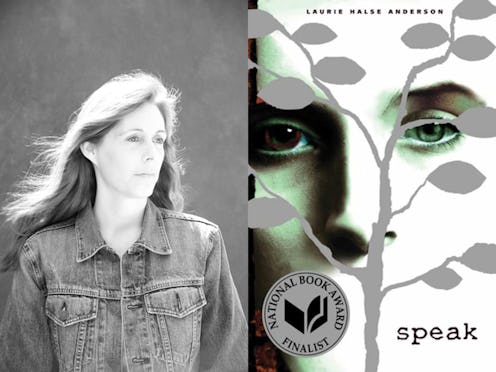

Books

This Book About Rape Culture Is Nearly 20 Years Old, But It's Still Too Painfully Relevant

If you came of age in the last 15 years or so, there’s a good chance you read Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson. Maybe it was assigned reading, or maybe you, in circumstances similar to mine, learned of it from a friend, who got it from her older sister, who borrowed it from a neighbor. It's a story about sexual assault and the trauma that comes afterward — and by the time it made its way to you, the book was probably a little tattered, permanently creased on the page that contained That One Scene you could never forget. You passed the book from girl to girl like a whispered secret, a practice round for what would become a grim reality as grown women.

When I tell Halse Anderson of how my friends and I secretly shuffled a tattered copy of Speak between us, she tells me it "warms her heart" — but "at the same time," she adds, "It wrecks me. That was how your group passed along knowledge of sexual violence and tried to protect each other."

Women have always devised ways to protect each other from dangerous men. These protections usually take the form of an exchange of knowledge, whether it be books, the names of men to avoid, or places you can go if you need help. In recent days, this informal information exchange has been given a name, "the whisper network," and more recently, a movement, #MeToo, has been born in the aftermath of the Harvey Weinstein scandal with the intent of making at least some this knowledge public in an attempt to draw attention to the problem, provide solidarity to women who have experienced trauma, and to appropriately censure those who should be held responsible.

"Whisper network" is concise and painfully apt term; sexual violence feeds on silence, a terrible fact that was true in 1999, when Speak came out, and remains true now. The novel takes that silence and makes it literal: The protagonist, Melinda Sordino, is raped by a high school senior at an end-of-school party she attends with her best friend, Rachel. Melinda calls the police, but everything goes wrong. "Someone grabbed the phone from my hands and listened," she says in the novel. "A scream — the cops were coming! Blue and cherry lights flashing in the kitchen sink window. Rachel's face — so angry — in mine. Someone slapped me." She walks home alone, ostracized by her best friend and everyone else at the party.

When she enters high school three months later as a freshman, her friends have abandoned her and she has no voice. Though she is not physically mute, Melinda barely speaks at all — not to her friends, not to her teachers, not to her parents, all of whom think her silence is just a way of getting attention. It's only at the end — when she finally tells Rachel the whole story — that she realizes she isn't alone. Rachel believes her, and she soon discovers that other women have been harassed and abused by the very same person. People she befriends throughout the novel hint at his reputation for abuse ("He's only after one thing," a friend tells her. "And if you believe the rumors, he'll get it no matter what.") Before she's able to publicly tell people about the rape, Melinda decides to do so via her own version of a "whisper network": a listing of dangerous men, etched on the wall of the girls' restroom. There, she writes, "GUYS TO STAY AWAY FROM," and scribbles her attacker's name. Later in the novel, she returns to the bathroom to find that other girls have left comments about the same guy: "He's a creep," one writes. "He should be locked up," writes another. "Call the cops," someone else warns. As Melinda learns she's not alone and discovers she has allies, she slowly works up the courage to tell her story.

"I think Speak is beloved because so many people — teen and adult — know what it’s like to be silenced, and understand the struggle of finding the courage to speak up," Halse Anderson says. "It is the perfect story to be passed hand-to-hand, because nothing can strengthen us as much as compassionate friends."

Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson

Joy Peskin, the Editorial Director of Farrar, Straus and Giroux Books for Young Readers, the publisher of Speak, is not the novel's original editor, but she still still remembers the first time she read it nearly two decades ago, shortly after the novel's release. "It was a moment that inspired a lot of reflection in me, like it probably does in all of its readers," she tells me. "That includes "people who think, 'This happened to me and I didn't know what to call it. I didn't know what it was or I haven't thought about it since it happened.' Or, 'This is a thing that happens to other people and maybe I didn't know about it, or '[I] didn't know how to talk about it.'"

