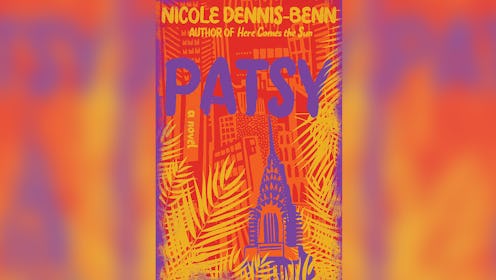

Books

This Is An Essential New Novel About LGBTQIA+ Identity, Immigration, & The American Dream

Immigration to the United States reminds Patsy of the Rapture. “People would leave ailing parents, spouses, and newborn babies if they have the opportunity to live and work in America,” she thinks, in Nicole Dennis-Benn’s new novel, Patsy. And Patsy would know: She has just convinced a U.S. immigration officer that if the visa she applied for is granted, the existence of her five-year-old daughter, Tru, guarantees her return to Jamaica. But, as readers already know, Patsy has no intention of returning to her country, ever. In fact, her daughter is just one of many things she's desperate to leave behind.

Documenting the disappointments and shattered illusions that immigrants — and particularly women immigrants of color — face in the pursuit of the American Dream, Dennis-Benn’s second novel will leave readers asking if that dream can still be realized and if it ever could be realized. Taking readers from Y2K to 9/11 to the election of Barack Obama, Patsy chronicles a decade of immense shift in American life, a time that could charitably be described as a rollercoaster ride for many immigrants, documented or otherwise.

Patsy herself arrives in the United States in 1998 with just $200 in her pocket and a lifetime of illusions. Patsy’s American Dream is the freedom to live her life as an openly queer woman, something that could and almost did get her killed as a teen in Jamaica. She is also following unrequited love to the United States, where Cicely, her childhood best friend and former secret lover, immigrated years ago. It's these two elements that move Patsy's story to a different place than many immigrant narratives: The economic opportunities Patsy might or might not have in America are largely beside the point. Her dreams of the United States center around an identity, not an income.

In fact, it’s Cicely’s letters that ultimately motivate Patsy to apply for one visa to the United States, which is declined, and then another. The letters — filled with descriptions of New York City streets and joy at the novelty of snow — are what keep Patsy going in the years between Cicely’s departure and her own — through a miscarriage, through the dogmatic judgements of her own mother, and through the birth of a daughter of whom Patsy is largely ambivalent. But Cicely’s letters, as readers quickly learn, have spun little more than fairy tales across the ocean, and she’s been forced to make sacrifices she’s told Patsy nothing about. Patsy’s first impression of New York City is of prolific pigeon waste. And almost immediately, the fairytale is over.

Like Dennis-Benn’s first novel, Here Comes The Sun, Patsy straddles the United States and Dennis-Benn’s own home of origin in Jamaica — the author immigrated to the United States herself when she was a teen. It alternates between the perspectives of Patsy and her daughter. As Patsy toils away for over a decade, undocumented, in the U.S. — first working as an underpaid bathroom attendant at a Jamaican restaurant, then as a house cleaner, then as a nanny — her daughter, Tru, experiences identity struggles parallel to those of Patsy, only a world away.

Ten years after Patsy left for the United States — and almost as many since Tru has had any contact from her — Tru is struggling to find a place for herself as a gender nonconforming soccer play who, up until recently, has only played with the boys. Once she starts menstruating, the expectations change. Suddenly she’s faced with the same judgement, threats, and fears that her mother experienced growing up in Jamaica herself. She is no longer the tiny five-year-old whom Patsy left behind, and the strain of a decade living with no explanation, no answers, and no contact from her mother begins to show.

While Patsy highlights the profound, and often unseen, sacrifices made in immigrants’ lives in America, it also emphasizes the struggles of those who are LGBTQIA+. “While people would pardon convicts, drunks, and men who fuck goats, cows, dogs, and children, they are suspicious, almost terrified, of a woman without a family and no religion. Jesus is the only viable excuse a young woman can use to deny the penis,” Dennis-Benn writes. In the end, Dennis-Benn touches upon the question of whether or not America is even still the promised land for all identities seeking freedom from persecution.

This article was originally published on