Life

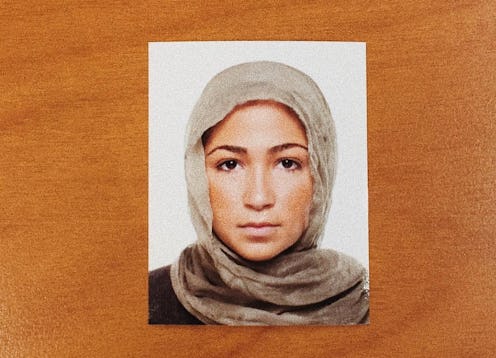

I Was Told To Stop Racially Identifying As "Other" On Applications — Here’s Why I Won’t Listen

This year, Bustle is celebrating Rule Breakers — the women and non-binary individuals among us who dare to be themselves no matter what. In the lead-up to our list of Bustle's Rule Breakers of 2018 going live in late August, we are featuring stories from an array of individuals about critical moments when they didn't do as they were told. In a world that encourages us to conform unquestioningly, they refused to look or act the part, and we're all better for it. Click here to buy tickets for the event.

A circle is more than just a shape — it's a larger symbol for protection, inclusion, and wholeness. And yet, it's this very formation that routinely leads me to reconcile my own alienation in America. These circles linger around every big life event and mundane annual checkpoint. They mock me at the doctors' office, sneered as I filled out my college applications, and give me the cold shoulder during each job interview.

What is your race? Mark X for one or more circles below.

There's one big problem with this query: my cultural identity, and thus, my racial recognition, doesn't fit within the boundaries of a box, much less a circle. I am an Iranian-American dual citizen. Both of my parents, and their parents before them, were born and raised in Iran. And while I grew up in New York City, I have always been hyperaware of my cultural identity, and the ways in which it set me apart from those around me. I was lucky enough to have been raised in a fruitful Persian community — speaking and practicing Farsi, preparing and sharing family recipes, and celebrating traditional holidays. And yet, my entire life I have defined myself by what I am not, instead of what I am. I exist in the negative.

There have always been physical differences defined by my Persian heritage that I felt were perceived as flaws. They led my peers to gawk mercilessly, exposing their divisive nature. My skin tone was darker, and I possessed an incredible amount of hair, well, everywhere: my face, my arms, my legs. In the world of Manhattan prep schools, I was an anomaly. And yet, I was routinely reminded by my family members that I was technically white. How could that possibly be? I always wondered. I pushed back against this notion from an early age, as I was constantly prompted by middle school bullies to recall that I was far from white. They teased and taunted my "other-ness" until I had internalized their comments as self-hatred. Thus, the evidence of my ethnicity appeared rather contradictory. I remained confused and misguided.

It wasn't just my parents. In North America, Iranians are currently instructed to identify as "white" on records, by the census bureau. This is because Persians consider their roots to be derived from a branch of Indo-Europeans, who called themselves the Aryan Shahr, meaning the "Aryan Realm". In fact, Persia retained its name until the 30s, when Reza Shah, influenced by Germany, decided to officially change its name to Iran — which literally translates to 'Land of the Ayrans'.

However, while the origins of the caucuses were indeed thought to be white, through conquest of other peoples such as the Elamites, the Persian people gradually became "browner". Iran is now a multiethnic nation of Persians, Azeri Turks, Kurds, Baluchis, Arabs, Armenians, and many other groups that, through imperial conquest, became distinctly Iranian. So while many Iranians continue to identify as Aryans, Aryan does not mean white. It's solely a method of identifying that we originated from the Indo-European race.

"Personally, even thinking of identifying as a white feels like a deceitful lie, not a safety net."

The truth is, this "Aryan Myth" that Persians pass down through generations is rooted in racial bias and inequality. Although shameful, many Iranians were taught from an early age to pride themselves for their Aryan blood and to look down on Arabs and Turks. Some of those who immigrated to the West during the revolution hid behind this racist ideology, believing that by masking their "brown-ness" and identifying as, and passing for, white, they were marking themselves as the "safe kind" of Middle Eastern transplant.

But it soon became clear that identifying as white would not be a safeguard against discrimination and xenophobia. The fear and hatred of Iranian-Americans can be traced back to the Iranian Hostage crisis of 1979, when anti-Iran protests were being held throughout America. Tensions increased post 9/11, when the Patriot Act subconsciously and overtly pushed Americans to view those who had immigrated from the Middle East as a threat. And yet, throughout this period — from the Axis of Evil, to Trump's numerous travel bans and recent decision to pull out of the Iran Nuclear Deal — all the while, Iranian-American citizens have continued identifying as white, even though they are viewed by the rest of society as anything but.

There was even a movement that led up to the 2010 national census called "Check it right, You Ain't White" that urged Iranian Americans to stand up and be counted. This petition targeted Arabs and Iranian-Americans, encouraging them to write in their ethnic identification instead of checking white. Unfortunately, the phenomenon failed, with the majority of Iranian Americans choosing not to participate in the census at all. Why? A few of my family members cited fear: the paranoia that labeling themselves as anything but white, let alone Middle Eastern, could one day come back to haunt them. Identifying as white continues to be seen as a security blanket, a means to protect one's self from racial bias, discrimination, and perhaps persecution, during an age of rampant Islamaphobic rhetoric and rising tensions — but it is no longer enough.

There's an engrained ideology lingering in the minds of many American minorities that passing for white might be able 'save us', or at the very least, protect us from strains of racial bias and being discriminated against. And there's some merit to that belief: a 2015 study by Villanova University discovered that white interviewers deemed lighter-skinned black and Hispanic people to be more intelligent than darker-skinned people who had "identical educational achievement, vocabularies, scores on a political test, and a variety of other factors." But as the level of hostility continues to escalate between my two nations, my identity is only becoming more and more ambiguous to those around me. Personally, even thinking of identifying as a white feels like a deceitful lie, not a safety net.

"We are not seen, nor treated, as white Americans, no matter what claimed history we attempt to hide behind, or box we choose to shade in."

As a child, I was mocked endlessly by boys on AIM, who called me by terrorist names without a second thought. Growing up in a post 9/11 New York, I was often asked by my peers if I was "taking a side", despite Iraq and Iran being two entirely different nations. When I travel to certain parts of the United States, I am met with glares of disgust and slurs muttered under people's breath. I feel unsettled when writing my name down on everything from applications, to restaurant reservation forms, because of my tried and true knowledge of the inadvertent bias it's met with. I have to be cognizant of when and where I speak my beautiful native language, because of the fear I've fostered of drawing negative attention to myself. The President of the United States has routinely attempted to ban my family members from entering this country.

These are not the collective of experiences of someone benefiting from white privilege. Does that mean that I am not privileged in other ways? Of course not. But these incidents are a bi-product of my racial identity contextualized by our global landscape, plain and simple. These are the realities of being Middle Eastern in today's America, of survival in this socio-political climate. We are not seen, nor treated, as white Americans, no matter what claimed history we attempt to hide behind, or box we choose to shade in.

So, I break the rules. I check "other". I embrace being undefined. My ethnic identity, my racial experience, my torn cultural selfhood simply does not fit within a circle. It’s a much larger vignette, which reflects a confusing slew of politics, privilege, and oppression. I am proud to be both Iranian and American, so until there's a circle that encompasses both, and allows me to take ownership of both facets of my identity, I'll keep selecting the box less checked.