Books

What Happens When You Purposely Don't Have Friends — But Decide You Want To Change That?

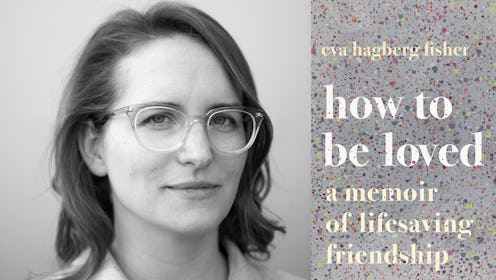

Eva Hagberg will tell you she has at least 10 best friends, but her life wasn’t always so rich. In her debut memoir, How to be Loved, the author writes of how — despite her belief that she was “fundamentally wired to be alone” — friends helped her survive not one, but two catastrophic illnesses that occurred almost back-to-back.

There are studies that back Hagberg’s claim that the friendships she made over the course of her two illnesses — a brain mass and mysterious immune deterioration — were healing. While Hagberg acknowledges that it took a traumatic illness for her to abandon her lone wolf persona, the journey doesn’t need to be nearly so dramatic for anyone else looking to expand intimacy in their own life.

"Look, everyone is dealing with something that is catastrophic to them all the time," Hagberg tells Bustle. "Comparing your suffering to someone else’s isn’t useful; there’s no objective ladder of suffering."

What’s more important, she believes, is to respect yourself enough to want to make changes. Hagberg writes that she got to a point of asking herself, “Would I rather suffer?”

How to be Loved is not a self-help book, yet it offers clear examples of how Hagberg cultivated close friendships after a lifetime of being alone. In 2013, when she was 30-years-old, doctors discovered a cyst on her brain. It was a life-altering moment, and it forced her to recognize that her life lacked intimacy. It was then she began inviting more friendship into her life in three distinct ways.

"Comparing your suffering to someone else’s isn’t useful; there’s no objective ladder of suffering."

First, she allowed herself to be more unguarded. "We cannot be intimate when we are not vulnerable," Hagberg says. She learned to ask people, "Can you help me figure this out?"

As part of this first step, she learned how to move forward with people based on how their conversations go. "There are some people I can’t bring things to," she says. That’s why she has so many best friends now. "Everyone brings a different perspective."

This differs from the way she previously approached people. In the book, she writes of how she used to enter a room "to scan and assess: looking first for a boy I could get into some trouble with and then a girl I could maybe also get into some trouble with, and then for who seemed to be in charge, and who wasn’t." She was always trying to put people in a certain box.

This openness solidified in Hagberg’s second phase of deepening friendships. This involved becoming more honest with herself and others, a shift she credits to a woman named Allison, whom she met before she first got sick. Allison was terminally ill with cancer, and Hagberg tried — and failed — to pigeonhole her into one of her friend zones. ("Was she a wise sick sage?" Hagberg asks in the book.) At first, she mostly saw Allison out of social obligation. But over time, she tells readers, something about Allison made "a tightness in [her] chest [uncoil], just a millimeter." She found herself confessing her fears to Allison, without predicting where their interactions might go.

That’s why she has so many best friends now. "Everyone brings a different perspective."

"I had never been touched or held with a kind of pure and untrammeled love before,” Hagberg writes. “[A] love that... didn’t request anything of me."

The final step was setting boundaries, emotionally and physically. Because of her immune disease, she had to get comfortable asking people not to hug her. “Being able to set those boundaries around my body,” she writes, “is part of what let me open them up again.”

Despite the gains — and friends — she has made, Hagberg admits she still grapples with the feeling that she is inherently unlovable. "From childhood I was taught that my value came from what I did, how well I performed," she says. "It’s a capitalist view of society. We are measured by what we produce. And it’s very hard to turn that boat." In response, she became somewhat of an overachiever. Even during her illnesses, Hagberg earned a master’s in architecture, and then a Ph.D. in Visual and Narrative Culture. She was also in alcohol addiction recovery.

"I’ve coped with my pain in so many ways that are 'bad,'" she says, laughing. "I had no choice but to learn to be compassionate toward myself, then I could offer that to others."

This article was originally published on