nine, as they’re called, faced massive sexist backlash from the mainstream tennis industry and the press, but their actions paved the way for equal pay and opportunity in tennis.

“They were called not a boycott, but a girlcott,” Peachy Kellmeyer, the first full-time employee of the WTA and tour director, tells Bustle.

“It was those women who showed us [how to] stand your ground and ask for what you're worth,” Micky Lawler, the current president of the WTA, tells Bustle.

To understand the significance of this girlcott, it helps to go back to the first days of prize money in tennis. Surprisingly, this only happened in 1968, when the French Open became the first Grand Slam to open its doors to both pro players and amateurs, which helped standardize how tennis players would be paid for their wins. “As soon as that happened, the women began to be squeezed out,” Julie Heldman, Gladys Heldman’s daughter and one of the Original Nine, tells Bustle. This came to a head when the 1970 Pacific Southwest Championships announced the amount of the men’s purses — and it turned out they were eight times larger than those for the women.

Heldman recalls that Billie Jean King, Rosie Casals, and Nancy Richey, three of the top tennis players in the world, approached her mother asking what to do about this blatant disparity. “Within a couple of days, she had put together a tournament just for women in Houston, which was going to be called the Houston Invitational,” Heldman says. “But the night before the tournament was due to start in Houston … some bigwig at the United States Lawn Tennis Association [now the USTA] called every one of the players and said, ‘If you compete in the Houston tournaments, you will be suspended.’ And being suspended was a big deal — it meant you would not be able to compete anywhere.” In addition to Heldman, King, Casals, and Richey, the Original Nine was made up of Kerry Melville Reid, Judy Tegart-Dalton, Jane Bartkowicz, Valerie Ziegenfuss, and Kristy Pigeon.

The idea for the $1 contracts was to get the players out from under the auspices of the USLTA, so that they could continue competing (and winning prize money) without the association’s oversight. But that also meant not having the support of the major governing body of U.S. tennis — and in fact, it meant they would face direct opposition from the organization. Ultimately, the players had to put in a lot of work themselves.

“When we went to different cities starting in ‘73, [the USLTA] would direct their officials not to officiate in our tournament, and we would have to go out and find [our own] officials,” Kellmeyer recalls. At the beginning, they didn’t have communications staff, or even trainers. “We would sit down at the end of the tournament and do the draw for the next week together. We had our own little ranking system that we did each week and no rule book.”

“These women ... they swept their own courts, they sold their own tickets, they did their own radio shows, they did everything to grow the sport,” Lawler says.

Heldman remembers having to show face at sponsors' cocktail parties and teach tennis lessons to bolster awareness. "Every time there was any possibility of getting press, we would go do that.” She adds, laughing, “It was a serious chore.”

On the other hand, we all had to look the other way because we made a deal with the devil.

And a lot of that effort took place behind the scenes.

“[Gladys] is often forgotten,” Kellymeyer says, but “without her, there wouldn't be the Original Nine.”

“Once the women's tennis revolution came about, it meant that my mother had two more than full-time jobs,” Heldman says. “She frequently worked through the night. She was on the phone, she was on her typewriter. She was just doing one thing after another. It was beyond extraordinary what she pulled off.”

Part of what Gladys pulled off was securing a sponsor for the tournament through her friend Joseph Cullman, then the CEO and chairman of the board of tobacco company Phillip Morris, which is how it became known as the Virginia Slims Circuit. (It was formally incorporated as the WTA in 1973.)

“The sponsorship and Virginia Slims was critical,” Kellmeyer says. “You need money to get it off the ground. And they provided that.” The money from Virginia Slims provided uniforms, by designer Ted Tinling, as well as court staffing and more.

“We were all immensely grateful. [Phillip Morris] brought an incredibly high-end marketing presence for our tournaments,” Heldman says. “I do not believe that we would have been able to succeed without their money and their marketing. ...On the other hand, we all had to look the other way because we made a deal with the devil.” Heldman personally refused to wear the Tinling-designed dresses, which featured an insignia of a woman with a tennis racket in one hand and a cigarette holder in another, though she says no one else made the same decision.

