Books

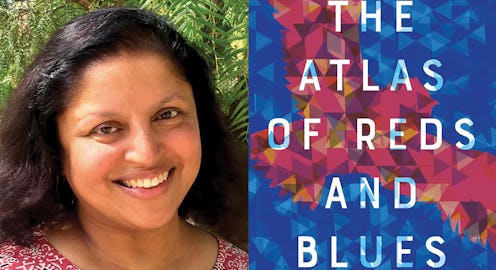

This Must-Read Novel About Racism Is Inspired By The Author's Terrifying Real-Life Experience

In 2010, agents from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation raided Bengali American poet and fiction writer Devi Laskar's home. Her husband, a professor of electrical engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology, was accused of misusing university resources for his startup, though the case was later dismissed. Devi Laskar was, she says, weeks away from completing a novel when the agents confiscated her personal laptop in the raid. They never returned it, and the novel, which was stored on its hard-drive, was lost, but the frightening experience of the raid planted the seed of what would later become Laskar’s debut novel The Atlas of Reds and Blues.

"I was not shot, but there was a raid and they pointed a gun at me," Laskar tells Bustle. "It's true that when someone is pointing a gun at you, you see your entire life flash before your eyes. And so I played with that conceit. I wanted to piece together in my mind: What if this happened to my character? Why would she think it had taken place?"

A year after the raid, Laskar revisited a short story she had originally written in 2004 for a Squaw Valley workshop about a dog, children, and some unpleasant new neighbors. She used the short story and other bits and pieces she had written over the years as the foundation of the story of The Atlas of Reds and Blues. The novel reimagines the day of the raid with one crucial difference: What if she had resisted the officers? What if she had been shot?

"I wanted to piece together in my mind: What if this happened to my character? Why would she think it had taken place?"

When The Atlas of Reds and Blues begins, "Mother," the protagonist, has been shot by the police and lies bleeding on her driveway. Mother and other characters aren't given personal names, both because they are "invisible in America" and in order to pay homage to the Bengali tradition of using titles like "Baby Sister" within the home. Throughout the book, readers careen back and forth through time, bearing witness to Mother's memories: her childhood as a Bengali American girl growing up in the South, her early career as a reporter, her marriage to a busy white man, and her life as the mother of three daughters.

Each flashback — written in accessible but poetic prose — is a glimpse into Mother’s life. Laskar’s use of vignettes to comment on weighty topics like racism and sexism recalls Sandra Cisneros's The House on Mango Street more than it does the fiction of fellow Bengali American authors like Bharati Mukherjee, Jhumpa Lahiri, and Chitra Divakaruni. Like Cisneros, Laskar varies the tone of her vignettes; some are sad or angry while others are humorous, and their power is collective.

Initially, the novel's plot mirrored the author's own journey. Later Laskar realized that an autobiographical approach would detract from her protagonist's journey. She decided to cut events that had happened after the raid from the novel, so that she could fully explore what had led up to the event. The author is quick to explain that none of the racist incidents in The Atlas of Reds and Blues are "verbatim"; they do not exactly reflect events that happened to her or people she knows. It's a testament to Laskar's devastating storytelling that every incident reads true anyway.

Laskar was born and raised Chapel Hill, "a blue dot in the red state of North Carolina," she says. Inside their home, her immigrant parents kept Bengali customs, but when the family walked out the front door, they knew they were in America, and they treated their walk to the bus stop serving as a "transition period." It was in college that Laskar first felt comfortable talking about racism openly because "there were enough people of color around me, there were enough black people around me, where we could have a discussion. It wouldn't necessarily be a productive discussion, but at least we were talking."

Laskar hopes that The Atlas of Reds and Blues can broaden conversations about racism. "I felt compelled not to let anyone off the hook," she says. "I just wanted to be transparent that this is wrong. Unless we actually have a dialogue, it's not going to change. I have kids. I'm terrified for my kids." In the book, Mother and her daughters tacitly agree not to talk about the racist incidents they face in order to protect "Daddy," who is white. Laskar says that Mother is unwilling to burst Daddy's bubble because "if he realized how bad it was, he wouldn't be able to leave and do his job." Although the characters don't discuss racism, a reader can observe that it's the unspoken daily accumulation of degrading racist incidents that brings Mother to an emotional boiling point — a point of resistance that results in her being shot.

"I felt compelled not to let anyone off the hook," she says. "I just wanted to be transparent that this is wrong."

Racism against Laskar's Bengali American characters is bound up with anti-blackness rather than xenophobia. Mother remembers a moment from her childhood when a fellow student assumed she was dating another student because he was Black. Mother mentally notes that his skin color is coffee with cream and says, "I'm not Black." The fellow student responds, "Sure you are... You're not white." The fellow student notes that another boy would never ask The Real Thing to "go with him." When Mother asks why not, the student touches her skin "creating a crater of shock," and says, "Because... this doesn't rub off."

Although it recounts ugly racism, the novel is marked by beautiful, lyrical repetition. Laskar considers herself a poet first. Even the book's structure is inspired by one of Laskar's favorite poetry forms, the pantoum, a Malayan folk poem. In a pantoum, a phrase is repeated throughout, but subtle changes in meaning occur due to different contexts. She says, "This book is one giant pantoum because the beginning is the end, and she's considering things over and over."

One repeated, almost satiric element in The Atlas of Reds and Blues is the phrase "Bless your heart," intended to absolve a speaker of ignorance or cruelty. Laskar observes that in the South, "white Southerners "tack on 'Bless your heart' as the magic dust that makes a statement OK. You're saying something mean like 'She can't dress herself to save her life,' but then you say 'Bless your heart.'"

She says, "This book is one giant pantoum because the beginning is the end, and she's considering things over and over."

Another element skillfully repeated in the book is eerie doll imagery. At one point, Mother remembers getting into a car accident in which a brown doll that nobody else wanted hits the windshield along with her, and loses her head. The narrator says, "Like children, most dolls are made only to be seen, put on display. Real live dolls are taught to remain stoic, bear witness in silence, no matter how the consumer judges."

Laskar remarks on the impossible proportion of the iconic Barbie doll. The doll imagery in The Atlas of Reds and Blues is intended to challenge the minority myth and its unattainable standards. She explains that the common perception of Asian Americans is: "You all do well in school, you're really quiet, you pay your taxes, you want to be American, you assimilate." She laughs gently and shakes her head. "And I was poking at that a little," she says. "Well, no... actually not."