Life

I’m Tired Of Black History Being Whitewashed

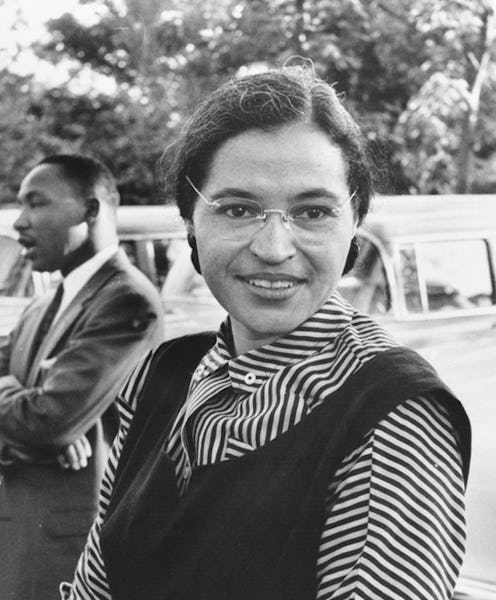

Black History Month is a crucial time for reflecting on the ways Black Americans have contributed to American society. It’s also an important time to tell more stories about all of the prejudices Black Americans have faced throughout the decades that have long been erased from history books — not just the popular narratives most people know about, like Rosa Parks' refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger because she was "tired" (spoiler alert: she was, in fact, a capital-A Activist). I'm tired of Black History being whitewashed, revised, and erased — and as Black History Month winds down, it's an important time to look at why this happens, and how we can prevent it from happening going forward.

Throughout my adolescence, my American history courses often treated the experiences of Black Americans like a minor part of the American origin story and its trajectory into becoming a major international power. Our lessons on the Civil Rights Era in particular were formulaic, only ever discussing a handful of historical figures involved in the movement. By the time I reached my senior year of high school, I knew exactly what people my teachers would focus their attention on: Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Thurgood Marshall — maybe Malcolm X, if the teacher was a bit daring. It wasn’t until college did I learn about influential but unsung figures like Bayard Rustin, the chief organizer of the monumental March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Like so many other critical voices in the fight for racial justice, Bayard remains largely unknown to most Americans because he never fit the bill of a respectable leader (he was openly gay during an era where LGBTQ issues were not mainstream, according his New York Times obituary.)

You could argue that my experience with American history classes were so meager because I went to public school, but that wouldn’t tell the whole story. Across the nation, schoolchildren aren’t being taught the complete, nuanced stories about the severities black Americans have experienced since this country’s founding. A recent report by the Southern Poverty Law Center, “Teaching the Hard History of American Slavery,” highlights just how deeply miseducated American students are about the brutalities of chattel slavery, to such a degree that they don’t know that it was the primary driver of the Civil War — one of the most important periods of American history. A mere 8 percent of the high school seniors who were surveyed properly identified slavery as the central reason for the war, and fewer than half correctly answered that slavery was legal in all colonies during the American Revolution.

While these finds are alarming, they are also not all surprising. We do, after all, have an education system in America that rewards student’s abilities to regurgitate information they’re told in order to pass standardized tests — even if what they are taught is factually incorrect. It also speaks to how much the stories we’re told are twisted to to fit a certain political narrative. Unless students are lucky enough to get a history teacher who isn’t afraid to use their own set of teaching methods outside of the assigned textbooks students have grown accustomed to, students will never fully understand the rich, but harrowing nature of American history.

There’s also the problem by which American history, and especially Black history, is commonly taught. Overwhelmingly, it’s told as a series of accomplishments and advancements throughout time made by a select few — usually older white men — without any political or social setbacks or consequences. Lessons often go from one major historical moment to the next without accounting for the impact certain policies had on the lives of citizens, particularly the marginalized. And rarely, if ever, are connections drawn between the past and present. For example, my teachers never once mentioned that immediately after the Civil Rights Movement came the War on Drugs, a set of government initiatives instituted by president Ronald Reagan that devastated communities of color because of racially motivated drug laws such as mandatory minimums. Just as I learned about Bayard Rustin, I found out about this federal campaign and its effects on people of color during college. That oversight limited my knowledge about race relations for so many years, and my understanding of why the fight for racial equality is far from over.

Another common issue with how Black history is taught is how the legacies of popular historical figures like Martin Luther King. Jr. are (mis)remembered in our public consciousness. Over the past couple of years, I’ve heard a number of conservative pundits proclaim that if Dr. King were alive, he would detest the current Black Lives Matter movement, or that he actually a conservative at heart. Such remarks literally whitewash how radical Dr. King’s ideas and political stances were to many people at the time, and how similar they are to the current fight for racial justice. By the time he was assassinated, most Americans distrusted him and the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. According to a Gallup poll from 1964, the same year the landmark Civil Rights Act was passed, 43% of respondents viewed Dr. King positively, while 39% answered negatively. By 1965, the responses were split evenly, and in 1966, the were overwhelming negative. Even after the Civil Rights Act was signed into law, leveling the playing field for all Americans, Black people, especially those with public profiles like MLK Jr. still weren’t viewed favorably by a lot of people. It took several decades before a major shift in the public’s perception of Black Americans.

If my experience with school has taught me anything, it’s that the consistent erasure of certain historical figures and the whitewashing of American history is a serious issue in education. Teachers need to do a better job at educating students on a wider breadth of narratives about Black History and how they tie into the larger American story. If Americans plan on creating a more equitable society that recognizes the rights of everyone no matter their background, we need to have more open discussions about our past failings in history, in addition to celebrating our successes, so we can have a better understanding of where we need to go.