Books

This New Thriller Challenges Our Obsession With Dead, Beautiful Women

Kitty Genovese. Chandra Levy. Elizabeth Short. Nicole Brown Simpson. You know their names, you know their faces, and because we live in a culture that fetishizes violence towards women and commodifies their deaths, you know every detail about their brutal, gruesome murders, too — but why exactly are we so obsessed with these beautiful dead girls? That is one of the questions author Maria Hummel explores in her new novel, Still Lives, the fast-paced feminist thriller about the L.A. art world you don't want to miss this summer.

An L.A.-based artist and provocateur, Kim Lord is about to premiere the most important exhibit of her career: Still Lives, a show of self-portraits in which she portrays herself as famous dead women. It is a collection she sees as “a tribute to the victims, and as an indictment of our culture's obsession with sensationalized female murders," and one the entire art world can't stop talking about, especially after Kim fails to appear at the Rocque Museum for opening night.

Everyone has their own theory as to what happened to the famous artist, including the museum's copy editor Maggie Richter. Some think it's just another one of Kim's publicity stunts — what better way to promote an art show about female victims than to become one yourself? — while others are sure it could be foul play at the hands of any of Kim's art world enemies. There is also plenty of suspicion towards up-and-coming gallerist Greg Shaw Ferguson, who just so happens to be Maggie's ex and Kim's new lover. When the police name him as their number one suspect, Maggie finds herself drawn into an investigation of her own that leads her everywhere through the dazzling city of L.A., and to the dangerous underbelly of the art industry. But the closer Maggie gets to the truth, it seems, the closer she comes to becoming the next victim, just another murdered woman for the world to obsess over.

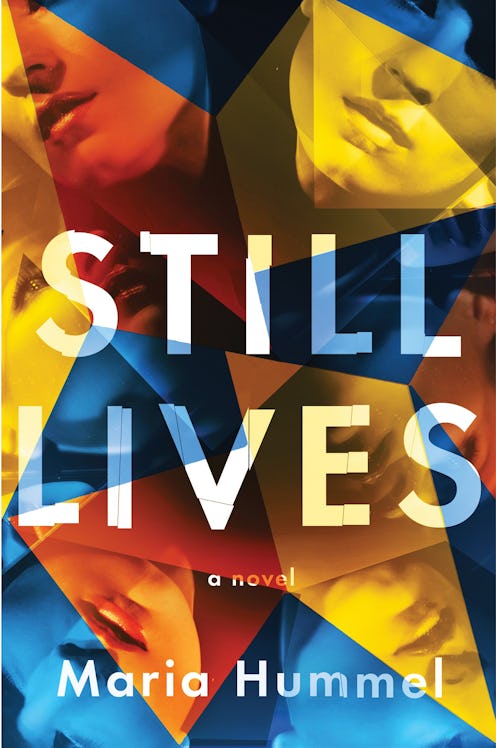

Still Lives by Maria Hummel, $21, Amazon

Still Lives is at once a gripping and entertaining mystery, and a biting cultural critique that seeks to understand our obsession with the violent deaths of beautiful women. As Maggie, the book's heroine and narrator, digs deeper into the mysterious disappearance of Kim Lord, readers will find themselves digging deeper into the book's even bigger question: why do we fetishizes the dead female form, and who loses because of it? As Maggie explains in the novel, "I suppose we knew what was coming with Still Lives — it would expose us, it would expose most women's oppressive anxiety about our ultimate vulnerability, a fear both rational and irrational, like the fear of the footsteps behind you at night, magnified a hundred times."

Reading Still Lives is like being frozen in that feeling of fear, like being stuck in that moment right before the mysterious stranger lurches out from the darkened alley to grab you.

Take Kim's exhibit, which is at the center of the novel: In each of the 11 paintings, the artist takes on the guise of well-known victims, including Roseann Quinn, Bonnie Lee Bakley, Gwen Araujo, Chandra Levy, Nicole Brown Simpson, Kitty Genovese, and Elizabeth Short, otherwise known as the Black Dahlia. Although each woman's murder is different and unique, Kim's portrayal of them — really, Hummel's description of Kim's portrayal of them — evokes an inescapable feeling that you, the reader, could be any one of them. As Maggie describes in a powerful passage in the novel:

"The paint thickens and thins differently around each of the figures, but the women's expressions all have the same eerie clarity, like they've been rinsed clean. They stare back into the galleries. Hard. The likeness flashes out — the way Kitty is also Gwen is also Rosann is also Kim. All are Kim. In each of the paintings exists a dead woman, identified by her hair, her eye color, her clothes and gestures, and also, inexplicable, Kim Lord, wearing that death, the way shamans of old donned the masks and cloaks of spirits."

The victims may be different, both in their lives and their deaths, but the way our culture reacts to them — first, with fascination and obsession, and later, by making them commodities — is all the same.

“I hate this artwork,” Maggie says while looking over Lord's exhibit, echoing the thoughts countless women have every day they are faced with another image or another story about a murdered woman. “I hate the abject powerlessness it projects. I hate it because it reminds me there is an end for women worse than death.”

Speaking for so many women who are bombarded day in and day out with graphic images and detailed narratives of brutalized, mutilated, and dead bodies that could very well be their own, Maggie wonders why the Still Lives exhibit has a place in the museum, or in the art world at all:

“Why here? Why subject us to these scenes in an art museum, when we’ve seen them practically everywhere else? For decades, the spectacle of female homicide has spattered the news [...] We’ve seen her and seen her and seen her. We’ve witnessed victims in every feminine shape, young to old. The child pageant winner and her sexy lipstick, duct-taped and garroted. The teenager abducted from her suburban bedroom. The old woman raped and strangled by a stranger she allowed in the door. What we haven’t seen, we’ve read or overheard. How could Kim Lord’s depictions move us beyond disgust and visceral fear, into an emotion that is deeper and richer, freighted with pain for humanity? It’s just paint around me now. Shape, texture. It’s also more.”

The news media, tabloids, television, movies, true crime books, even the world of high art — in every corner of our cultural landscape is the shadow of our obsession with murdered women. Our world is soaked in the blood of beautiful dead girls whose brutal ends we play and replay, over and over again, but for what? Is it for entertainment or enjoyment, or perhaps a lesson in morality? Still Lives doesn't just ask why we are obsessed with female murder victims. It also asks how: how we interpret violence against women, how we consume and commodify it, and how use it as tool of oppression.

As Maggie explains about one particular famous female victim,

"Roseann Quinn's 1973 murder exploded in the national news because it was a timey I-told-you-so to the new generation of women choosing sexually liberating lives. Quinn was a New York City teacher, she lived alone, and allegedly went out to bars a night and brought home men. One evening she made the wrong choice. She made the wrong choice. The headlines: NUDE and SLAIN. SEX and SLAYING. How important it was to use both words, in that order."

Still Lives is a electrifying mystery, one that crackles with suspense and intrigue. But it is not just an exploration of the shady underside of the L.A. art scene, or a warning about the dangerous combination of fame, money, and sex, and it is certainly not just a titillating tale about a missing woman. Like the fictional exhibit it was named after, Still Lives is an indictment of how women's bodies are treated by a society that is determined to control and consume them, and it's so much more than a story. Because when it comes fear, anxiety, violence, and abuse, as Maggie puts it, "It's not a story to us," it's an experience we face every day.