Books

This New Book About The Life Of "Ordinary Women" Is STUNNING

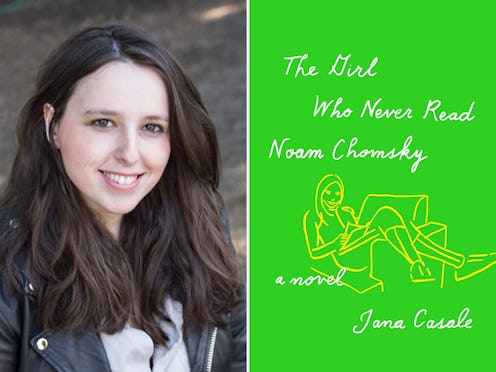

My bookshelves are filled with women: women writers and women’s stories; women who look and live and love like me, and women who don’t; fictional women and real women and women who fall somewhere in between. My bookshelves have always looked like this — the privilege of being born in a particular type of body, at a particular time in history, in an artistically free society being that I’ve not often experienced that gap between the stories I want to read and the stories available to me, which women of other bodies, generations, and cultures have always been subject to. It’s a privilege so prevalent throughout my book-loving life that sometimes I’m guilty of forgetting it’s a privilege at all; that everyone doesn’t feel as well-represented by their bookshelves as I do by mine. At least, that is, until I read a novel like Jana Casale’s debut, The Girl Who Never Read Noam Chomsky.

Out now from Knopf, The Girl Who Never Read Noam Chomsky tells the story of Leda, who we meet at college, in Boston. “At this point in her life she had a stack of books she kept by the bed and a splinter in her right hand. She should have thought more closely about cleaning out her microwave,” Casale writes. Readers follow Leda as she worries over her body, joins a gym and then cancels her membership days later, grows melancholy over having no one in her life to talk about light fixtures with, flirts and flounders, languishes in undergraduate writing workshops, worries over her body some more, buys an over-priced copy of Noam Chomsky’s Problems of Knowledge and Freedom with some vague notion of impressing a boy in a coffee shop who she’ll never see again, and then never, ever reads it. (Her daughter will find it decades later, while sorting through her mother’s things after Leda’s death, and toss it into a donation box.)

The Girl Who Never Read Noam Chomsky by Jana Casale, $28, Amazon

From that teenaged moment of deciding to read Noam Chomsky to Leda's death, readers bear witness to beautifully rendered but seemingly insignificant moments that, somehow, make up an entire life. That is, in essence, the question that lies at the center of Casale’s debut: what makes up a life? More specifically: what makes up a woman’s life? An ordinary woman’s life? And perhaps, most importantly, what happens when someone not only dares to write, but then to publish, an entire novel about the entire lifetime of one such woman? Does, as Muriel Rukeyser suggested, the world in fact split open?

It’s a torch first lit by writers like Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, and Kate Chopin; one taken up by those like Elena Ferrante, Zadie Smith, Rona Jaffe, Maggie Shipstead, and most recently (and to great world-splitting) Kristen Roupenian — women writers who look closely at the experience of ordinary womanhood, and deem it worthy of great literature.

But what is an “ordinary woman”?

Is she Ifemelu in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah — a Nigerian immigrant living in the United States, who blogs about race and her life and has a fellowship at Princeton and frequents hair salons? Is she the characters who populate Alison Bechdel’s comic strips — funny and frank and loving, navigating the last three decades of queer life in America? Is she Lila Cerullo and Elena Greco, the two women whose friendship is immortalized in Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan Novels — who spend 50 years of their complicated and ordinary and restless and beautiful lives being young and growing old, being mothered and mothering, doing little to set themselves apart from the millions of “ordinary women” who did and do the same, aside from being themselves?

Maybe the “ordinary woman” is Shelia Heti’s divorced woman (also named Shelia) in How Should A Person Be? — a mess of contradictions, who works at a beauty salon, writes for a feminist theater, and second-guesses her every action based on the actions of those around her. Maybe she’s Jenny Offill’s ambitions artist, halted by marriage and new motherhood, whose baby is soothed by the fluorescent lighting of Rite Aid. Or perhaps she’s Virginia Woolf’s women — domestic, modestly upper-class elite, who maintain their homes and throw their parties and, if they ever do have sex, certainly don’t do so in the pages of their novels.

Maybe she’s Jane Bennet, or Jane Eyre, or Janie Crawford, or Tita de la Garza; Meg March, or Molly Weasley, or Robin Stokes, or Bridget Jones. Quite possibly, she’s Margot from ‘Cat Person’.

Or maybe she’s all of them, and more.

The burden of writing literature of “ordinary women” is that, too often, books about women are books about HOW to be women — instructional manuals or cautionary tales disguised as fiction, demonstrating how women do and do not, should and should not, live in the world. When it comes to women in literature “ordinary” becomes synonymous with “unremarkable” — and if you’re unremarkable, you must not be causing too much trouble. If you’re not causing too much trouble you must have subscribed, at least in part, to the blueprint contemporary society has laid out for you. The consequence, then, is that your story is not worth telling.

Casale’s protagonist doesn’t fall into this trap. Sure, she's exposed to many of the feminine prerequisites many women do, for better or worse: She’s often eager to please others, if for no other reason than to avoid the hassle of displeasing them. Most of her sexual encounters are based on the fact that she is more turned on by the idea of herself as a turn on, rather than by the person she’s with. She notes the inordinate amount of energy women spend trying to avoid being raped.

When Leda attends a college party, early in the novel, Casale writes:

"She hated beer, but it was preferable to standing there with a soda, having to explain why she wasn’t drinking. She’d grow accustomed to drinking intolerable drinks at parties by holding her breath and taking small sips. Once, a doctor asked her if she drank. 'Socially,' Leda said. 'What does ‘socially’ mean? I always wonder,' the doctor asked. 'It means that you drink enough so that no one asks you why you aren’t drinking.'"

Later, when her future husband mentions he doesn’t like the aesthetic of shaved pubic hair Leda thinks:

“It didn’t matter that he didn’t like it, or that she didn’t like it, she just felt like she had to do it… It ran in her mind like little clicks of things she had to do. Eat. Drink. Shave your vagina.”

She spends that miserably obligatory year away from home (California.) She struggles with the frustrating impulse to get engaged. She’s knocked completely off guard by the sudden chiming of her biological clock. She grows weary of the Mommy Wars. She’s discouraged by the ways women antagonize one another on social media. Her career gets away from her. Her daughter’s school play becomes the most important thing in her day.

But readers never get the sense that Leda is holding up her life as instruction. Nor, as a cautionary tale. Rather, she’s holding it up as a life worthy of living, worthy of literature. She’s funny and sad, observant and honest, tender and imperfect, complicated and relatable. And that is enough.

Time, for Leda, begins familiarly, agonizingly slow — every decision is monumental, every turned corner is the one that will either reveal her fate or demolish her destiny. Then, somewhere along the way, the years begin to fly by. An identity is realized. A life is made. Some things are inevitable and others never come to fruition. Leda has her baby but never writes her book. She outlives her husband. She never reads Noam Chomsky. And that is enough too.