Books

This Haunting Poetry Collection Is An Essential Text About Hurricane Katrina

It has been 14 years since Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, and yet the total number of people who died in the storm and its aftermath is still unknown. Most estimates put the number of dead at around 1,800, but there is no memorial listing, no official way to remember and catalogue the people who lost their lives because the storm hit, the levees fails, and government officials failed to do what was necessary to protect them.

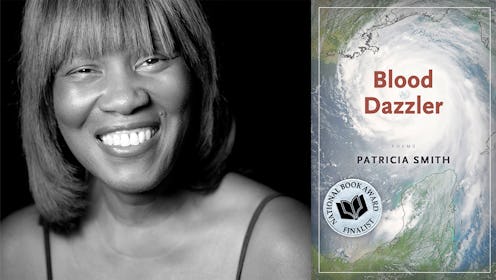

Patricia Smith, however, has found her own way to memorialize them: Poetry. In 2008, she released Blood Dazzler, a collection about New Orleans and the people of the city who were devastated by the storm. The collection, Smith's fifth, was finalist for the National Book Award and has since become an essential text about the tragedy.

In her minute-by-minute account of the storm, Smith weaves a tale of destruction, death, and despair that centers the humanity of those who were killed and those who survived. In the poem "34," about the 34 residents (the official count is now 35) of St. Rita's Nursing Home who died in the storm, she channels their voices in numbered sections:

"23.

Big Easy.

I ran your green,

rolled in your red dust,

and your sun turned the white of me red

and the black of me blue.

Funny how colored I got,

how I absorbed your heat, and how you,

without flinching,

called me your child."

Smith tells Bustle she wrote that poem before she had any designs of writing an entire collection about the storm. It was when she performed "34" on stage that she realized that some people didn't want to hear such a terrible and true story.

"Soon I realized that there was a faction of listeners who just didn't want to hear anything about Katrina," she tells Bustle in the Q&A below. "They wanted distraction, they didn't want to focus on tragedy anymore. I thought it was important that such a human and deeply tragic moment in our lives not disappear."

She knew she needed to tell the stories of those whose lives were destroyed by the storm, not as they were being told on the news, but as they deserved to be remembered. The result is a collection that is precise in its descriptions of the brutalities inflicted by nature and by mankind, and expansive in its empathy for those who were harmed, those who were killed, and those who were changed irrevocably by this tragedy.

In the interview below, Smith talks more about the process of writing this stunning collection, and why Hurricane Katrina is such a critical moment in U.S. history:

Bustle: The first thing that strikes me about this collection is the title: “Blood Dazzler.” The juxtaposition of those two words — blood and dazzle — seems quite at odds. Why did you feel “blood dazzler” was the perfect way to describe both the storm and your collection?

Patricia Smith: I'm horrible at titling both books and individual poems. When I got to the end of the poem "Siblings," I knew I needed something, something sonically and narratively perfect, something memorable for the reader to walk away with and hold on to. But I wanted to keep writing, and couldn't take the time to wait for that last line to descend. So I plucked the words "blood dazzler" out of the air as a placeholder, intended to come up with something later.

Meanwhile, I finished the book. When I went back to finish "Siblings," the words "blood dazzler" had grown to fit the poem — the phrase managed to meld beauty and suppressed violence, and was eerily undefinable. I never bothered giving it a definitive meaning. I'm not exactly sure why it worked, but it worked.

At what point in the creative process did you realize that Hurricane Katrina wasn’t a subject that could be contained to one poem — that an entire collection would be necessary to write about what happened?

I never intended to write a book about Katrina. I wrote the poem "34," about the nursing home residents left behind to die in St. Bernard Parish, because I felt a personal connection to that story. I had a relative suffering from Alzheimer's in that same sort of facility, with various members of our family assigned to participate in her care. I remembered a yellow button on the side of her bed that I could push whenever the situation got difficult — when my aunt didn't recognize me, refused to eat, grew belligerent. And someone would always come.

When I imagined the situation at St. Rita's in New Orleans — the lights out, water rising, no one answering the increasingly desperate calls from the residents — I could picture those types of buttons being pushed and pushed and pushed again. And no one coming.

I wrote the poem, which called forth the voices of the 34 gone, and began including it in readings. Soon I realized that there was a faction of listeners who just didn't want to hear anything about Katrina. They wanted distraction, they didn't want to focus on tragedy anymore. I thought it was important that such a human and deeply tragic moment in our lives not disappear. So other poems, which I guess were always there, began moving to the surface. Writing them was my attempt to keep the story alive long enough for more people to realize what it meant.

But I still wasn't thinking "book" or "collection." I was thinking "more and more of story."

"34" is a devastating poem — one that viscerally shows the destruction of this storm, and gives image to the humans impacted by it. Can you walk us through the creation of that poem and what you wanted to impart on its readers?

Along with what's mentioned above — I tried to wind back the clock and give each of the people who were lost a moment of their life back. In that moment, I didn't want them to be victims or tragic heroes. Instead I tried to stress their individuality, who they were beyond the way they died. I imagined a camera moving around the room, stopping briefly at each bed, bringing back just enough breath. I hope "34" is an example of what the persona poem can do.

Several of the poems are told in the voice of Hurricane Katrina. Why did you think her voice was important to include?

I've been writing in persona for years, so that perspective seemed a natural one to explore — and the stanzas really didn't really take on heat and motion until her voice emerged. It also provided a narrator and touchpoint for the chronicling of the storm's growth and destruction.

In an interview with New Mirage Journal in 2013, you said: “It helped to think of Katrina as a human story, not a regional one.” What were some of the literary techniques you used to ensure this collection felt like a human story?

Personification of the storm itself was one. And keeping the camera pulled in close — on people in the midst of crisis — was another. Keeping the lens tight meant writing about people and not weather — for example, the tiny glimpses of personality in "34." You can imagine Ethel in "Ethel's Sestina" dying the way she did in any environment, not necessarily the aftermath of a hurricane.

The poem "What To Tweak" juxtaposes your words with exact excerpts from the emails the only FEMA employee on the ground in New Orleans sent to his boss, Michael Brown, during the storm. The nonchalance of Brown's responses are infuriating. Can you talk about the ideation and creation of that poem, and when you decided you wanted to incorporate those words into the poem itself?

I didn't incorporate the words into the poem, I built the poem around the words. I wanted to take those dry, apathetic words and turn them upside down, shake them, pry them open to allow the lives affected to emerge. It was also important to infuse the poem with an energy, a drive and rhythm noticeably absent in Brown's emails. They weren't the only instance of "government speak" which threatened to turn Katrina into a faceless, voiceless "event."

Why is it so important that people continue to read Blood Dazzler and hold vigil and anger for the events of Hurricane Katrina?

It's not the hurricane — or the fire or tornado or any other natural disaster — that matters. We need to remain cognizant of just what our country is capable of — especially as it concerns people who aren't rich or white enough to matter in the eyes of those with power.

Blood Dazzler by Patricia Smith is available now.