Peskin has reread the book in recent years and experienced very different emotions — a shift she credits to the more nuanced conversations taking place about rape culture today. "Now when I read it, I feel not at all surprised that it happened," she says. "I feel like, 'Oh yes, of course. These are things that happen.'"

That, of course, is part of the reason Speak still remains so relevant: While the conversation about rape culture has shifted in many ways, rape culture still exists to be talked about. "It feels, in many ways, ahead of its time," Peskin says. "I mean Laurie [Halse Anderson] can speak for herself, but I don't think she would've, could've, or should've written it any differently than she did. I feel like these things weren't talked about as much then as they are now... but in a way it's a bit tragic that 20 years later, we're still talking about this and we're still having these conversations and it's still surprising to the world at large."

Both Peskin and Halse Anderson emphasize the importance of talking with young people, particularly boys, about the insidious yet overwhelming influence of rape culture in their lives. The power of Speak, Peskin argues, lies partially in the fact that it doesn't focus on the physicality of the rape, but instead addresses the systems that made the attack possible and kept Melinda silent afterwards.

"Part of the genius of Speak is that it doesn't start that night at the party. It starts after and we see this girl suffering, and it's not fun, and it's not OK and it's not cool," Peskin says. "The only way it can stop at a party like that is if the kids themselves stop it. I think that's possible. I don't think it's unrealistic, but first they have to learn that what they're doing is wrong."

In 2005, Laurie Halse Anderson addressed this in a novel about toxic masculinity, Twisted. She says she was inspired to write Twisted by the young men she met while on school tours for Speak, many of whom told her they couldn't fathom why Melinda was so upset about what they perceived to be a fairly normal social interaction: a girl dances with a guy at the party, she starts making out with him, she doesn't exactly say "no" to more.

"There is a lot of bullsh*t to unpack here," Halse Anderson tells me. In conversations, what jumped out at her was the lack of thought about what the girl wanted — and the idea that "rape is a logical extension of the other games of physical dominance that they’ve played their entire lives."

Peskin agrees that talking to young men is essential, particularly when it comes to examining consent and victim blaming. "I think one of the things that Speak did was turn on its head the idea of victim blaming," she says. "No one deserves to be sexually violated. Period. No matter what they're doing, what they're drinking, what they're wearing, how they're acting. Period. That's something that society still needs to learn. It's a conversation we still need to have. Maybe more so now than ever."

Speak: The Graphic Novel by Laurie Halse Anderson, Illustrated by Emily Carroll

Paradoxically, Speak, a novel about rape culture designed to start conversations to end rape culture, still continues to sell well. (So much so that a graphic novel adaptation, illustrated by Emily Carroll, is being released in February.) Yet, Laurie Halse Anderson is afraid too little has changed in the 18 years since Speak's release. "The victims of sexual violence are still held responsible for their attacks," she says. "Parents are still afraid to have ongoing, sensible conversations about human sexuality with their children. Too many schools hesitate to foster conversations about these issues, and too many police and judicial systems — largely run by men — ignore or belittle victims demanding justice. Until America’s adults really start talking about the sexual violence, rape culture, and consent, nothing will change. But I think that the #MeToo movement might be the beginning of that conversation."

Both Halse Anderson and Peskin say that #MeToo is the first time they've seen conversation about sexual assault on such a widespread level — the kind of conversations they have been waiting to see since Speak came out nearly 20 years ago. As writers and editors and readers, they both put a lot of stock in the power of books to change people's lives, and they're not totally off-base: a 2012 study showed that reading Speak actually helped kids better understand the intricacies of rape culture. Still, both women understand all too well that conversation is simply the first step.

"First and foremost, we need to affirm and support the people coming forward with their #MeToo statements and stories," Halse Anderson says. "After that? There is so much that can be done. I'd love to see college students have opportunities for real conversations and educations about sexual violence. I’d love to figure out what police departments and court systems are doing the best job enforcing the laws and supporting survivors. I’d love to see cultural leaders in film, television, music, comedy and sports step up and become change-makers."

"#MeToo is a very important tool for reducing the shame that silences so many," she adds. "But getting survivors to speak up is only the first step."

It has been many years since I first read that battered copy of Speak, but in all that time, I have never forgotten the final six words of the book: "Let me tell you about it." It was, and is, a persistent reminder that stories can change lives. But only if you do something about them.