Books

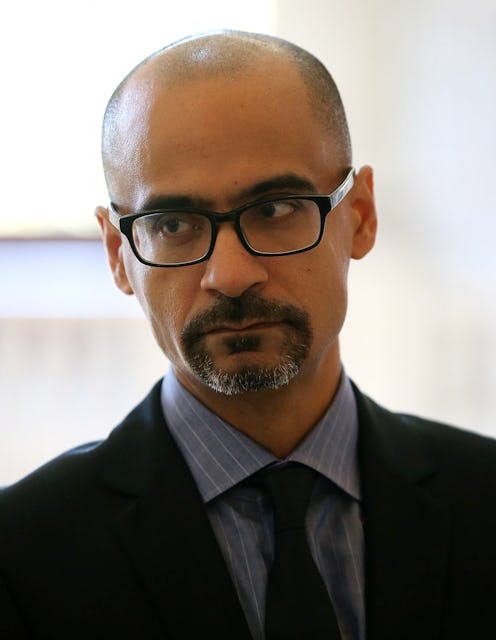

Junot Diaz Has Been Accused Of Sexual Harassment And Verbal Abuse By Multiple Women

In the midst of the book world's #MeToo reckoning and fresh on the heels of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature's postponement amid a sexual harassment scandal, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao author Junot Díaz has been accused of sexual misconduct. The initial allegation was made public on Twitter on May 4 when Zinzi Clemmons, author of What We Lose, came forward with her own story, a move that prompted several other writers to speak out against Díaz online.

Bustle reached out to both Clemmons and Díaz for comment.

UPDATE: In an email statement to Bustle, Clemmons wrote: "Junot Diaz has made his behavior the burden of young women — particularly women of color — for far too long, enabled by his team and the institutions that employ him. When this happened, I was a student; now I am a Professor and I cannot bear to think of the young women he has exploited in his position, and the many more that would be harmed if I said nothing. It is time for the burden of his bad behavior to be laid squarely at his feet, and for him to deal with the consequences of his actions. Not in a self-serving personal essay, but by losing some of what he has accumulated while conducting himself in this manner.”

Allegations of sexual misconduct against Díaz first appeared on Twitter late Thursday night when What We Lose author Zinzi Clemmons accused the Drown author of cornering her and forcibly kissing her. At the time, she says she was a 26-year-old graduate student, and she had invited Díaz to speak at a workshop about representation in literature. In her tweets, Clemmons also wrote that she was "far from the only one he's done this" to, and added that she "refused to be silent anymore."

In a follow-up tweet about the experience, Clemmons noted that, at the time, she told "several people" about her interaction with Díaz. She says she also has emails that Díaz sent her after the incident.

In the wake of her experience with Díaz, Clemmons said in a separate tweet, she has "avoided literary functions and posted no photos of myself online in order to avoid people like Díaz" and Lorin Stein, Paris Review editor who recently resigned from his post amid separate allegations of misconduct with women. "I'm sick of these talentless assholes dictating my life," the author wrote. "No more."

Clemmons is not the only person to accuse Díaz of mistreatment of women, both in his writing and in real life. Her Body and Other Parties author and National Book Award finalist Carmen Maria Machado took to Twitter on May 4 to share a story about an interaction she says she had with Díaz at a Q&A during his tour for This Is How You Lose Her. In a series of tweets, she described how the author responded to a question about Yunior, a character from This Is How You Lose Her: "He raised his voice, paced, implied I was a prude who didn't know how to read or draw reasonable conclusions from texts."

She went on to recount an encounter later during the same day in which Díaz referenced their earlier confrontation before reading the passages Machado had questioned him about.

Machado also used her Twitter thread to point out how particularly devastating Díaz's alleged misconduct is to people of color in the publishing community. "People of color are so underrepresented in publishing, we have deep attachments to those who succeed," she wrote. "People are defensive about JD because there are so few high-profile Latinx authors. I get it. That doesn’t change the facts.”

At the end of her Twitter thread, Machado summed things up by saying "Junot Díaz is a widely lauded, utterly beloved misogynist. His books are regressive and sexist. He has treated women horrifically in every way possible. And the #MeToo stories are just starting."

Bustle reached out to Machado for comment.

Machado and Clemmons were just the first of several writers and authors to speak out against Díaz's misconduct. After their tweets, writer Sinéad Gleeson said on Twitter that she had also had a tense interview with Díaz. Girl in the Road author Monica Byrne also came forward with allegations of "verbal sexual assault."

In the wake of the ongoing allegations against Díaz, many people have begun to speculate about the real motivation behind the author's New Yorker essay, which appeared in April. In the piece titled "The Silence: The Legacy of Childhood Trauma," Díaz described his own experience with childhood rape, and went into detail about the ways in which his sexual trauma has affected his adult life. "Classic trauma psychology: approach and retreat, approach and retreat," Díaz wrote. "And hurting other people in the process." Now, readers are speculating exactly what kind of "hurt" Díaz was alluding to.

To many, the piece that was originally called "heart-wrenching," "brave," and "moving" now appears to be a preemptive apology from the author for the allegations he might have known were coming. "I am not who I once was. I’m neither the brother who can’t touch a girl nor the asshole who sleeps around. I’m in therapy twice a week," he wrote in the piece. "I don’t drink (except in Japan, where I let myself have a beer). I don’t hurt people with my lies or my choices, and wherever I can I make amends; I take responsibility. I’ve come to learn that repair is never-ceasing."

Several writers and critics have now taken to Twitter to point out how, in the context of the mounting allegations from Clemmons, Machado, and others, Díaz's New Yorker piece reads as a confession or an attempt at damage control.

Critics have also expressed outrage over the allegations against Díaz for being what they say is just another example of the book community's ability to turn a blind eye to a powerful man's track record of behaving badly.

The allegations against Díaz come fresh on the heels of the cancellation of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature amid sexual abuse scandal, and in the wake of several other powerful men in the literary world being taken down by the #MeToo reckoning. It has left many book-lovers wondering how to react.

What happens next, no one can say for sure, but one thing is becoming clearer than ever: the literary world has a problem with its treatment of women, and it's one that needs to be addressed immediately.