Books

This Romance Writer Tried To Trademark The Word "Cocky" & It Didn't Go So Well

If you've been fretting over a replacement for the word "cocky" in your romance novel title ever since one writer attempted to block all other authors from using it this spring, fear not. According to a judge in New York, it is a "weak trademark," meaning you can still use "cocky" in your book title.

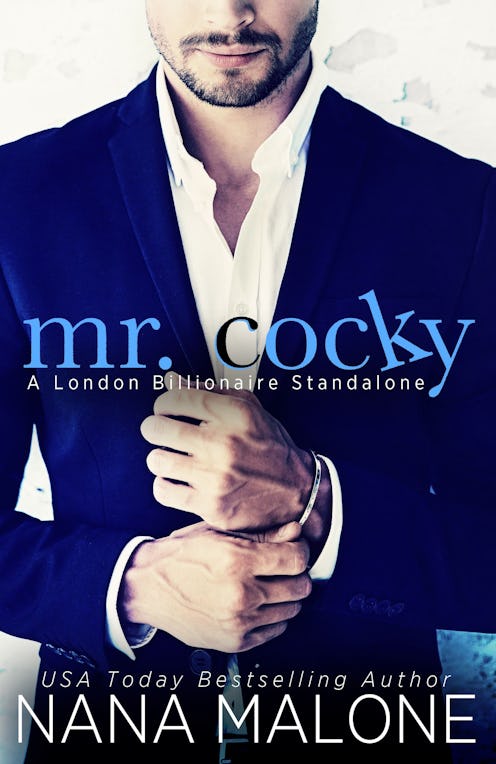

First, let's back up and figure out how we got here, to a court in New York city where one judge was left to decide the fate of "cocky" in romance book and book series titles: Back in Sept. 2017, author of the self-published Cocker Brothers books Faleen Hopkins filed an application with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for the title of her series, and for the use of the word "cocky" in any romance titles. Essentially, she was trying to prevent other romance authors from using "cocky" in titles. Her initial request registered the word as trademarked "without claim to any particular font style, size, or color" as of April 17, 2018.

In May, Hopkins began reaching out to authors on their social media accounts and via email to ask them to stop using "cocky" in their titles, and to rename any of their books on Amazon that used it. According to screenshots of the letters posted by several recipients, Hopkins's messages threatened legal action against the authors, and promised "if I sue you I will win all the monies you have earned on this title, plus lawyer fees will be paid by you as well."

Romance Twitter was not having it, and almost immediately, the hashtags #CockyGate and #SaveCocky began trending. Readers and writers chimed in to share their thoughts on Hopkins's trademark attempt, many of them expressing outrage, disappointment, and confusion. Several pointed out that preventing romance authors from using the word "cocky" would be like asking science fiction authors to stop using the term "star" or "galaxy," or telling crime writers to avoid the words "murder" and "mystery."

As an act of protest, several authors collaborated on a collection of stories titled Cocktales: The Cocky Collective. In response, Hopkins applied for a preliminary injunction and temporary restraining order that would prevent the book's publication. Her lawsuit named three defendants: Tara Crescent, the author of a book series that uses the word "cocky" in the title; Kevin Kneupper, a lawyer who filed a legal challenge against Hopkins's attempt to trademark the word; and Jennifer Watson, the publicist for Cocktales.

In response to the lawsuit, the Authors Guild and Romance Writers of America teamed up to provide legal assistance to those being sued, and to defend the principle that no one should be able to own the exclusive rights to use a common word in book or book series titles." Their argument stated that there were "countless romance novels" that used the word "cocky" in their titles before Hopkins's series and trademark, and that “cockiness (in all its permutations) remains as prevalent in romance novels as the use of stunning, scantily clad models on their covers”. It also explained that trademarking "cocky" and preventing other authors from using it would be "like an author claiming trademark rights in the word death as a series title for murder mysteries and suing anyone who used that word in the title of their crime stories."

The case was heard in a New York court on Friday by judge Alvin Hellerstein, who sided with the Authors Guild and Romance Writers of America. In his ruling, Hellerstein called Hopkins's trademark "weak" and said he believed romance readers were "sophisticated purchasers" who wouldn't confuse authors' books, despite similar titles. He also denied Hopkins's motion for a preliminary injunction and temporary restraining order against Cocksure and other books with the word "cocky" in the title. Kneupper was removed from the case, and will move forward with a separate legal challenge to Hopkins's trademark focused on the use of "cocky" in series titles.

“Authors should be able to express themselves in their choice of titles,” said the Authors Guild in a statement following the judge's ruling. “A single word commonly used in book titles cannot be 'owned' by one author. This is especially true when, as here, the word has already been in use by other authors in titles for years.”