Books

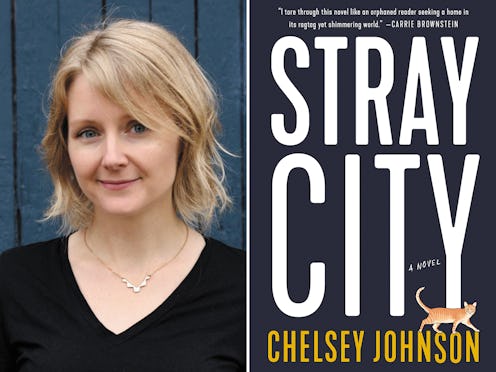

Why 'Stray City' Author Chelsey Johnson Wrote A Queer Novel That Isn't A Coming Out Story

When Chelsey Johnson sat down to write her debut novel, she knew she wanted to write a queer book that wasn't a coming out story.

“For a long time, if you ever tried to rent a gay movie — especially in movies but also in books — we always got the coming-of-age story, which was always a coming out story,” Johnson tells Bustle. “I wanted to write a coming out story that went the other way, which to me sounded equally scary and painful. If you’d spent a lot of time and emotional capital and familial strife establishing this queer identity, what happens when you kind of backslide, and go the other direction? It’s just when you think you’re about to lose something that you realize just how much it means to you or how hard-fought it was.”

Twenty-four-year-old Andrea Morales, a lesbian living in Portland, is at the center of Johnson’s debut novel, Stray City. Andrea has spent years growing into her identity, even against the wishes of her family. But her life takes a turn when, in the wake of a bad breakup, she sleeps with a man, Ryan, gets pregnant, and decides to keep the baby — much to the confusion of her community in Portland.

Stray City by Chelsey Johnson, $16, Amazon

The inspiration for the novel actually began with Ryan, who was stuck with a cat in a van in Bemidji, Minnesota in a short story Johnson was polishing. The author toyed with the idea that he'd left a tragic girlfriend behind, but that direction didn't really grab her attention. She wondered: What if that woman was a lesbian? Suddenly she had all these questions. How would such a relationship happen?

"When you do something that isn’t expected, it clarifies what people did expect, and the gap between who people think you are and who you really are, that’s where I think your real self actually resides, in that gap. And that’s also where stories happen," says Johnson. "That’s just the kind of thing I think you’re hungry for as a reader, and I think is your ongoing hunger in life too, to figure out what’s going on in that space."

The novel circles a very vulnerable moment in Andrea’s life, a time Johnson describes as one of "both possibilities and terror." "Creatively, there’s this wide-open life ahead of you and you don’t know," she says. "There’s that feeling both of anything could happen, and, 'How on Earth am I gonna make things happen?'"

One way Andrea deals with external pressures is by presenting different faces to the world — first in high school, when she discovers her identity as a lesbian for the first time, then in the Portland Lesbian Mafia, when she hides her flummoxing, endearing, complicated explorations with Ryan.

"This is such a classic queer thing," Johnson says. "And not just queer; code-switching happens across all kinds of identities. But speaking to my own experience and to that of many gays I know, you learn really young to split, to have this double self, this double consciousness. W.E.B. DuBois coined that idea of the double consciousness for black people, the idea that you have one self that’s safe for the world to see, and that’s like your shield, and behind that you cultivate your real self, which stays protected by that false self until you’re in a space where it’s safe to come out.”

Although Stray City isn’t autobiographical, Johnson did draw on her own life and her love of Portland. The novel is a vibrant portrait of the city, so tactile you almost shiver in the fog and vibrate to the Riot Grrrl beats.

“It’s not so much this happened to me as this happened to everybody I knew. It’s full of truth that is not necessarily my personal truth,” Johnson says. “I wanted to show these lives and this community and this world that is and was very real and very present to me and my friends but that we never saw represented in mainstream narrative. I’m always really hungry for great queer fiction, and finally I felt like I could do this, I could make it myself.”

Johnson's vivid portrait of '90s Portland is a warm welcome to any reader who wants to escape to a world where being gay is the norm. "I wanted to defamiliarize heterosexuality and let the straight-identified reader maybe realize what it’s like to be the weird thing for once," Johnson says. Stray City adds to the conversation both by offering a very human story that goes beyond the coming out tale and in exploring the many ways people set restrictions around their sexuality.

“I think keeping in mind — and this goes for people across the spectrum, whether you identify as straight or gay or queer or whatever — there are so many options," she says. "You can change, you’re not stuck with just one thing. Straight people can be very rigid about gender and sexuality roles, but I think queer and trans people can be very rigid about gender and sexuality roles too. Nobody’s immune to it. Rules and structure can be really soothing but they’re also super confining. I think it’s a matter of remembering: there are other ways to do this, and people can do what they want.”

What does she hope readers walk away thinking about when they’ve finished Stray City? She pointed out there will be a few different kinds of readers who will come to this book. Straight readers have the opportunity to gain a new understanding of queer culture, but Johnson hopes that isn’t all they take away.

“I also want them to understand: I feel like queer people have much more visibility now in the culture, we’re much more present, but with the advent of mainstream acceptance in terms of gay marriage or gays in the military or whatever, I think sometimes people might have the idea that it’s easy now, or it’s not an issue," she says. "I think the book really gets at the roots of familial pain that are important for people to also get a sense of."

Johnson hopes queer readers come away "with the pleasure of recognition" of seeing themselves or their friends in art. "And then of course for young readers, I think of those books that blew open my sense of who I could be or what the world could be, and my wildest dreams are that people come away with a sense of that — that there’s more than what’s presented," she says.