“People didn't know the consequences” of smoking in the ‘70s, Kellmeyer says, though Heldman disputes that. “Virginia Slims never encouraged or used any of the women directly in cigarette ads. ...Tobacco has been a major health issue and continues to be, but quite frankly, it was done so professionally that we didn't really focus on that at the time.”

There were other complications, too. “My mother became fairly radicalized from dealing with the men,” Heldman says. Despite her mother’s credentials in the tennis community as a longtime promoter and publisher of World Tennis, Heldman says that she received an astonishing lack of support. “You would have thought that somebody who had been some version of an outcast would have stood up for us, and no one did. None of the men that we were seeing in the tennis world were standing up for us,” she says.

Heldman also says that her mother could be “emotionally incapable of functioning sometimes,” and even emotionally abusive throughout Heldman’s childhood. “She showed empathy with the players and for what was happening on the tour, what she was making happen. But not for me.” Heldman, who lives with bipolar disorder, had attempted suicide prior to joining the Original Nine, and says that that significantly impacted her experience of this moment in history.

You could understand why in an era when women had so far to go, we became a symbol

To be part of this moment in tennis was also a crash course in feminism. “In the beginning, we didn't think of ourselves as feminists,” Heldman says. “We were out there trying to make this thing happen, but fairly early on we were viewed by some people as sort of forerunners of this wave of the women's movement.”

“What they wanted was for any young woman who was talented enough, that she could make a living playing women's tennis,” Kellmeyer says. “It was a time that you weren't afraid to do anything that you didn't, you felt like you could do whatever you wanted to,” Kellmeyer says. (It’s worth noting here that in 1973, Kellmeyer brought a lawsuit that ended a prohibition against female students being awarded athletic scholarships; this case is widely thought to have paved the way for Title IX, legislation that prohibits sex discrimination in educational settings.)

“You could understand why in an era when women had so far to go, we became a symbol of some things,” Heldman says.

This era in tennis quite literally changed the game — for tennis and for women’s sports as a whole. The famous $1 contracts preceded the famous Battle of the Sexes match, where King beat Bobby Riggs in 1973, the same year the U.S. Open offered equal prize money for the first time. “That Bobby Riggs, Billie Jean King match in my own memory was sort of like landing on the moon,” Lawler says. Still, equal pay in the Grand Slams wasn’t fully achieved until 2007, when Wimbledon paid Venus Williams the same amount as Roger Federer won.

“It's great to see the young women athletes who at one time were looked down upon as being tomboyish, who are now the most popular athletes in the world,” says Kellmeyer. “This past U.S. Open was one of the most exciting for women that I've ever seen.” But, she adds, “The one thing that we've learned, if nothing else, is there's still a long way to go.”

And, as the summer of U.S. Women’s soccer’s high ends, that goes for other sports as well. “Women's tennis has always been the most successful women's sport,” Heldman says, thanks to the big names and giving players of any gender equal airtime. “We see that women's sports coverage on TV is not anything near what men's sports are,” Kellmeyer says. “There's still a need for more opportunities for women.”

Lawler says that because tennis is the "case study of success" for equal pay in sports, other elite leagues have a lot of work to do to create the same level of equity. This can include putting men's and women's games on the same stage, as Grand Slams and Olympics do, or by promoting women's games with the same enthusiasm as men's. These measures and others can help increase viewership of and revenue women's sports — paving the way for equal pay. "Tennis does keep pushing everybody else forward," Lawler says, "and everybody else is now in a place where success breeds success."

“The openness to women's professional sports is here,” she adds, “and it's only going to get better and better.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misidentified the Pacific Southwest Championship, the Virginia Slims Invitational, and the location of the championship where Peachy Kellmeyer was the first referee. It has been updated to include the correct information.

This article was originally published on