Books

In This New Book, A "Farm" For Surrogate Mothers Hides Dark Truths

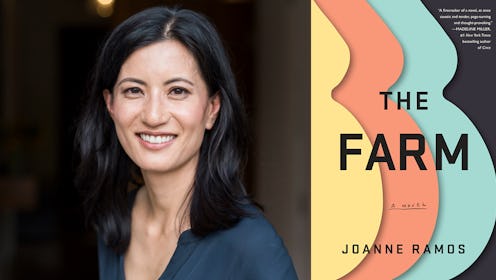

When author Joanne Ramos began writing her debut novel, The Farm, she hadn’t written fiction in 20 years. "I think as an immigrant it just wasn’t in my worldview that I could make a living by making up stories,” Ramos tells Bustle. "It didn’t seem practical with college debt, and then life just took me in a different direction. But the ideas behind The Farm have really been with me really for most of my life."

The Farm transports readers to a hidden corner of the Hudson Valley, where a facility called Golden Oaks boasts the kinds of amenities one would expect in a luxury spa. The center is actually a top-secret, in-demand home for surrogate mothers. They’re called “Hosts,” and their job is to carry the babies of the global elite who cannot or choose not to carry their own children.

The Hosts at Golden Oaks, however, are not your average surrogates. Everything from their daily step counts to their meals to their online browser histories is monitored with exacting diligence. They receive daily massage treatments, private fitness training, in-utero sound therapy and more — anything to “jumpstart” the babies in their wombs, ensuring they are born already leaps and bounds ahead of their peers. For their efforts, Hosts receive the kind of paycheck that could be life-changing. The only catch? These women — many of them Filipino immigrants and mothers themselves — must leave their entire lives behind for nine months. They cannot leave the grounds of Golden Oaks, and their own families cannot come to them. Most of them, like Ramos’s main character Jane, can’t even tell their families where they really are.

Much of the inspiration for The Farm came from Ramos’s own life, though perhaps not in the way readers might expect. A Filipino immigrant herself, Ramos attended Princeton before starting a career in high finance, becoming a mother, immersing herself in the world of full-time Manhattanite moms, then returning to the workforce. She has spent her entire life straddling worlds.

"Everyone always thought we were from the same family because there weren’t any other people who looked like us.”

Ramos’s family immigrated from the Philippines to Racine, Wisconsin in the late 1970s when she was six years old. She describes it as a hard time for the Midwest; the auto manufacturing industry was shutting down, and it was a different place than now in terms of ethnic and cultural diversity. "We were one of the few Asian families in our town," says Ramos. "It was just me and my little sister, and two Asian brothers in our big public elementary school. Everyone always thought we were from the same family because there weren’t any other people who looked like us."

But on the weekends, the author explains, she visited her dad’s family in Milwaukee, where there was a small but tight-knit Filipino community. She describes the difference between her weekdays in Racine and her weekends in Milwaukee: the gossiping Aunties and Uncles, the Filipino doctors she met, the spectrum of immigrants — some documented, others not. After Princeton, Ramos began a career on Wall Street, where she was one of the few women at Morgan Stanley and the only female investor at a private equity shop.

"They were great guys," Ramos says of her colleagues, "but all I wanted to do was fit in. I wanted to be one of the boys. Laughing off jokes because I wanted to be the cool girl. Taking a third shot of flaming Sambuca to show that I could hang. All of that stuff — which was very normal to me back then because that’s what you did, you wanted to be the cool chick, the one who fit in, who didn’t rock the boat — all of that stuff made its way into the book without me even realizing it."

The Wall Street dynamics Ramos speaks of make their way into her novel through the character of Mae Yu, the manager of Golden Oaks and the woman who conceived of the facility in the first place. A complicated character, Mae Yu is a woman who manipulates people, but that manipulation arises because it is the only way she has been able to succeed in the all-male world she lives and works in. In The Farm, Mae reflects on how the idea for Golden Oaks came to be, saying: “If women could outsource their pregnancies, they’d be the ones running the show.” From Mae’s initial perspective, Golden Oaks began as a way to liberate women, but the liberation of some comes at the relative subjugation of others.

When Ramos started a family in Lower Manhattan, the culture of perfect parenting hit her full-force. The characters in The Farm — whether they’re Filipino immigrants forced to leave their own children for months or years at a time just to make a living, or billionaires outsourcing their gestation in order to give their babies every advantage from the moment of conception — all want the best for their children. And sometimes, that "best" comes at great expense.

"With money and privilege that idea can go crazy places unless you’re very clear to yourself on what it means to give your kids 'the best.'"

"First of all, I don’t believe that kids need the best: the best school, the best student center at the school. I don’t even know anymore what that — ‘the best’ — means, fundamentally," says Ramos. "With money and privilege that idea can go crazy places unless you’re very clear to yourself on what it means to give your kids ‘the best.’ I’ve thought about that a lot as a parent and as someone whose kids have a lot more — at least economically — than I myself did growing up: What do I mean by the best? What am I trying to give my kids? Is it this rush to give them an edge, the so-called best? That, in a lot of ways, led to writing the world of Golden Oaks. These are people with all the means in the world, and they just want to give their kids an edge in utero. It’s fictionalized, but it’s an absolute extension of what we’re seeing now.”

Ramos also noticed something else during her years as a full-time mother: the only Filipinos she encountered in her day-to-day life in Manhattan were domestic workers. "As a mother myself I would imagine: What does it feel like to take care of other people’s children all day if you’re a mother yourself? What is it like for a mother who can’t give her own kids 'the best' of everything, but is employed helping other people give their kids the best?"

"These are sacrifices made by people who maybe don’t have access to all the best options. In many ways, they are sacrifices made for family, at the sacrifice of family."

She adds, "I would hear stories about baby nurses who hadn’t seen their kids in decades because they were back home in the Philippines. Or mothers whose kids were [in the United States] with them but who didn’t get to see them because they worked a day job and a night job. These are sacrifices made by people who maybe don’t have access to all the best options. In many ways, they are sacrifices made for family, at the sacrifice of family."

Ramos’s character Jane is one such mother; she leaves her own daughter, Amalia, to become a surrogate at The Farm when Amalia is just six-months-old. It is a heart-wrenching decision, one that drives Jane nearly crazy throughout her time in surrogacy. Similarly, the woman Jane is forced to leave Amalia with, a fellow Filipino immigrant named Ate, hasn’t seen her own children in years. She has been sending money home to them in the Philippines since they were teens.

"I do think in some ways the American Dream exists still; but does it work less and if so why? And are we okay with that?"

The emotional costs to these women are immeasurable. It is, as Ramos describes, a significant sacrifice for family, at a significant sacrifice to family. These are all-too-real circumstances designed to leave readers wondering about the weight of responsibility mothers carry, about what it means to do the best for your children, and about the immense expectations placed on mothers.

"I think the base compulsion is a good one: I just love my kid," Ramos says. "Some women in the book have the means to give so much, and some women don’t have very many options at all. I want to leave my readers questioning whether or not they think things will change for Jane and Amalia, if they think that gulf [between privilege and poverty] is bridgeable anymore — to think about the American Dream and whether or not it’s broken, or if it ever even really worked. I do think in some ways the American Dream exists still; but does it work less and if so why? And are we okay with that? And if we are okay with that, then let's carry on. But if we’re not, then why not, and what are we going to do about it?"

This article was originally published on